![]()

1 Introduction

1.1 Vitaliano Donati and his collection at the Turin Egyptian Museum

Vitaliano Donati’s time, the eighteenth century, was the Age of Enlightenment; centuries of remarkable cultural, ideological and scientific changes which spread across Europe. In Turin, Carlo Emanuele III embraced the changes with the desire to promote his Court as a centre of culture. The king started a programme of renewal, modernisation and expansion in the arts, science, economy and commerce. One of the king’s projects was a scientific–commercial expedition to the Far East. This was a pioneering venture with the purpose of opening new trade routes, improving imports, exports, collecting scientific specimens and ancient artifacts, all these with considerable anticipated rewards. Carlo Emanuele III entrusted Vitaliano Donati to lead this important expedition to Egypt and the East Indies.

At the time of the expedition, Vitaliano Donati was at the apex of his career. He was a renowned naturalist and botanist, well respected by his peers for his achievements which culminated in numerous nominations and awards. He was also an intrepid traveller who studied, analysed and recorded his observations in a scientific and methodical manner, a great eighteenth century mind and arguably a forbear of today’s twenty-first-century archaeologists (discussed in Chapter 3).

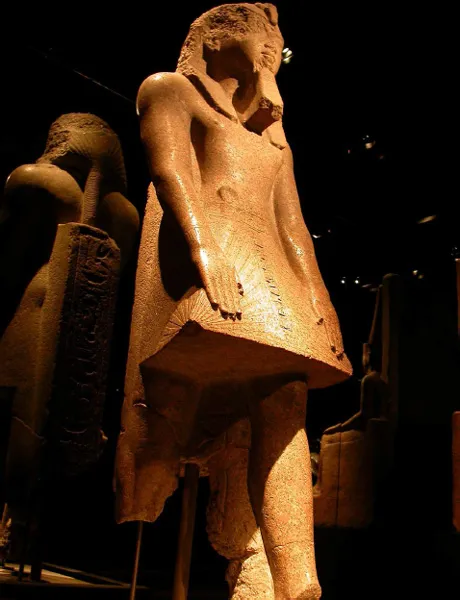

Regrettably, Donati’s collection has never been identified even though it was the first significant collection of Egyptian antiquities to arrive in Europe. The only objects that have been associated with Donati at the Turin Egyptian Museum are three large statues: an Egyptian king and two goddesses which were on display in the Statuary Hall at the time of my research (Barocelli 1912, 416; Curto 1990, 89).

In the past, lack of information impeded the identification of more of Donati’s objects, but the possibility of identifying other elements of Donati’s collection improved following my discovery in 2004 of an inventory, a packing list written by Donati (Morecroft 2005; Scattolin Morecroft 2009). This list revealed the exact quantity and type of objects that Donati collected during his journey in Egypt and it offered the possibility of cross-referencing his descriptions with unidentified artifacts at the museum, perhaps leading ultimately to their identification. The list refers to the statues but it also details many other items, and reveals how they were systematically packed in containers.

The three statues attributed to Donati by the museum are:

- 1 King Ramesses II

- 2 The goddess Sekhmet

- 3 The goddess Hathor

They are shown in Figures 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 with the descriptions provided by the museum.

The information on Ramesses II given in English on the museum plaque reads:

The king wears the nemes-headdress, a ceremonial false beard, and an apron kilt and is shown striding (unlike female figures normally shown standing with legs together). His titles appear on his kilt and on the back pillar along with the figure of his wife Queen Nefertari. Granite, Dynasty XIX, reign of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC); Temple of Mut, Thebes; Cat. 1381.

The information on the goddess Sekhmet on the museum plaque reads:

The avenging lion-goddess Sekhmet wore the sundisk attribute. Like the combative, fire-spitting goddess, the pharaoh vanquished Egypt’s enemies. Through her fire, Sekhmet was associated with the royal uraeus-cobra and the eye of the sun god Re. As the city of Thebes gained power, the priests gave Mut, consort of the God Amun, greater prominence, so she was merged with Sekhmet. Quartz-diorite: Dynasty XVIII, reign of Amenhotep III (1388–1351 BC); Thebes; Cat. 245.

