![]()

Part 1

The Nature of the Problem

![]()

1

The Scale and Nature of the Problem

SEAN GLYNN

It is usually assumed that interwar Britain experienced exceptionally high unemployment and that the 1930s, in particular, had much heavier unemployment than other periods. The mass unemployment of the 1930s has become a yardstick against which an ‘unemployment problem’ is often measured. In fact, the issue is not so simple and, from the perspective of Britain in the 1980s, there are very good grounds for revising the view of the period as one of uniquely high unemployment.

Unemployment was a tragedy in interwar Britain because it was prolonged and struck with devastating effects at the heart of the British industrial economy, in regions which had been relatively prosperous, where societies with a pronounced work ethic were geared to regular employment and weekly wage income for adult men. For the first time also, unemployment was officially recorded in a way not open to serious challenge; most of it could not be attributed to idleness or character deficiencies; the official figures revealed sharp increases over the pre-1920 period and truly horrendous levels in some traditional industrial areas. Unemployment was certainly an economic problem, susceptible perhaps to an economic solution, but its major role in modern British history relates primarily to its social, political and psychological effects.

As a result of the interwar experience with unemployment, faith in the market economy was finally shattered and social policies based on notions of ‘self-help’ were seen to be inadequate. These decisions were taken without any fundamental threat to the political status quo being presented and during a period when the economy progressed on all the usual indicators except unemployment. Living standards and real wages improved, on average, almost continuously and the growth record of the period was good on both historical and international comparisons. Without the unemployment problem the interwar years might now be regarded as a relatively successful period when Britain’s relative decline against other industrial nations was reversed and growth in the economy returned to late-nineteenth century levels, or better, after two decades of virtual economic stagnation.

Most of the workforce remained in employment, even in the worst years in the most blighted regions. The fortunate majority viewed unemployment in these years, as always, with a mixture of fear and compassion. At all social levels there was genuine compassion for the unemployed and their dependants and this was a real political force though it was offset to some extent by those who viewed unemployment as good social ‘medicine’ and by the lobby of middle class taxpayers who resented Exchequer support for the unemployed.

Fear was a more complex reaction: some feared unemployment itself while others feared the unemployed. Unemployment was mainly a moving stream so that, even in the best years, at least four million had direct experience and, counting dependants, as many as twelve million could be directly affected. Fear of unemployment had profound influences on social and political behaviour including industrial relations and work attitudes. Those who were protected from fears about loss of employment often feared the unemployed themselves, though it must be said that during the interwar period there are few examples of unemployed workers perpetrating mass violence. (Indeed, it could be said that they were, on occasion, the victims of police violence, notably in London.) However, the prolongation of severe unemployment was seen as a threat to political consensus and there was a real fear of political extremes which had been manifested overseas and were not entirely absent from the British scene. As Deacon shows in Chapter 3, much of the argument and agitation which did take place related to the system of unemployment relief and unemployment itself may have been seen as inevitable and beyond the control of government. By the 1940s this view had changed.

The Magnitude of Unemployment

There are major problems in defining and measuring unemployment and controversy about measurement is as old as measurement itself. All practical definitions are socially determined and must be to some extent arbitrary and subjective. All data relating to unemployment has to be used with considerable caution and this is certainly true of the interwar period [95].

The usual measures certainly suggest that the level of unemployment was exceptionally high during the period. The two most important sources of information are the 1931 census and data collected at Labour Exchanges which were established on a national basis from 1909.

National Insurance statistics commence with the registration of defined categories under Part II of the 1911 National Insurance Act which inaugurated the British National Insurance Scheme (hereafter NIS). The NIS statistics provide the basis for the official series for interwar unemployment. They are based on spot daily tallies, taken each month, of the number of people registered as ‘unemployed’ at Labour Exchanges. This is not the place for a detailed discussion of the statistics and sources, but it should be emphasized that from 1923 to 1939 the NIS covered only 60–5 per cent of the workforce, and also, that registration was not compulsory and that in particular, those not entitled to receive unemployment benefit (most married women, for example) may not have registered. It is quite clear, therefore, that the official or NIS figures seriously understate the number of people unemployed. However, because the 35–40 per cent of the workforce outside NIS was less prone to unemployment, the percentage figures based on NIS returns overstate the national percentage rate of unemployment by some 20–30 per cent. Thus if we compare NIS returns with Feinstein’s calculations based on the 1931 census we find that NIS-recorded unemployment was 2.5 million but that total unemployment was estimated to be about 3.2 million [88].

