This is a test

- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Renaissance in Europe

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Originally published in 1933 this volume traces the history of the Renaissance in Europe and shows how its artistic manifestations differed in each successive country, drawing reference from the numerous works of art that were in the London Museums and galleries in the early 20th Century. Among other things, the book covers Sculpture, Painting, Drawing, Manuscripts, Bronzes, Ceramics, Jewellery and Glass.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Renaissance in Europe by Trenchard Cox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European Renaissance History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

The Renaissance in Europe (1400–1600)

Part I

Sculpture

(Victoria and Albert Museum; Wallace Collection; Diploma Gallery, Royal Academy; Westminster Abbey; Record Office)

Chapter I

The Italian Sculptors

ANY discussion upon Italian sculpture must inevitably begin with a mention of Florence, since it was in the Florentine firmament that the first great constellation of medieval sculptors had appeared and the early stars of the Renaissance began to rise. In Florence, from the early days of the Middle Ages, the arts had been considered an essential part of life; and the work of artists was treated there with reverence and joy. In no other city would it have been possible that a public holiday should be given in honour of a picture of the Virgin; but just such a holiday was given out of respect for the Rucellai Madonna when it was carried in a triumphal procession through the crowded streets of Florence from the master’s studio to the church of Santa Maria Novella.

At the approach of the fifteenth century, art in Florence was more than a fast preoccupation of men’s minds; it became a vital force in the public life of the city. The Guilds, each under the protection of a special saint, were not merely picturesque bodies of artistic dilettanti but an important stimulus to work and culture; they acted, indeed, as a sort of fascismo for artists, and insisted, not only upon excellence of execution, but upon efficiency of work and fulfilment of contract. A stringent system of rules was enacted by the Guilds, who treated artists and sculptors not as extraordinary beings in whom every kind of eccentricity might be condoned and each turn of temperament forgiven, but as craftsmen under contract. Artists in Renaissance Florence, were, indeed, craftsmen in the city’s service and not the lions of a vapid society, or the success of the evening at duchesses’ dinner-tables, which is all they often are today.

In no facet of the arts did Florence exact so unqualified a claim to brilliance as in that of sculpture. Sculpture indeed, was, rather than painting, the vehicle which carried the first indications of the new spirit. Even in the darkest days of the Middle Ages, the art of the goldsmith had never been lost, and at the advent of the Renaissance the metal-worker had already reached a high degree of accomplishment. Nearly every great artist of the Renaissance age was a goldsmith as well as a painter or sculptor, and his training often began with the designing of chalices or a processional cross.

The conditions of Florentine society were peculiarly conducive to the germination of the seeds of art, and now the Etruscan soil, after lying fallow for near upon two thousand years, enjoyed a renewed fertility. The interest taken by every citizen in the embellishment of the city; the unrestrained patronage of the Medici and wealthy families; and the spirit of emulation which inspired both tyrant and citizen alike, all secured for artists unlimited opportunities of attaining a high degree of accomplishment.

But as regards the sculptor, neither the favour of the tyrant nor the stimulus of Guild councils was the principal force of encouragement; to him the Church still remained the chief source of employment, with its constant demand for sculptured monuments and every form of pious artistic adornment. The great statesmen of Florence, poets and artists, public benefactors and people of note, were all immortalized by monuments from the hands of the foremost sculptors and the churches of Florence became not only places of devotion but national Pantheons and treasure-houses of revered national relics and possessions.

Between the days of Orcagna (1308 ?–68) and the beginning of the fifteenth century, there was a barren period in sculpture of about thirty years, but, early in the new century, a splendid group of young artists arose, chief of whom were della Quercia, Ghiberti, Brunelleschi and Donatello. The first three artists are not represented in the South Kensington Museum except by casts,1 but of Donatello’s production (c. 1386–1466) there is a fine display.

1 On the ground floor of the Victoria and Albert Museum are two square courts containing casts of almost every famous European work of sculpture, both medieval and Renaissance. These casts are of an immeasurable value to students of architecture and sculpture and form a collection which is unique in its completeness and range. In connexion with this chapter, the reader may find in these rooms casts of della Quercia’s famous Fonte Gaia at Siena; Brunelleschi’s bronze relief of Abraham’s sacrifice in the Bargello; and one of Ghiberti’s doors to the Florentine Baptistery, as well as many works alluded to in the course of the text. The charming Virgin and Child in the Victoria and Albert Museum was at one time ascribed to Ghiberti.

