![]()

Part I

Life

![]()

Chapter 1

Shamanic dreaming

For someone working in the field of public health, discovering the importance of tobacco in what is almost certainly its source region, Amazonia, is rather like going through Lewis Carroll’s looking glass. Suddenly what was once familiar seems strange, what was strange, familiar. Far from the source of a ‘golden holocaust’, as one book describes the western experience of tobacco without hint of hyperbole,1 in lowland South America, the region where tobacco’s relationship with humanity has been longest, the plant is widely and variously regarded as a blessing from the gods, a ‘master plant’, a spirit in its own right, a food for the spirits, and a plant with the energy to cleanse and cure. In this chapter I look at the relationship between people and tobacco in lowland South America in order to understand the place of tobacco in this particular world, and its implications for a non-human ethnography of tobacco worldwide.

Of the 50 Nicotiana species indigenous to the Americas, 41 are specifically from South America. Species diversity of this kind can occur for a number of different reasons, but the disproportionate representation of tobacco species in those parts lends support to the argument that tobacco has a long evolutionary history in the Americas.2 The tobacco species with the highest concentration of nicotine are Nicotiana tabacum and Nicotiana rustica, at 1.23 per cent and 2.47 per cent respectively. Received wisdom has it that such high levels of nicotine are the result of human domestication, but recent DNA evidence suggests that much of this evolution took place prior to any human involvement.3 For example, an ancestral parent of Nicotiana tabacum, Nicotiana sylvestris, is found in north-west Argentina and Bolivia, from where genetic evidence suggests it hybridized and moved eastwards into lowland Peru, Brazil, Paraguay and the humid Amazon forests some 200,000 years ago, long before the entry of humans into the Americas. Nicotiana rustica likewise hails from the arid landscapes of Peru, Ecuador, and the Bolivian lowlands where it evolved prior to the arrival of people.

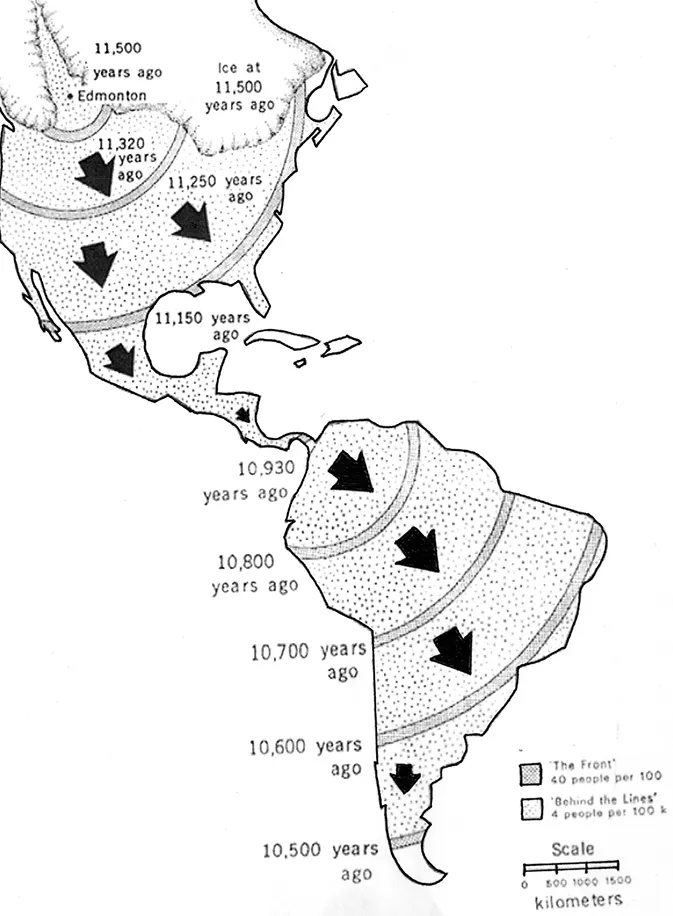

North and South America were the last continents to be settled by humans. Genetic and archaeological evidence is mixed, but one strongly argued suggestion is that this peopling took place quite rapidly from a relatively small pool of migrants, known as the Clovis people, who split off from a central Asian population in the Palaeolithic period and settled in a land bridge area called Beringia, between Russia and Alaska, where the Baring Straits now flow. They stayed in this area for anything up to 20,000 years until about 11,500 years ago, when the retreat of the Wisconsin ice sheet permitted movement down an ‘ice-free corridor’, along which bands of no more than 8,000 to 12,000 persons transited rapidly from North to South (Fig. 1.1).4

Fig 1.1 The peopling of the Americas

Source: Martin, 1973

Imagine the experience of the first people to make the transit from Beringia down the coast of what is now Alaska and British Columbia, into the warmer climes to the south. This, unlike the misguided claims made by European colonialists who came thousands of years later, really was untamed wilderness. It was not the presence of other people, their accessories and legacies that was surprising – there were none. Rather it was the diversity of plant and animal life that was a source of amazement. Instead of ‘culture shock’, as they proceeded from the permafrost terrain of Beringia into warmer, more benign and biodiverse environments, the overriding feeling the wandering bands most likely had was one of ‘nature shock’ from an abundance of beneficent nature. They preyed on mastodons and other large mammals, cumbersome creatures that were easy prey for the fleet-footed, proto-Amerindians and some of which were eventually hunted to extinction. As the first peoples came south, across the Isthmus of Panama and into the Amazon region, the range of flora and fauna became even greater.