The information on the goddess Hathor on the museum plaque reads:

Hathor wears the sundisk and bovine horns as her crown and carries the was-sceptre, symbol of power usually held by male deities. Her facial characteristics are modelled after those of Queen Tiye, wife of King Amenhotep III. Diorite, Dynasty XVIII, reign of Amenhotep III (1390–1352 BC), from Coptos, Cat. 694.

The attribution of Donati’s statues, in relation to his list and the other written evidence, is discussed in Chapter 7.

Since Donati’s collection was one of the founding elements of the Turin Egyptian Museum collections, the absence of information about it created a void not only in the records of Donati’s expedition to Egypt but, in a wider context, in the history of the beginning of Egyptian collections taking their places in European museums. To deny the importance of Donati’s collection is to push aside a key moment in the discovery of Egyptology, a moment in which the Western conscience awoke and became more aware of ancient Egypt and its culture.

Figure 1.1 Statue of Ramesses II at the Turin Egyptian Museum

Figure 1.2 Statue of the goddess Sekhmet at the Turin Egyptian Museum

It was important to investigate Donati’s expedition further, by re-tracing his journey, in order to gain a better understanding of the events that unfolded: their causes and effects.

1.2 Donati’s collection at the Turin Egyptian Museum: Background information

Donati’s collection was originally housed in the Royal Museum of Antiquity at the University of Turin, where it was kept from the date of its arrival, recorded as 1763 in the university register (ASUT 1763(a); ASUT 1763 (b); Morecroft 2005, 42; Scattolin Morecroft 2006; Scattolin Morecroft 2009). After its arrival at the Royal Museum of Antiquity, Donati’s collection joined a mixed group of antiquities known as the Royal Savoy collection, which was donated in 1723 by Vittorio Amedeo II of Savoia (Curto 1990, 41; Bongioanni, Grazzi 1994, 18). The recorded arrival date of Donati’s collection in 1763 is significant because it preceded Napoleon Bonaparte’s well-documented French campaign in Egypt in 1798, considered to be a milestone for the rediscovery of Egyptology.

Figure 1.3 Statue of the goddess Hathor at the Turin Egyptian Museum

In addition, Donati’s collection arrival date in 1763, confirms that it is one of the first Egyptian collections to arrive at the Turin museum, preceding the arrival of the Drovetti collection in 1824. Moreover, Donati’s collection is earlier than most others, for example the Egyptian collections in the Cairo and the Louvre museums. The British Museum was bequeathed the Sloane collection in 1753 and the Lethieullier in 1756, ten and seven years earlier, respectively, than Donati’s; however, both collections were numerically smaller than Donati’s (Scattolin Morecroft 2006, 281, footnote 5).

In 1832, eight years after the institution of the new Turin Egyptian Museum by King Carlo Felice, the collections at the Royal Museum of Antiquity were transferred to their new location in the Accademia delle Scienze building, where they joined the Drovetti collection (Orcurti 1852, 13; Curto 1990, 41). Other collections were acquired in the nineteenth century, for example in 1833 a collection of more than 1,200 objects was purchased from Giuseppe Sossio, who lived in Egypt from 1815 to 1830 and collected Egyptian objects at Thebes (Lumbroso 1879, 84; Curto 1990, 94–96). Approximately 200 objects of the Kircher collection arrived at the museum in 1894 from the Palazzo del Collegio Romano (Curto 1990, 51; Bongioanni and Grazzi 1994, 36). The Drovetti collection was purchased in 1824, and consisted of 5,268 objects, including 100 statues and 170 papyri (Vassilika 2006, listed after contents). The Schiaparelli collection contained approximately 15,000 objects, including artifacts such as the Book of the Dead of Kha and the Toilet Box of Merit, which were excavated in 1906 at Deir-el-Medina (Curto 1990, 52; Vassilika 2006, 29–30).

