This is a test

- 154 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Translingual Words is a detailed case study on lexical integration, or mediation, occurring between East Asian languages and English(es).

In Part I, specific examples from global linguistic corpora are used to discuss the issues involved in lexical interaction between East Asia and the English-speaking world. Part II explores the spread of East Asian words in English, while Part III discusses English words which can be found in East Asian languages.

Translingual Words presents a novel approach on hybrid words by challenging the orthodox ideas on lexical borrowing and explaining the dynamic growth of new words based on translingualism and transculturalism.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Translingual Words by Jieun Kiaer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Birth of translingual words

Like people, words around the globe are constantly on the move, and there are countless examples of foreign-born words or words with foreign heritage in our daily lives. These words are becoming so common that most of the time they do not feel foreign to us at all. As well as becoming more numerous, the identities and lives of these words are becoming increasingly complex and diverse – resembling our own migration demographics. In addition, the amount of hybrid words with different lexical origins is also increasing fast, and widespread use of social media is bringing greater amounts of subcultural words into the main lexicon. As a result, the terms traditionally used to describe the transfer from one language to another, such as ‘borrowing’ or ‘loanwords’, are inadequate in describing words with such complex and diverse stories.

In the twentieth century, the primacy of national languages meant that debates around the protection of one’s national language were prominent across the globe (Phillipson 1992, 2003). As a result, foreign-born words or words with foreign heritage were often considered outsiders in their new home languages. However, in the twenty-first century there is less of a clear distinction between native and foreign words, owing to both the sheer number of foreign words, and the increase of multilingual and multicultural societies.

As the number of languages we encounter in our everyday lives increases, so does the complexity of the origins of our words. In order to capture the nature of these words with diverse origins and complex life trajectories, I introduce the notion of translingual words in this book. Translingual words are words that live across the borders of languages. These words constantly travel and re-settle in different languages. As a part of their adaptation processes, they gain local forms and meanings. The development of social media has made this adaptation process much more diverse than before. Individuals or groups actively participate in shaping forms and meanings of these words. Unlike the pre-social media era where many people were limited to local forms of words produced by mainstream linguistic authorities or media, the advent of social media has opened the doors for ordinary people to participate actively in making, sharing, and spreading words of their own. Words on social media can have highly individualised forms and meanings, and the ease of access offered by social media has boosted large-scale communication across different languages. This large-scale communication provides crucial living environments for translingual words.

This book shows the need to shift from a monolingual lexical model into a multilingual, dynamic lexical model in order to accommodate the flexible, fluid and multi-faceted nature of the translingual words in our global lexicon.

In this book, we focus mainly on an East Asian lexical encounter with English. We aim to look at the situation in mainland China,1 Japan and Korea (mostly South)2 and additionally some data from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau. Large-scale lexical encounters between East Asian languages and English happened relatively late as we shall explore. However, it is now happening in an unprecedented scope and speed. China has been relatively slow in receiving English words compared to Japan and Korea for a number of socio-political reasons, but in recent years the English language has had a more substantial impact in China.

The lexical interaction between the non-Latinate, Sino-sphere world and the Latinate world is worth mentioning because this has caused extensive variation in the ways in which words are represented. These variations have been on the rise in recent years as ordinary people interact internationally through social media. In such cases, they tend not to follow set-ways of transcription but freely use their own means of exchange. In light of these ever-increasing variations, in this book I will use the Romanised forms of words which seem most suitable for the setting in which they are being used, rather than systematically following one or two Romanisation methods.

Unless otherwise stated, English here does not refer to a particular variety of English (i.e. US or UK English), but to varieties of English or global, international varieties of English (Crystal 2000). These varieties are not necessarily those from Kachru’s inner-circle English, but also outer and expanding circles of English. In this sense, therefore is the target of our discussion.

Tracing words’ lives: methodology

In this book I will use the following methods to trace the lives of the translingual words that I will discuss.

Using online databases

In order to justify the inclusion of a new entry or indeed, update a present entry within the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), OED lexicographers first aim to find evidence of widespread use of the word in its English form. Evidence is gathered through various means such as literary and non-literary texts, various databases, newspapers, journals, digital and print books, regional dictionaries, contributions from members of the public, specialist advice from various consultants, and even social media. In this book, using the OED’s methodology of tracing words, I am going to gather textual evidence by sieving through online databases such as Pro-Quest, Nexis, JSTOR, and Google Books to search for evidence of widespread use of words. ProQuest, JSTOR, and Google Books hold a massive collection of journals and ebooks while Nexis holds a similar database of (digital) newspapers from all over the world that can be cross-referenced when searching for keywords. Filtering through the online databases for the keywords has a twofold object – not only does it seek to find evidence of widespread use of those words in their English forms and date the first recorded instance that the word had been used in print, it also attempts to recognise how the word is being used, determining where it fits in the different parts of speech used in English (i.e. determining whether the word is used as a noun, adjective, conjunction, interjection, etc.).

