![]()

Part I

Preamble

The heart and the CIAM’s discourse

![]()

Introduction

The heart and the city

HERE IS…

A new book about people

And the space around them

And how the space has been filled…

And you – the architect, designer, city planner – are also trying to make the city the best possible to live in, which is why you will want to read this book.1

Russell F. Neale, Introduction to The Heart of the City, Pellegrini and Cudahy edition, 1952

This book is centred on the complex and ambiguous relationship between an abstract organic metaphor and its interpretative use and influence on the corporeal urban structure: the Heart of the City.

This encounter between the city and the heart, the “palpable and [the] verbal, [the] ‘objectal’ and [the] semantic”2 is a spirally recurrent topic in the history of urbanism and still affects our contemporary urban and social condition. The strong association between the city and the human body is archetypical and it is so insightful that in antiquity the secret and inaccessible structure of the body was interpreted and understood through the structure of the city rather than the contrary: “the human body was as a city,”3 as the urbanist Bernardo Secchi remembered. Hence, also the heart of the City can be assumed as one of the “certain continuous things running through history,”4 as an archetypical idea of public space, a preconscious a priori, universally recognised or even “the eternal present.”5

As far as our condition is concerned, the image of the heart remains a contemporary “central organ of internalized humanity in the dominant language games of our civilization,”6 thanks to its “capacity for relationships – in all places at all times” according to the well-known philosopher Peter Sloterdijk.

Consequently, when attributed to the city, the heart refers to the innermost essence of its public life, to the identity and rights of the public realm, to the proper balance between the private and the public, to the ideal conjunction between the social and physical structure of the city, which are still important, unresolved contemporary issues: “We shall start out from the one point accessible to us, the one eternal center of all things.” – Jacob Burckhardt claimed as early as 1868, and Giedion recalled in his discourse about the Heart in the 1950s – “We shall study the recurrent, constant, and typical as echoing in us and intelligible through us.”7

The Heart of the City is certainly part of this intangible echo, becoming of paramount importance in the face of the fear of the vanishing city, or its legibility, and the dissolution of the contemporary urban elements, as described by Secchi who radically highlighted the contemporary need to go back and study the socio-spatial “elements which lie at the foundations of the urban structure.”8 The Heart of the City is certainly one of them; it is a Constituent Element at the base of the urban structure. Christopher Alexander recently described it as “positive space”9 or “necessary binding force that creates the core of every city”10 and its social-spatial relationships.

With reference to these topics, the book critically illustrates the continuity and the complexity of the theme of the Heart of the City, as a multifaceted social and spatial category which lies at the crossroads of the intellectual-theoretical and architectural-design worlds. The aim of the book is to unearth the different levels of significance of the Heart of the City, historically and theoretically analysing its concepts within the post-war architectural debate, and to detect the links and brand new perspectives on the significance of public space in our contemporary urban condition. As Michel Foucault stated when describing his idea of the “history of the present”:

The game is to try to detect those things which have not yet been talked about, those things that, at the present time, introduce, show, give some more or less vague indications of the fragility of our system of thought, in our way of reflecting, in our practices.11

Today’s urgency to tackle our contemporary political, social fragility of system of thought through “Elementarism”12 and the constituent elements of the public sphere, through the “Fundamentals”13 of our practice and everyday life embraces the ambition of this book about the Heart of the City.

This is clear if we really look back at and analyse the issues relating to the formation of our modern structure of society and the city in the post-war period and consider the topic of the Heart as the “question of the reform of the structure of the city,” through “the creation of centres of social life”14 as Le Corbusier had already proposed it under the elitist umbrella of CIAM – “Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne,” in 1951.