Of the original representations of Donatello’s work in the Victoria and Albert Museum, the most famous is the marble relief of the ‘Dead Christ raised by Angels’ (Pl. I (b)), in which we see that Donatello, for all his learned coquetry with antiquity, could not divest himself of the realistic trappings of the Middle Ages. In this relief, realism is the dominant note and the tragedy of death is stressed; the limp and heavy Body of Christ is being raised by angels who really mourn as they strive to lift the weight. The work is indeed terrible in its intensity, but even here a faint echo of pagan naturalism relieves the strain and the angels are not remote, celestial beings but winged children, touched with grief.

Another version of a similar subject is the small bronze relief, ‘The Lamentation over the Dead Christ’, dating from the last period of Donatello’s life (after 1450). Here the horror is even more apparent; the Virgin is gaunt with sorrow and the holy women tear their hair in an agonized frenzy of suffering. Only St. John is motionless, being bowed in a grief too deep for words. His pose of turning his back on the main figures of the composition is characteristic of Donatello’s tendency to dissipate the dramatic interest. The otherwise unbearable intensity of the central group is thus relieved. Another lovely work, of the Florentine period which followed immediately upon the visit to Rome in 1432–33, is the ‘Christ’s charge of the Keys to Peter’ (Pl. I (a)), a decoration for a sarcophagus or tabernacle. Here, the emotions are hardly less strongly marked and, although the relief is faint, the tense expression on the faces can be clearly seen and the individual mood and character of each figure can be discerned. In the figure of the Virgin, represented as an aged woman, a personal note is, perhaps, echoed; Donatello’s own mother died about the time when the work was undertaken and in this figure we may well have her portrait by her son. The landscape is only faintly indicated, but on the left, beyond the avenue of stone pines above which hovers an infant angel, is a building which closely recalls either the Castello St. Angelo by the Tiber or the Tomb of Cecilia Metellus on the Appian Way. If either of these identities were correct, it would provide an interesting reflection of Donatello’s sojourn in the Eternal City. The relief is a little masterpiece of its kind and is a perfect example of

(a) Christ’s Charge to Peter

Donatello. Victoria & Albert Museum

(b) Christ Raised by Angels

Donatello. Victoria & Albert Museum

(a) Charity

Master of the Unruly Children. Victoria & Albert Museum

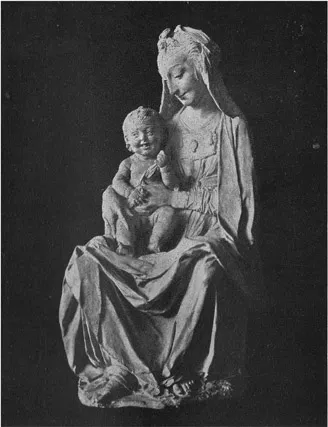

(b) Virgin and Child

Leonardo da Vinci (?). Victoria & Albert Museum

Donatello’s stiacciato work and of his treatment of aërial perspective.

Another representation of the Virgin by Donatello, in the Victoria and Albert Museum (this time conceived in a more conventional pose than in the ‘Charge to Peter’), is the large gilt terra-cotta ‘Virgin and Child’ in which the Child is represented in an unusual fashion, tightly wrapped in swaddling clothes and leaning against a chair.

The uncoloured clay model of the ‘Flagellation and Crucifixion,’ in the Victoria and Albert Museum, is a valuable illustration of the architectonic methods of the master in his later period (c. 1460). The model bears within its framework the red lily of Florence and the Lamb, the heraldic badge of the Arte della Lana1; whilst on the right of the predella is the escutcheon of the Spinelli family, and on the left the profile portrait of a young man. The work was probably a model for a monument to be erected for one of the Forzori family in some church in Florence, but the scheme was never carried out, possibly because of the death of the artist. Even the model is incomplete and shows only two out of the three intended panels—namely the left and the central groups.

1 The frame is most probably modern.

The work proclaims itself in every respect to be a product of the closing years of Donatello’s life; its affinity with the double relief of the north pulpit in S. Lorenzo is so great that authorities have more than once claimed the model to be a sketch for this pulpit relief. There are, however, certain differences in grouping and obvious discrepancies in the armorial bearings which make the theory impossible.

The model, for all its simple outlines and sketchy treatment, is an important and beautiful work. The planes are graduated in true perspective; the railing in the foreground of the left panel; the criss-cross pattern of spears and lances and the torches hoisted on high, all act as a spring-board from which to measure the receding distance and they heighten the dramatic effect. Again, the work is a mixture of fact and fancy, and even at the end of his life Donatello combined medieval realism with classical ornamentation. The scenes of the ‘Flagellation’ and ‘Crucifixion’ are tragic and intense, with the realistic motive of the ‘Scourging’ on the left, and, on the right-hand panel, the figure of the Virgin who has flung her arms apart in grief at the foot of the Cross; but these tragic figures are surrounded by motives of much lighter import, and in the spandrels are youthful winged figures, whilst on the keystones are gaily poised putti. On the predella, too, flying putti support shells with the escutcheon, while others hold garlands beneath.

