![]()

Chapter 1

Urban transportation planning

Geetam Tiwari

CONTENTS

Introduction

Urban transport in Indian cities

Transport policy planning

Captive users

Role of the informal sector and paratransit

Alternate transport solutions

Road improvement projects

Public transport projects

What is the impact of NUTP and JNNURM?

Trends in other regions

Current knowledge base

Road to future transport

References

Introduction

Urban transport systems and city patterns have a natural interdependency. Land-use patterns, population density and socioeconomic characteristics influence the choice of transport system; at the same time the presence of certain transport systems changes land accessibility and therefore land value, triggering a change in land-use pattern and city form. Therefore city and transport plans and policies prepared by the policy makers, experts and decision makers are expected to play an important role in influencing the future health of our cities. However, a large proportion of the urban populations in Asian and other low-income cities remain outside the formal planning process. Survival compulsions force them to evolve as self-organised systems. These systems rest on the innovative skills of people struggling to survive in a hostile environment and to meet their mobility and accessibility needs. Housing, employment and transport strategies adopted by this section of society are often termed as “informal housing, informal employment and informal transport”. Squatter settlements all over the world are called informal settlements because they are not part of the official plan. The conventional definition of informal – unofficial, illegal or unplanned – denies people jobs in their home areas and denies them homes in the areas where they have gone to get jobs. Transport solutions evolved by this section of society do not become part of official policy. Their existence is mostly viewed as creating problems for “normal traffic”. Formal plans have no place for informal transport. Therefore, most cities face a complex situation where investments are for formal plans, whereas the needs of a significant section of society are met by informal transport. Is this desirable or sustainable?

In this chapter, we discuss the processes of transport policy and planning in Indian cities and compare them with examples from some other cities around the world. Policies and plans adopted by different cities in different regions of the world have a striking similarity. Official plans for Mexico city, Shanghai or Delhi may be intended for different countries, and different regions, but the disconnect between the policy documents that emphasize sustainable transport solutions, recognizing the environment and health problems of the citizens, and the projects approved for construction that primarily address the needs of car users and promote large construction projects, have strong similarities across the world.

Urban transport in Indian cities

Indian cities of all sizes face a crisis of urban transport. Despite investment in road infrastructure and plans for land use and transport development, all cities face the problems of congestion, traffic accidents and air and noise pollution. All these problems are on the increase. Large cities are facing a rapid growth in personal vehicles (two-wheelers and cars), and in medium and small cities different forms of intermediate public transport provided by the informal sector are struggling to meet the mobility demands of city residents. Several attempts have been made by planning authorities and experts to address these problems. The Rail India Technical and Economic Service (RITES) has summarised studies related to urban transport policy since 1939 (RITES, 1998). A national urban transport policy was adopted by the Ministry of Urban Development in March 2006 (MoUD, 2006). Land-use master plans prepared for most metropolitan cities have a brief chapter on urban transport. Urban transport has been given a major emphasis in the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewable Mission (JNNURM) by offering financial assistance to the state and city governments in order to prepare comprehensive traffic and transport studies and grant assistance for implementing pedestrian, non-motorised transport and public transport friendly infrastructure. The government has repeatedly made statements regarding its commitment to providing safe and sustainable transport for the masses. However, investments in road widening schemes and grade-separated junctions, which primarily benefit personal vehicle users only (car and two-wheeler users), have dominated its expenditure. The total funds allocated for the transport sector in 2002–2003 were doubled in 2006–2007. However, 80 per cent of the funds were allocated for road widening schemes. In 2006–2007, 60 per cent of the funds were earmarked for public transport, which primarily includes the metro system (Ministry of Transport and Power, Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi [GNCTD], 2006). Cars are owned by less than 10 per cent of the households in most Indian cities, except in Delhi. Therefore, an investment in car friendly infrastructure is not meant for the majority of the commuters.

In the name of promoting public transport, demands for rail-based systems – metro, light rail transit (LRT) and monorail – have been made by several cities. This is despite the fact that rail-based systems are capital intensive, and the existing metro systems in Kolkata, Chennai and Delhi are carrying less than 20 per cent of their available capacity. All three systems are running with operating losses. Without questioning the methodologies of demand projections and usage patterns, the government in Delhi has decided to expand the metro system. Similarly the state governments of Maharashtra, Karnatka and Andhra Pradesh have decided to invest in metro systems that will benefit only a small share of journeys.

Transport policy planning

At the policy level, town and country planning organisations and development authorities are expected to prepare their city master plans and city development plans. Since 1960, such plans have been prepared for several metropolitan cities. However, these plans have not been very effective in managing urban growth. Almost all cities have a slum population occupying land that is not earmarked for them.

The growth in any city is almost always accompanied with the expanding size of the urban “informal economy”. Larger cities have more slums and squatter settlements. In the million-plus and megacities in India, 40–50 per cent of the population live in informal housing (Misra, 1998). The rising cost of transport within the city combined with long working hours force the workers to live in proximity to their workplace. A large number of people living in these units are employed in the informal sector, providing various services to the outer areas of the city where new developments have been planned. The growth rate of squatter households, as compared to that of the non-squatters, is nearly four times higher in Delhi – we see a 54.2 per cent growth in squatter households compared to a 12.3 per cent in non-squatter households (Hazard Centre, 1999).

Many of the urban population living in informal settlements are captive users of low-cost travel modes (walking and cycling) because many of these residents cannot afford to pay even the low, subsidised fares for buses. For the poorest 28 per cent of the households, with monthly incomes of less than Rs. 2000, a single worker spends 25 per cent or more of their entire monthly income on daily round-trip bus fares. For those with incomes much less than Rs. 2000, the already-low bus fare is prohibitively expensive.