Social media

Part of the methodology for this study will examine social media in order to trace the online lives of translingual words. This methodology will consist of content analysis of comments featuring the selected words made on popular social media platforms, with a particular emphasis on Twitter. Twitter is open to the general public for academic purposes and no identifiable information has been included in Tweets featured in this study. As Twitter allows users to search by hashtag and features accurate time stamping for each Tweet, we will be able to track any potential linguistic developments over the past ten years. As relatively less data is available pre-2008, we will be using data from social media from 2008 to the present.

Google Trends and Google N-gram

I will also use Google Trends and Google N-gram in order to trace the lives of translingual words in many varieties of English, not limited to the inner-circle speakers (Kachru 1985) of English. As we shall explore, many subcultural words born in East Asia have entered into World English through Southeast Asian varieties of English. Making use of Google Trends and Google N-gram can help assess these usages in varieties of English found in the outer or expanding circle of English speakers, as they become increasingly more important in the diversification of the English lexicon.

Notes

1 In this book ‘China’ will refer primarily to mainland China.

2 In this book ‘Korea’ will refer primarily to South Korea, unless otherwise indicated.

1 Foreign words

Aliens and denizens?

James Murray (1837–1915), the first editor of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), referred to foreign words as ‘uncommon words’, and as ‘aliens and denizens’ of the English language. As a lexicographer working at the peak of the explosion of new words in the early twentieth century, he struggled with the question of how best to classify words that had entered English from other languages. Were they English words or not? On what grounds? Like most of the editors of the OED after him, he held an inclusive view as the following quote shows.

The English Language is the language of Englishmen! Of which Englishmen? Of all Englishmen or of some Englishmen? … Does it include the English of Great Britain and the English of America, the English of Australia, and of South Africa, and of those most assertive Englishmen, the Englishmen of India, who live in bungalows, hunt in jungles, wear terai hats or puggaries and pyjamas, write chits instead of letters and eat kedgeree and chutni? Yes! In its most comprehensive sense, and as an object of historical study, it includes all these; they are all forms of English.

(Murray 1911:18)

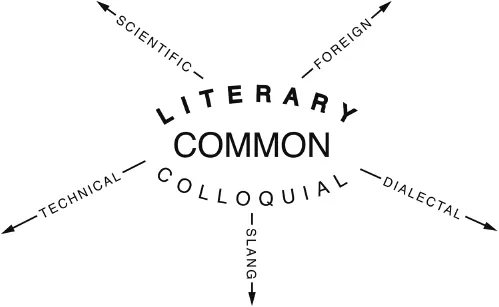

However, the decision for each word was not so straightforward. Murray himself proposed a model to classify the English lexicon (see Figure 1.1), in which he assigned literary, common, and colloquial words as the principal source of the English lexicon, and scientific, technical, dialectal, slang, and ‘foreign’ words as peripheral.

This view, however, is somewhat problematic given that the majority of common words in the modern English lexicon are of foreign coinage. English is renowned for absorbing words from other languages, and would be hard to imagine as a complete language without these words of ‘others’ (Durkin 2014). Even words we have come to associate with quintessential Englishness, such as tea, marmalade, and cottage, were originally the words of others. This is particularly true of everyday culinary words – banana, bacon, coffee, potato, tomato, chutney, noodles, chocolate, yoghurt, ketchup, broccoli, celery, carrot, kiwi, and avocado are all examples of foreign words that have become native to the English language.

Figure 1.1 Murray’s ‘circle of English’: Murray (1888: xxv).

Source: credit: OUP.

Foreign-origin words in the OED: really English?

In their 2013 book, Jones and Ogilvie depict how attitudes towards the entry of words of foreign origin into the OED changed from editor to editor, and how, contrary to popular belief, the early editors tended to favour the inclusion of foreign words in the dictionary. This was especially true of Murray, who was the chief editor from 1879–1915. Murray received suggestions from many contributors worldwide and he deemed words of foreign origin and world Englishes as ‘legitimate members of the English language’ (1888: xiv). Henry Bradley (1915–1923), Murray’s successor as chief editor of the OED, continued the inclusion of foreign words, but did not consider them ‘really English’. His opinion on Chinese words was particularly illustrative of this, with Bradley saying that ‘China has given us tea and the names of various kinds of tea; and a good many other Chinese words figure in our larger dictionaries, though they cannot be said to have become really English’ (Jones and Ogilvie 2013: 39). Murray, on the other hand, felt that the definition of ‘Englishman’ should include all speakers of English around the world, regardless of variety, claiming that ‘they are all forms of English’ (ibid.: 60). This open attitude was an exception in Victorian academia, and Murray’s dictionary was criticised as ‘barbarous’, ‘outlandish’, and ‘peculiar’ (ibid.: 54). However, this openness towards foreign-origin words did not mean that Murray saw them as equivalent to native English words, and every word in the dictionary that was considered to be foreign was marked with so-called tramlines (||).

However, the problem of how to define a word as foreign remains. Durkin (2014) shows that even pronouns like he and she have Scandinavian...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- PART I: Birth of translingual words

- PART II: East Asian words in English

- PART III: English words in East Asian languages

- Bibliography

- Index