Further information about all these collections and later acquisitions can be found in the inventories of the Turin Egyptian Museum but, significantly, this is not the case for the Donati collection, which remained unidentified for more than 250 years after its arrival in Turin.

1.3 Donati’s collection: The written sources

The first reference to Donati’s collection can be traced to the historian Giovanni Giacomo Bonino, who mentioned Donati’s statues in his Biografia Medica Piemontese (Bonino 1825, 161). The nineteenth-century catalogues of the Turin Egyptian Museum did not include Donati’s collection, even though the information they contained can be traced back to the point of transfer of the collections from the Royal Museum of Antiquity to the new Turin Egyptian Museum in 1832. At this time a catalogue was completed by Francesco Barucchi, assistant director of the museum, recording groups of objects with no provenance or attribution. This catalogue was published in 1878 (Barucchi 1878a).

When the Orcurti catalogue was published in 1852 (Volume I) and in 1855 (Volume II), the attribution of Donati’s collection was still missing, despite the fact that the catalogue listed the objects that had been kept at the Royal Museum of Antiquity, where Donati’s collection was originally placed. In 1872 the author Fabretti referred to Donati’s collection when he mentioned the arrival of two statues at the Museum of Antiquity in Turin. However, no information about the rest of the collection was added (Fabretti 1872, 6). In the later two volumes of the Fabretti, Rossi and Lanzone catalogue (Fabretti et al., 1882, 1888), the information about Donati’s collection was reduced to only one object: a statue attributed to Donati (Fabretti et al., 1882, 107, number 1381). Information about Donati’s collection was missing in all the museum’s catalogues because they did not attribute any of the smaller objects which formed the majority of his collection.

1.4 Writings by scholars about Donati’s collection

References to some of Donati’s objects can be found in the writings of nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholars. As noted above, Bonino wrote about Donati’s statues, but he also mentioned briefly a collection of statuettes and oil lamps (Bonino 1825, 161; BCT, Bonino 1832 (a)). The authors Fabretti (1872) and Revelli (1894–96) also wrote about the statues and they described some oil lamps. It is possible that Bonino, at this earlier time (beginning of the nineteenth century), had the opportunity to look at some objects in the original crates sent by Donati before they were moved to the new building in Accademia Delle Scienze.

The twentieth-century archaeologist Barocelli, writing in 1912 about Donati’s journey in Egypt, described Donati’s statues, but he also mentioned a number of ‘idols and oil lamps’. Barocelli also estimated the number of objects that Donati collected in Egypt. The quantity (300 objects), has been used by all subsequent authors as the total number sent to Turin.

Silvio Curto, Director of the Turin Egyptian Museum (1964–84), wrote in more detail about Donati’s collection, describing more categories of objects, such as mummies, vases, amulets, ushabtis and oil lamps (Curto 1990, 88–90). However, apart from Curto’s discussion, Donati’s objects remained unknown and unattributed.

It is extraordinary that the interest in Donati’s collection was sustained after the first mention by the historian Bonino yet no additional information about Donati’s collection was uncovered over such a long period of time. The lack of information led scholars to suggest that it would be impossible to discover more (Curto 1990; Donadoni Roveri 1991). Records and inventories had been lost or destroyed over time and objects became disassociated from their provenance, increasing the problem. An example of this is the French occupation of Italy in 1799, during which objects of value were removed from the Royal Museum of Antiquity and sent to France. According to Fabretti (1872, 6–9), most were not returned to the museum, a point which is also discussed in my previous work about Donati’s collection (Morecroft 2005, 97–100; Scattolin Morecroft 2009).

In 2004 I found a reference in Revelli’s writings (1894–96, 305) mentioning the location of a document that contained information about Donati’s collection. Revelli wrote of the Collegio degli Artigianelli in Turin, but enquiries with this institution revealed that this location was no longer valid. Therefore, the possibility of finding the document came to an end. It was a new search in other institutions in Turin that led me to the Bibl...