![]()

1 Introduction

The Seductive Power of Immersion

Doing ‘something immersive’ is increasingly seen as a way of maintaining relevance and securing visibility in a crowded and complex content landscape. As this book will demonstrate, the quality of being immersed is facilitated in diverse ways and in a multitude of contexts. While the term has more recently been used to describe developments in the fields of Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), and mixed reality, there are many analogue experiences that can be considered immersive: street games, interactive theatre, and built environments such as theme parks and historic sites, for example. Indeed, many forms of immersive storytelling collapse the binary between physical and digital contexts, allowing holistic storyworlds to be constructed and inhabited. Immersive storytelling is exciting and evolving terrain, raising practical and ethical questions as we investigate here.

This book uses a range of current examples to explore different forms of storytelling. It understands much compelling and creative contemporary story-making to be collaborative, transmedial, multimodal, experiential, performative, and (sometimes) ungovernable. Focusing on diverse practices, the book traces different ways stories are being experienced in our contemporary mediascape, discussing what is gained and lost in different genres of immersive storytelling. It unpacks complex terms to suggest a framework within which we begin to understand the quality and promise of immersion. We critically analyse the ‘immersive turn’ within its broadest creative, cultural, technological, and social contexts, whilst recognising it as an increasingly economic and political project as well. Examples are drawn internationally, reflecting the fact that immersive media are the subject of transnational popular and scholarly attention.

We (the authors) have both been researching at the intersection of immersion and storytelling for many years, exploring diverse connections between narrative, genre, environments, and experience. Our joint perspective makes this book a unique resource; it is both critically and practically attuned, and offers ways into research design for immersive contexts. Such research raises complex methodological considerations that are often rendered invisible in the reporting of case studies; yet, this book acknowledges and confronts them head on, making our reflexivity visible, and itself a productive resource.

This introductory chapter considers some key themes, concepts, and approaches that we return to throughout the book. It uses existing scholarship to explore what we mean when we talk about ‘immersion’ and ‘storytelling’, noting that neither concept is bounded or stable. It examines why ‘the immersive’ is such a seductive concept in our present cultural, social, economic, and political moment(s), and thus why its study is important. It introduces key concepts that will underpin analyses in the book and begins to problematise meaningful distinctions between analogue/digital, physical/virtual, and online/offline.

Given the complexity of immersive storytelling as a research subject, we now offer four different approaches to sketch out where this book sits – the analogy, the experience, the history, and the definition – before concluding with an overview of the book’s structure.

The Analogy: Liquid Metaphors and the Glass-Bottomed Boat

We as researchers come to this writing project from not quite opposite, but certainly different, directions and perspectives. Alke’s background is in theatre design and she has had a fascination with how theme parks work ever since having to write a paper on English Garden Architecture as an undergraduate student. Subsequently, she investigated what museums can learn from theme park design, and became interested in how story experiences can be created without performers. Jenny’s background as a web developer and (then) digital storytelling researcher later led her to research within cultural heritage contexts, with a particular interest in their performative and digital dimensions. In recent years, that has included action research in the build, test, and evaluation stages of immersive projects. We met more than a decade ago at an event put on by a museum theatre company we were both working with at the time, albeit on different projects. This event had on the surface all the hallmarks of an immersive experience: a themed environment, a (fictional) backstory, and performers that were interacting with the audience as characters. But neither of us felt fully immersed, and at times the experience was downright uncomfortable. We have had many conversations since that time, attempting to understand what was happening.

Consulting scholarship has helped us little in our reflections on this immersive encounter: According to Matthew Reason, the term ‘immersive’ is one with ‘extremely tricky conceptual grounding’ (2015: 272). Alison McMahon proposed in 2003 that the concept of immersion in video games had become ‘an excessively vague, all-inclusive concept’ (2003: 67) and Adam Alston has more recently observed that ‘the immersive label is flexible’ to the degree that it can ‘jeapordize terminological clarity’ (2013: 128). No clear definition exists; yet, we all seem to have an idea of what we are talking about when we use that word ‘immersive’.