A less solemn and more secular representation of Donatello’s art in the Victoria and Albert Museum is the fountain figure of the ‘Winged Cupid, bearing a fish’, which immediately invites comparison with Verrocchio’s famous work in the Palazzo Vecchio at Florence (cast in Museum). Here Donatello seems completely pagan and worships form for form’s sake. His naturalism, however, has not deserted him and the Cupid is a very typical child, enjoying the fun of carrying across his shoulders a slippery, floundering fish. This little figure is deeply expressive of the lçsson which Donatello learnt in Rome, but the classical influence is even more marked in the ‘Martelli Mirror’ (Pl. XXII (a). Whoever may be the artist of this bronze relief, the work’s claim to fame is undiminished. It is unsurpassed for its complete recapturing of the spirit of classicism, with its two main figures, Silenus and a Bacchante, confronting each other under a filigree of grapes and garlands. This little work, indeed, is the epitome of the brave new world which the artists of the early Renaissance epoch discovered in the unknown regions of antiquity.

It will, perhaps, be noticed that in almost all the works of Donatello, children play an important part. A love of children was, indeed, a characteristic trait of Renaissance artists and not the special prerogative of a single sculptor. Childish anatomy and emotions gave endless opportunities for sculptors to exercise their skill and attract their public. Certain artists, indeed, are known only by their portrayal of childhood and one, who is represented in the Victoria and Albert Museum by two celebrated works, has only the title of the ‘Master of the Unruly Children’ by which we may call him. The little group of ‘Two Children Squabbling’ is amusing enough, but the larger work, ‘Charity with three Children’ (Pl. II (a)), is a finer expression of his art and reveals deliciously the artist’s understanding of children, especially in their more informal moments when the sense of nursery decorum has deserted them, and such distractions as pinching and hair-tugging take their turn.

The work in sculpture of Andrea Verrocchio (1435–88) is represented in the Victoria and Albert Museum by the sketch-model for the tomb of Cardinal Niccolo Forteguerri and the small terra-cotta statuette of St. Jerome; but there is more interest accruing to a group in terra-cotta from Verrocchio’s workshop, ‘The Virgin with the Laughing Child’ (Pl. II (b)), which was once attributed to Antonio Rossellino and was given by Bode to Desiderio da Settignano. Recent opinion, however, has veered round to an even more interesting angle and the work is now considered as, possibly, from the hand of Verrocchio’s apprentice, the young Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). In this delicious work, the formal Madonna motive is transferred into a simple, felicitous portrayal of a Mother and Child. The Child, strangely like Verrocchio’s Boy with the Dolphin, is an engaging figure of infectious mirth, whilst the smiling Mother, markedly Leonardesque, has just that evasive enigmatic sadness which we may find again in Mona Lisa.

Another work which Bode used to give to Leonardo is the swiftly designed ‘Allegory of Discord 5 in the Victoria and Albert Museum, but more recent scholars have concluded that this mercurial relief is probably a stucco cast from a bronze—perhaps by Francesco di Giorgio (Sienese, second half of fifteenth century). Francesco di Giorgio has also been cited as the probable author of the terra-cotta statuette, the ‘Young St. John the Baptist’, in the Wallace Collection, a gracious work which was at one time thought to be by Benedetto da Maiano.

Along with Donatello and Verrocchio came a group of sculptors of whom the most notable are Agostino di Duccio; Desiderio da Settignano; Antonio Rossellino; Matteo Civitale; Mino da Fiesole; and Benedetto da Maiano.

Agostino di Duccio (1418–81) is represented at South Kensington by the impressive tomb of Sta. Giustina with its simple, flowing lines, and by the famous marble relief of the ‘Virgin and Child’ (Pl. III) which, through its insistence upon linear rhythm, and through the electric vitality in the treatment of the hair, might fittingly be described as Botticelli’s sculptural equivalent. The frozen, emotionless manner which pervades the work is relieved by a sense of realism—again concentrated on aspects of childhood. The delicious open mouths of the Virgin’s child-attendants and the natural loving way in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Preface

- CONTENTS

- LIST OF PLATES

- Introduction. The Renaissance Movement

- PART I. SCULPTURE

- PART II. PAINTING

- PART III. THE SMALLER ARTS

- Conclusion

- Index