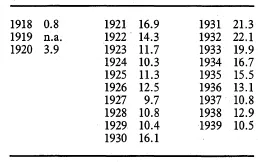

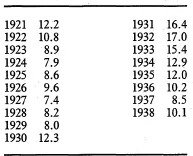

The census statistics are based upon a spot daily tally on 27 April 1931 when heads of households were asked to identify unemployment. Feinstein has compiled unemployment statistics based on revised census data with corrections based on NIS returns and making allowance for the temporarily unemployed. On this basis, using NIS statistics, it is possible to extrapolate from 1931 to get an annual series for the interwar period. Using Chapman and Knight’s estimates for man-years of employment, Feinstein estimates percentage rates of unemployment for the entire workforce, rather than the 60–65 per cent covered by NIS [54]. The official figures for unemployment of the insured (NIS) workforce are given in Table 1.1, while Feinstein’s estimates for the entire workforce are shown in Table 1.2. The former give an annual average of 14.2 per cent unemployment over the period 1921–38 while Feinstein’s

Table 1.1 United United Kingdom: Percentage of Insured Workers Unemployed 1918–39

Source: [118, table 160, p. 306].

Table 1.2 United Kingdom: Percentage of Total Workforce Unemployed 1921–38

Source: [88, table 58, p. T1281]..

estimates for the same period average 10.9 per cent. Feinstein’s revised series is not beyond criticism, but it is far the best indication of overall levels and rates of British unemployment in the interwar period. Clearly, it should be much more widely used by historians and other commentators. However, it must be strongly emphasized that the Feinstein series is not comparable with official unemployment figures before, during and since the interwar years. Census and survey data on unemployment usually reveal much higher levels than registration returns. Like the official (NIS) figures, the Feinstein series is unflattering to the interwar period when compared with official series before and since.

Data problems and deficiencies make really accurate comparisons of interwar unemployment levels with other periods virtually impossible, but such attempts are often made and the phrase ‘worst since the 1930s’ has been frequent in recent years. In the four years since 1982 the official annual average rate of unemployment in Britain has been 11.5 per cent or more and has averaged 12.4 per cent. A multiplier of 8/13 has been suggested in order to adjust interwar NIS figures to approximate comparability with those for the postwar period [194]. On this basis the interwar NIS average of 14.2 per cent becomes 8.7 which makes unemployment levels in the 1980s seem relatively severe. On the same basis of comparison, the worst annual figure of the interwar years, 22.1 per cent in 1932, converts to 13.6. The official figure for 1984/5 is 13.2 per cent. However, on the pre-1982 basis, this is estimated to be 13.7 per cent [276]. On this basis it can be said with reasonable confidence that unemployment in the 1980s has been much worse than during the interwar period and has reached levels comparable with the 1930s peak.

Comparisons with the pre-1914 period are more difficult. While trade union returns are available from the mid-nineteenth century they are based upon a relatively limited and undoubtedly biased sample of mainly skilled workers in highly unionized industries. In the interwar years unskilled workers were twice as likely to be unemployed as skilled. Before 1914 it is clear that even in boom years there was a ‘chronic surplus’ [193, 82–3] of unskilled labour in the larger urban areas [254, Part I ] and there was heavy emigration. Also, it is usually assumed that casual labour and underemployment were more common and these were manifestations of a slack labour market with endemic poverty resulting from inadequate earnings. Even the trade union returns indicate that levels of 10 per cent unemployment occurred during cyclical troughs. While pre-1914 comparisons must lack precision because of inadequacies of data, it is possible to suggest that for a large part of the workforce the incidence of unemployment in the interwar years may not have been much worse than that experienced before 1914 at least during cyclical troughs. This may be one factor in explaining public quiescence during the interwar years.

The major differences with pre-1914 lie in the disaggregated pattern, with a reversal in the relative regional impact, and in the persistence of heavy unemployment over the entire trade cycle. Before 1914 the old industrial areas on the coalfields of Britain were relatively prosperous and had a lower incidence of unemployment than London, the Midlands and the South. After 1920 this pattern was reversed and a hard core of persistent, non-cyclical unemployment emerged in the traditional industrial areas. This particular manifestation is the most distinctive feature of the interwar unemployment problem [175].

Disaggregated unemployment statistics (unemployment by duration, region, industry, occupation, age, sex) are invariably drawn from NIS returns [95]. These also have many deficiencies arising not least from variations in workforce proportions insured, administrative influences and under-registration, and should be viewed with major reservations.