Maybe it is most helpful to consider, as many have done before (see Machon 2013; Lukas 2016, for example), the analogy of water to introduce the idea of immersion. This is an idea we explore in this section, as well as in the images that accompany this chapter demonstrating different practices and levels of immersion. ‘Liquid metaphors’ (Wolf 2012: 49) are tantalising because they emerge etymologically from the word ‘immersion’ itself, and they indicate that there might be different levels or degrees here to ‘get wet’: we could throw a water balloon onto, or empty a bucket of water over, somebody, ‘immersing’ them for a split second; that person could stand in a waterfall, which might mean a longer and more intensive experience; we could partly immerse somebody, like in a bathtub; or we could go into a full diving mode, sending somebody to the depths of the sea – deep immersion. In the context of crafting theme park experiences, David Younger explains how designer Tim Kirk thinks about guests as ‘Waders’, ‘Swimmers’, and ‘Divers’ – and designs experiences to allow them to choose their own level of immersion:

All of these stages of ‘liquid immersion’ have their equivalents in immersive storytelling and we will draw on some of them as examples. However, what we are really interested in is deep immersion, perhaps the most difficult to achieve and the trickiest to analyse.

Figure 1.1 ‘The Big Blue Pool’ at the Art of Animation Resort hotel at Walt Disney World is themed after the film Finding Nemo, ideal for ‘waders’ and ‘swimmers’ (in the liquid immersion sense): You can just splash about enjoying a nicely designed environment, you can connect with a story you already know, or you can become part of the story while playing (Credit: Alke Gröppel-Wegener).

The event we met at cast both of us not as being immersed ourselves, but rather as sitting in a glass-bottomed boat watching other people being immersed. Occasionally we would get splashed by water. Overall it was a bit weird. The event and our experiences of it raised searching questions about immersive storytelling as ‘form’, and about the limits of our methodologies for beginning to unpack it. This was in hindsight our initiation into the fragile and intriguing world of immersive experiences, an initiation that oriented us towards the pursuit of more – and better – opportunities for immersion. Over the years we discussed this issue, as well as going on trips to check out immersive experiences around the UK. At a catch-up meeting in late 2017, we discussed our current projects, our teaching, and how much our own processes had developed since our first meeting. We concluded that there wasn’t really a book out there that provided an accessible introduction to immersive storytelling contexts and how to approach researching them (by now ‘immersive’ was quite a buzzword and probably overused). Having wanted to do a project together for about a decade, we decided to write it ourselves.

The Experience: Story as an Agent of Immersion

Unfortunately the water analogy only gets us so far. As analogies are likely to do, it provides a model of one aspect of immersion and ignores others. Using the liquid metaphor might mean that we pay too much attention to what surrounds an individual (or individuals) having the experience, as if an experience was external, which of course it isn’t. An experience, in the way we are understanding it here, is at the end of the day an internal and subjective phenomenon. Therefore, we also need to somewhat unpick the complex notion of ‘experience’ (Lash 2006) if we want to make headway in the area of immersive storytelling.

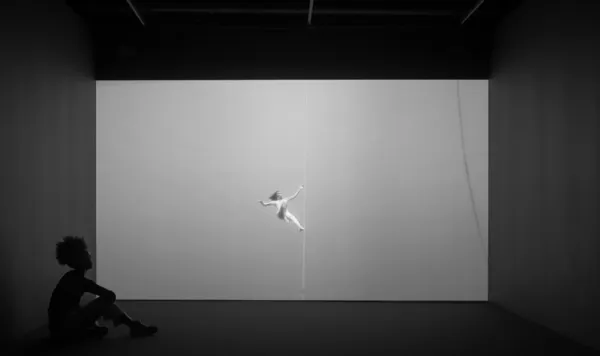

Many immersive experiences privilege multi-sensorial encounters. As Josephine Machon notes ‘in immersive practice, because all of one’s senses are heightened, it is difficult not to become acutely aware of the natural aromas of the space, of polished wood floorboards, of dank cellars, of earthy green woods’ (Machon 2013: 76). Such sensory stimulation brings participants into an immediate and felt entanglement with the practice, whether positively or negatively experienced. A number of researchers have activated multimodality as a framework through which to explore immersive work (Kenderdine 2016; Kidd 2017; Galani and Kidd 2019), an approach that makes perfect sense when thinking about examples that literally surround you, like immersive theatre, theme parks, or a 360 degree art installation such as Martina Amati’s ‘Under’ (see Figure 1.2).1

But can this also apply to our analysis of something seemingly as simple as the experience of reading a book? People often talk about ‘being immersed’ in a book, and the idea of losing yourself in a fantasy world and going on adventures with the characters you encounter there is certainly a very seductive one. Thinking about the actual medium of words on a page, it seems unlikely that books can provide immersive storytelling experiences in the manner described above, after all there is nothing to tie up the senses beyond the visual, no inclusion of taste or smell (beyond the smell of the book itself, which is probably not connected to the content of any story within), and even sight can be easily distracted in most situations you are likely to read a book.