Amongst the cornucopia of new plants and animals surrounding the early migrants arriving in South America were the impressively large and florally colourful examples of the Nicotiana species which, after millennia of waiting, “simply benefitted from…dispersion by humans beyond their original range”.5 N. rustica probably dispersed northwards into Central and North America with the help of hunter-gatherer groups before the advent of agriculture: the earliest N. rustica seeds identified in North America are from around 2,000 years ago. The archaeological record in South America is sorely lacking, but estimates here are for a much longer period – some 8,000-10,000 years – of N. tabacum domestication and use.

During this time, tobacco became strongly entwined with human life and thought. The deep history of the plant in North and, particularly, South America is reflected in the extensive range of contemporary indigenous terms for tobacco, the many myths and stories surrounding it, the diversity of ways in which it is used, and what it is used for. Chewing the leaf, drinking tobacco juice, licking its paste, using it as an enema, snuffing its powder and smoking its leaf – all can be found in different parts of North and South America, along with the paraphernalia associated with each.6 Across the Americas we find many people using tobacco smoke, spit or poultices for purification and healing purposes – amongst them its decoction and use as an embrocation for sprains and bruises, and the use of its crushed leaves as a poultice applied to wounds. However, anthropologists have tended to overlook these everyday uses in favour of more dramatic ways tobacco can be used – often in hallucinatory quantities7 – in shamanic practices, and how these practices interdigitate with indigenous perceptions and cosmologies.

Tobacco and shamanism

Shamanism is the blanket term given to a range of activities that involve certain people (shamans) moving between spiritual and physical worlds in order to effect change. To do this, practitioners must enter into an altered state of consciousness that enables them to make this transition.8 Of the at least 130 plants with hallucinogenic properties in South America that are put to use in this way,9 the one used by shamans more than any other is tobacco.10 The Matsigenka people of Eastern Peru are typical of the many groups where a shaman is “the one intoxicated by tobacco”,11 and amongst whom tobacco is “the hallmark of shamanic activity”.12 Wilbert defines the tobacco shaman as “the religious practitioner who uses tobacco, whether exclusively or not, to be ordained, to officiate, and to achieve altered states of consciousness”.13 Sometimes, tobacco is the means of creating communication with parallel, spirit worlds. Sometimes it is used as an offering to attract the spirits residing in those worlds.14 Sometimes it transports the shaman directly, its analgesic properties rendering the shaman’s body insensitive to heat and pain. However, it is its intoxicating and hallucinatory properties that make it such a central feature of shamanic healing and sorcery.

Here is an account by Gertrude Dole of the experience of a Kuikuru shaman, Metsé, imbibing tobacco in a ritual séance. It raises several themes concerning tobacco shamanism that will be returned to later in the chapter:

Metsé inhaled deeply, and as he finished one cigarette an attending shaman handed him another lighted one. Metsé inhaled all the smoke, and soon began to evince considerable physical distress. After about ten minutes his right leg began to tremble. Later his left arm began to twitch. He swallowed smoke as well as inhaling it, and soon was groaning in pain. His respiration became labored, and he groaned with every exhalation. By this time the smoke in his stomach was causing him to retch…The more he inhaled the more nervous he became…He took another cigarette and continued to inhale until he was near to collapse…Suddenly he ‘died’, flinging his arms outward and straightening his legs stiffly…He remained in this state of collapse nearly fifteen minutes…When Metsé had revived himself two attendant shamans rubbed his arms. One of the shamans drew on a cigarette and blew smoke gently on his chest and legs, especially on places that he indicated by stroking himself.15

The anthropologist Johannes Wilbert is insistent that shamanism must have come first, and envisions hunter and gatherer groups originally relying “on endogenous and ascetic techniques of mystic ecstasy rather than on drug-induced trance”.16 Siberian shamans are a good example, although Wilbert remarks how quickly the Siberians adopted tobacco into their later 16th century shamanic rituals, “thus recapturing for it the religious meaning that it has always had for the American Indians”,17 but which had been lost in its habitual and addictive use amongst Europeans. For Wilbert, the distinctive physiological and psychological effects of tobacco provide empirical, experiential support for shamanic practices, including initiations, near- and actual death experiences such as Metsé’s (above), shape-shifting and other experiences. However, his argument is that tobacco’s effects served to confirm rather than shape the “basic tenets of shamanic ideology”.18

Of course, tobacco shamanism is not ubiquitous in South America. Some groups practice forms of shamanism in ways that are ‘drug-free’.19 The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss was likewise aware that in tropical America “some tribes smoke tobacco, while adjoining tribes are unacquainted with or prohibit its use. The Nambirwara are confirmed smokers, and are hardly ever seen without a cigarette in their mouths….Yet their neighbours, the Tupi-Kawahi, have such a violent dislike for tobacco that they look disapprovingly at any visitors who dare to smoke in their presence, and even on occasions come to blows with them. Such differences are not infrequent in South America, where the use of tobacco was no doubt even more sporadic ...