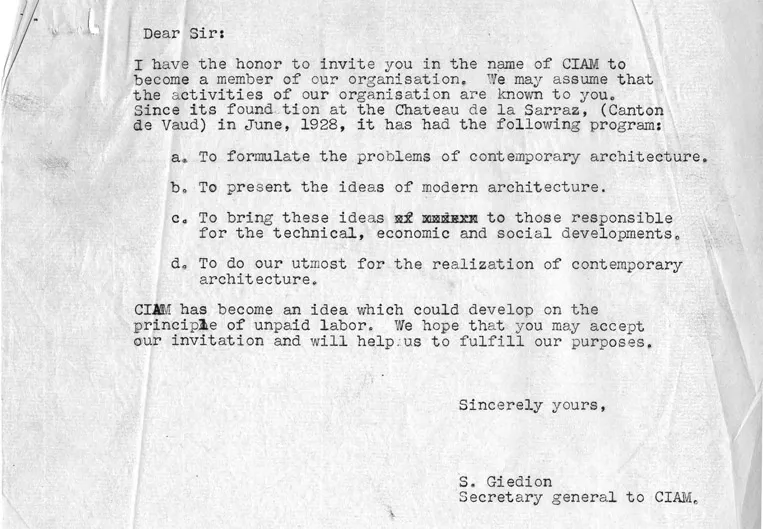

From CIAM to CIAM 8

CIAM was the most institutional, highly cultural and exclusive group of the last century. In the 1960s, Banham defined it “the official Establishment of architecture in our time.”15 Founded in 1928 in the castle of Mme Hélène de Mandrot in La Sarraz, CIAM was officially disrupted in 1959 in Otterlo by the progressive ideas of a younger generation of architects who had been raised in its womb and were later called the Team 10. In its thirty-year life, CIAM had certainly played a pivotal role in framing and contaminating architectural-urban thinking worldwide. Within the CIAM, the “C” standing for “Congress” was first used and selected for its original sense of collaboration, of “marching together”16 as described by the Swiss historian Sigfried Giedion. It soon shifted into a trench17 of avant-garde, as “the basis of a new architecture”18 which was destined to influence both the theoretical debate on the city and its physical, corporeal configuration up until the present day.

In particular, CIAM’s last period of life coincided with the base for worldwide theoretical and urban design activity of the last sixty years. Therefore, studying the last CIAM movement means studying our nearest origins and their current influence on our profession. This thesis is supported by Vittorio Gregotti who, as pupil of the Italian CIAM member Ernesto Nathan Rogers, stressed that the post-war CIAM has transmitted the essence of the Modern, offering the basic work materials for the younger generations, which are still working and sharing their values and criticisms.19

Figure I.1 CIAM, Invitation Letter to New CIAM Members.

As far as the CIAM 8 is concerned, the years after the Second World War coincided within CIAM with a passage from orthodox functionalism to open humanism, from the abstract machine-age interpretations to other “regional variation, history, and politics as well as socio-economic and anthropological interpretations”20 (Grahame Shane). This critical passage was already evident in 1951 during the CIAM 8: the debate on the contradictory and pervasive figure of speech of the Heart traced the shift from the analytical, “universalist and exclusive approach”21 (Pedret) of both theoretical and urban compartmentalisation of the orthodox pre-war CIAM to a comprehensive synthetic idea of anthropological habitat.22 Indeed the Heart became part of the new humanism and existentialism, as already highlighted by de Solà-Morales and Curtis.23 It even “represented the collapse of Modern Architecture”24 according to Grahame Shane, becoming a counterforce to the zoning method of planning, of the division into four functions (dwelling, work, recreation and transport) of the Charter of Athens, to the rational development methods of “The Functional City” of the 1930s which emphasised and mythologised the heroic first decades of CIAM. CIAM’s discourse on the Heart also became the “precursor”25 of the later discourse on Urban Design in the US and it activated an “epistemological shift towards the ordinary everyday life”26 which became central in the notion of habitat as later discussed by Team 10.

Therefore, CIAM 8 embodied a deep complexity of values and significance that can be hardly compressed within the mere issue of post-war reconstruction, as generally – and erroneously – thought.27 The same issue of reconstruction enhanced different arguments about the commercial, political, sculptural and symbolical aspect of the heart. Furthermore, its complex interpretations have many layers of significance which have many reflections on the contemporary social and physical structure of the city. Its influence is still present today, “as a reference point for the new forms of public space,”28 as already highlighted by Mumford. This has already been highlighted by several historians in the recent decades, but without a complete frame of interpretation of the theme.

Moreover, the need for a discipline for the appropriate design of public space seems as valid today as it was in the 1950s. “The elements of social life, the associative life, are in decay. Where can the masses gather?”29 Giedion asked in the 1950s while a similar question can also be posed in the contemporary debate about the design of public space. The heart undeniably seems to be recognised as a valid humanistic idea and urban design concept which needs to be uncovered today.

Two decades of transatlantic flows of ideas of the Heart

The CIAM 8 discourse had direct and indirect influences in different urban contexts around the world. The flow of ideas starting from the meeting at Hoddesdon, which have not yet been fully described, was particularly intense in Europe and in the US. The case studies given in this book mostly concern these two continents, though other contexts might be part of the discourse too.30

This is ev...