Figure 1.2 Martina Amati ‘Under’. Installation view in Somewhere in Between at Wellcome Collection, 2018. Here, visitors find themselves in an exhibition space surrounded by large-scale video projections of freedivers in ethereal and intricate under-water performances (Credit: Wellcome Collection).

Yet, the idea of the immersive book (or story) is one that has fascinated storytellers for quite some time. The Neverending Story by Michael Ende,2 for example, tells of a boy who slowly becomes immersed in a book. The first half of the novel is about him first acquiring and then reading the book. It describes how he becomes immersed, not only in his reading (we read what he reads, but also what he thinks about what he is reading), but through his interactions with the characters. In time – and in the middle of the book the reader is reading – the boy enters the book (or story), becoming immersed in it in the most comprehensive way, by becoming a character in its narrative. The idea of entering a fictitious world is not that uncommon in both literature and film. Jasper Fforde’s Thursday Next book series, for example, portrays a protagonist who can bookjump, ‘read’ herself into books and interact with the characters in them (most of them aware that they are fictitious characters). It also happens in films, for example in The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), a film character comes into the real world from the silver screen and later takes a character from the real world into his world. In The Last Action Hero (1993), a child is given the opportunity to enter a movie and later needs to take its action hero back with him into the real world in order to track down the villain who has also escaped. In the TV series Lost in Austen (2008), a woman discovers a portal into Pride and Prejudice and ends up swapping places with the heroine and changing the narrative.

Yet, The Neverending Story (in at least some of its editions), goes a step further and cleverly ties the reader into the protagonist’s adventures by being presented as itself the book the boy is reading. When the copper-coloured cover featuring embossed snakes is described, it is difficult not to partially close the book to check the book you are holding, which is exactly as described within. When it is mentioned that there are two different colours of type within the book he holds, you realise that you have spotted the same two different colours of type within the book in your hand. Could you really be reading the same book that he is? Linking the content of the reading experience with its mode of presentation makes The Neverending Story one example where immersion is employed in a slightly different way – by making use of the real world as a touchstone that actually emphasises the experience you are having, and making the fantasy more real at the same time.3

The promise of becoming part of a story by either re-living a familiar scene or taking a protagonist’s place and changing the narrative is evidently a seductive one. Whole new genres of story-making have developed around that possibility such as CosPlay and Live Action Role Playing (LARPing).

Reading a book is about more than just reading a text then. Mangen (2008) references the multi-sensorial nature of all reading, although noting that it is a neglected area of research. ‘Haptic perception’ she notes ‘is of vital importance to reading, and should be duly acknowledged’. ‘Materiality matters’ she concludes (Mangen 2008: 405). However, analyses of these dimensions are complex given that, as Linda Candy states, ‘every human being senses the world with perceptual faculties common to us all and yet each individual differs in the exact nature of that experience’ (2014: 36). This is an important reminder that processes of participation, immersion, and interaction are not straightforward, a point we will revisit again and again in this book.

So whilst the materiality of how an immersive experience is delivered matters – be it virtual or analogue – storytelling experiences have other dimensions that we explore in this book. This is the reason why, as the title of the book suggests, story is one of the central themes we explore.

The History: Story, Interaction, and Immersion

This section traces a (necessarily brief) history of the ways storytelling, interaction, and immersion intersect. It will be seen that interaction and immersion have been central to peoples’ experiences of story through time (Ong 1982; Toolan 1988; Herman 2002). Technology has been enmeshed with these developments (although not a sole driver of them), so this section is also one that centres and is informed by media history.

The storying of events has long been understood as crucial to the development and maintenance of life and our understanding of our place or meaning within it. As Yilmaz and Ciğerci assert, ‘the history of storytelling is as old as human history’ (2018: 2). Much has been written about the ways our cultures and histories are ‘storied’, noting that storytellers themselves have tended to have a great amount of power and influence within their communities. As Howard E. Gardner notes, ‘stories, including narratives, myths, and fables, constitute a uniquely powerful currency in human relationships’ (1995: 42). Stories are ...