It is possible to make a number of cautious generalizations. Long-term unemployment (usually defined as one year or more) was relatively low in the 1920s at 5—10 percent of total unemployment. It then rose sharply from 1929 and a hard core of about 25 per cent had developed by the early 1930s and tended to persist. This compares with about one-third of the official total in the middle 1980s. Long-term unemployment was self-reinforcing and cumulative and there is much interwar evidence to suggest that, after long periods of unemployment, men became mentally and physically unfit for work and, in effect, were outside the labour market (see Whiteside in Chapter 2).

There were considerable variations in levels of unemployment according to age and sex. Juveniles were, unlike the 1980s situation, less likely to be unemployed than other age-groups. The reasons for this are unclear and complicated. However, the answers which suggest themselves are in terms of lower wages, lower benefits, non-entitlement to benefits and under-registration. Older men in the over-40 age-groups were more prone to unemployment not because they were more likely to be dismissed but because of lower chances of being re-hired if they became unemployed.

Female unemployment is obviously subjected to massive under-recording because of ‘discouragement’. Most women were not entitled to unemployment benefits in their own right and saw little point in registration if it was unlikely to lead to employment. During the First World War there had been a sharp rise in female ‘participation’ in paid employment. The reversion to pre-1914 levels after 1920 cannot be explained simply in social or even ‘sexist’ terms. Indeed there is a good deal of evidence to suggest that female participation was economically determined. In textile areas, for example, it was traditionally higher than elsewhere. During the interwar years there was considerable regional variation in female participation and, in areas where acceptable employment was available, it increased sharply over prewar levels. In London, for example, office work became increasingly available to women and the demand for labour in general was more buoyant. That situation was reflected in increasing participation rates. This evidence together with experience since 1945 suggests that there may have been widespread female unemployment and underemployment which we cannot measure [26, 615–17].

Unemployment also had an occupational and social dimension, tending to diminish with social ranking, levels of skill and education. Unskilled workers were twice as likely to be unemployed as skilled. As Whiteside suggests in Chapter 2, unemployment acted as a filter for discrimination on social, racial and other grounds. Those groups and individuals which were subject to discrimination of one kind or another were disproportionately represented among the unemployed. This could apply to those with physical and mental differences, racial and ethnic minorities, social deviants and indeed anyone who failed to fit the acceptable stereotype. However, a series of investigations during the 1930s indicated that the Irish, who were perhaps the largest racial minority, were less likely to be unemployed than the population as a whole [100, 50–69].

Poverty, squalor and enforced idleness were certainly not new to interwar Britain. What was new was to find these conditions concentrated in the traditional industrial heartlands on the coalfields. The economic deceleration of the staple industries and the regions where they were concentrated was aggravated by linkages with other industries and through regional multiplier effects. In a relatively good year, such as 1929, NIS unemployment levels could vary regionally from 5.6 per cent in London and the South-East to 19.3 per cent in Wales. In a bad year such as 1932 differences were relatively less with unemployment at 13.5 per cent in London and 36.5 per cent in Wales. On a district basis, of course, much wider differences could be found. The pattern then is one of great regional and local variations in levels of unemployment with a fairly clear division between ‘Inner Britain’ (London, the South and the Midlands) and ‘Outer Britain’ (the rest).

The Theory of Unemployment

Understanding the unemployment problem has been complicated by the fact that economists and in particular econometricians with different theoretical approaches seem to find little difficulty in fitting their theories to interwar experience. This may reveal more about the methods of economic and econometric analysis than about the quality of economic theory or the realities of economic history. It should also be said that the quality and quantity of interwar economic data does not often justify sophisticated econometric analysis.

There are basically three theoretical economic approaches: classical, Keynesian and new microeconomie (sometimes called monetarist or neo-classical).

The classical view was probably held in one form or another by most interwar economists and was influential in the Treasury, Westminster and the City of London. Based on Say’s Law, or the notion that supply creates its own demand, and the average wage-marginal product identity, the classical view was associated in particular with Pigou [227] (but see Garside in Chapter 6). Essentially the classical view was that full employment was normal and coincided with (Walrasian) equilibrium. The economy would tend towards full employment of labour and the existence of involuntary unemployment was attributable to temporary market imperfections. Invariably, the classical view, at least in its simplest forms, attributed unemployment to ‘wage rigidity’, that is to real wages being too high (see Garside in Chapter 6). As heavy unemployment persisted throughout the interwar years and the anticipated adjustment failed to materialize, the classical view became increasingly untenable. Classical economists, including Pigou, came to recognize the social and political problems which lay in the way of real or even nominal wage reductions as a cure for unemployment and many favoured public works as a means of relieving distress arising from th...