The impact of recent eviction and resettlement policies in Delhi has adversely affected a large number of poor households in the city. People who have been relocated have reduced access to jobs because the new residential locations are 10–15 km away from their previous residences. Hence all walking trips have to be replaced with motorised trips. Often, increased distance from the workplace has also meant increased travel time and expense.

The process of preparing master plans has been in place since 1960. Master plans are made to provide a long-term vision and guidance for the growth of the city. Yet Master Plan Delhi (MPD) 1981 and 2001 failed to provide effective guidance. In 2006, Delhi witnessed demolition of non-compliant uses on a large scale. Why is it that after nearly 50 years of master planning, cities are still struggling to meet the needs of the city residents? A large section of the city population continue to be called “illegal” residents. Is it because of poor plans, or poor implementation, or a lack of resource or expertise?

Captive users

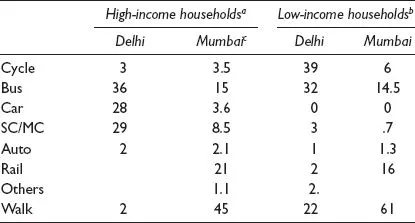

Travel patterns for people living in informal housing or slums are very different from residents in formal housing (Table 1.1). Bicycles and walking account for 66 per cent of commuter trips for those in the informal sector. The formal sector is dependent on buses, cars and two-wheelers. This implies that despite high risks and a hostile infrastructure, low-cost modes exist because users of these modes do not have any choice – they are captive users.

Table 1.1 Commuting patterns of high- and low-income households in Delhi (1999) and Mumbai (2004)

Notes: a Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) survey of high- and middle-income households (average income Rs. 7000 per month). b IIT survey of low-income households (average income Rs. 2000 per month). c Baker et al. (2004). SC/MC: Scooter cycle/Motorcycle – two-wheeled motorised vehicle, Auto: Autorickshaw – a three-wheeled motorised vehicle.

Role of the informal sector and paratransit

Urban travel in Indian cities is predominantly walking, cycling and public transport, including intermediate public transport (IPT). The variation in modal shares among these three seems to show a relationship between city size and per capita income. Small- and medium-sized cities (such as Kanpur and Ahmedabad) have a lower per capita income than the megacities. Therefore, the dependence on cycle rickshaws and cycles is greater than it is in larger cities. Delhi is showing declining trends in the three-wheeler population because of restrictions on fuel and the age of public transport vehicles.

Cities with populations of 0.1 million to 0.5 million are characterised by short trip lengths, medium density (~400–800 persons/ha) and mixed land-use patterns. Nearly 50 per cent of the trips are by walking and bicycles, and another 30 per cent are by paratransit. The two-wheeler share ranges from 15 per cent to 40 per cent in some cities and car share remains below 5 per cent (RITES, 1998). Organised public transport services under the public sector exists in few cities; however, several state-run corporations have been found to be financially unviable in the past and have been closed. In some cities, private buses have recently been introduced, but the bus transport operation is predominantly under the public sector. IPT modes such as tempo, auto and cycle rickshaws assume importance as they are necessary to meet travel demands in medium-sized cities in India such as Hubli, Varanasi, Kanpur and Vijayawada. However, there is no policy or project that can improve the operation of paratransit modes. Often, fare policy stipulated by the government is not honoured by the operators, and also the road infrastructure may not include facilities for these modes. As a result, the operators have to violate legal policies to survive in the city.

Public transport is the predominant mode of motorised travel in megacities. Buses carry 20–65 per cent of the total trips excluding walk trips. Despite a significant share of work trips catered to by public transport, the presence and interaction of different types of vehicles create a complex driving environment. Preference for using buses for journeying to work is high by people whose average income is at least 50 per cent more than the average per capita income of the city as a whole (CRRI, 1998). Although an increase in fares may or may not reduce the ridership levels, it will certainly affect the modal preference of a large number of lower-income people who spend 10–20 per cent of their monthly income on transport. A survey result shows that nearly 60 per cent of the respondents found that the minimum cost of journey-to-work trips by public transport (less than Rs. 2 per trip) unacceptable (CRRI, 1998). Even the minimum cost of public transport trips accounts for 20–30 per cent of family income for nearly 50 per cent of the city population living in unauthorised settlements. This section of the population is very sensitive to the slightest variation in the cost of public transport. In outer areas of Delhi, the presence of non-motorised vehicles and pedestrians on some of the important intercity highways with comparatively long trip lengths shows that a large number of people use these modes because they have no other option. Since a subsidised public transport system remains cost prohibitive for a large segment of the population, we should note that the market mechanisms may successfully reduce the level of subsidies; however, they would eliminate certain options for city residents.

The RITES (1998) projected modal shares show that in future bicycles and non-motorised vehicles (NMVs) will continue to carry a large number of trips in cities of all sizes. Public transport trips will be in the range of 25–35 per cent of the total number of trips. Walking trips will constitute 50–60 per cent of total trips. Despite a high share of walk trips and trips by non-motorised modes, the transport infrastructure does not include any facilities for these modes.

Alternate transport solutions

Traffic and transport improvement proposals prepared by consultants before the JNNURM included proposals for road widening, grade-separated junctions and metro systems. These projects were justified on the basis of forecasts for the next 20 years.

While the road widening and junction improvement schemes were implemented in a few cities, public transport remained in the reports only because the finances required for metro projects were beyond the capacity of state or city governments.

Road improvement projects

Several Indian cities have constructed or made plans for new flyovers. The justification for flyover construction is to reduce long delays at inter...