![]()

1

Geographical and Social Structure

This chapter, covering Bahrain's geography and the important aspects of its social structure, its changing demographic trends, and its culture, sets the stage for the history and political and economic analysis that follow.

Geography

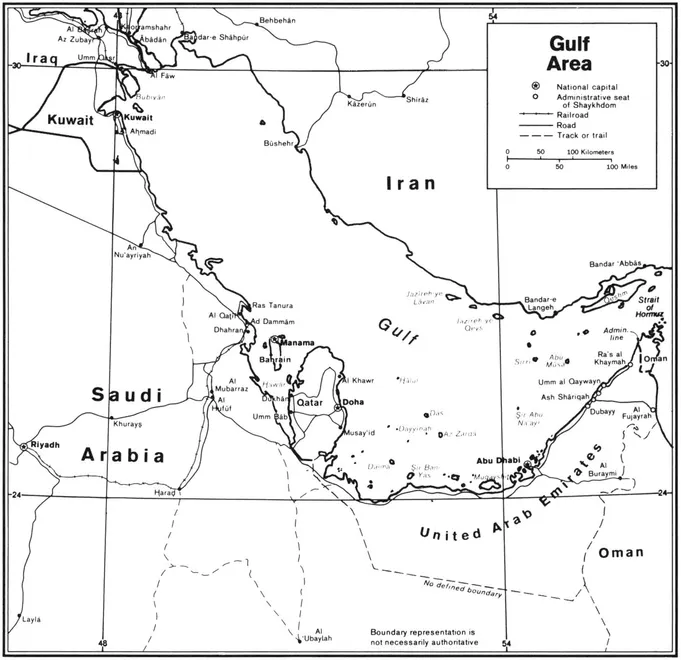

Dawlat al-Bahrain, the State of Bahrain, consists of 33 islands lying in the heart of the Gulf, approximately 24 kilometers (15 miles) off the northeast coast of Saudi Arabia and 21 kilometers (13 miles) to the northwest of the Qatar peninsula (see Map 1.1). Almost 85 percent of the country's total land area of some 650 square kilometers (250 square miles) is accounted for by the largest island in the archipelago, al-Awal (also known as Bahrain Island), which is about 16 kilometers (10 miles) wide at the northern end and tapers to a point at Ras al-Barr around 48 kilometers (30 miles) to the south. This island houses the capital city of Manama, almost all of the country's arable land, and the oil-producing area around Jabal ad-Dukhan. A causeway joins al-Awal to the adjacent island of Muharraq to the northeast—on which are located the country's second-largest city (Muharraq), the international airport, and the docks of the Arab Shipbuilding and Repair Yard (ASRY). A bridge leads from al-Awal to the island of Sitra along its eastern coast; Sitra contains the petroleum loading terminal and tank farm belonging to Bahrain Petroleum Company.

The much smaller island of an-Nabih Salih lies between al-Awal and Sitra and was in the past completely covered with date palms. Jiddah and Umm Nasan, just off the northwestern shore of the main island, are the only other notable components of the archipelago; these serve as the country's prison and as a private game preserve and garden for the ruler, respectively. The remaining islands in the group, with the exception of the more distant Hawar Islands just off the western coast of Qatar, are virtually uninhabitable.

Climatic conditions on the islands are for the most part severe; from June to September temperatures reach 48°C (120°F) and the humidity is often nearly 80 percent. During the winter months, temperatures range from 14° to 24°C (55° to 75°F), but the humidity often rises to more than 90 percent. The prevailing wind from December to March, called the Shamal, brings damp air over the archipelago from the southeast, along with occasional dust storms. Summers are buffeted by hot, dry Qaws winds from the southwest, but the hottest weeks in June may be relieved by a cooler Barra wind from the south during some years.

On those rare occasions when rain falls at all—the annual rainfall averages less than 10 centimeters (4 inches)—it tends to come in short bursts that flood the shallow dry creek beds (wadis) and hinder travel along the islands' unimproved secondary roads. Agriculture is thus dependent upon artesian springs, and the most favorable lands for cultivation make up less than 14 percent of the total land area, leaving the largest proportion of the archipelago barren.

Structure of Bahraini Society

Although Bahrain is conventionally considered a "traditional" Arab society, in which social relations are primarily determined by tribal or religious factors, such a picture of the structure of local society is seriously misleading. The country differs substantially from both Saudi Arabia, where social interaction takes a form that more closely approximates that of purely tribal or lineage societies, and Qatar, where local society is at the same time more homogeneous in ethnic and religious terms and more clearly differentiated into dominant and subordinate classes. Bahraini society shares some of the features of the societies found in the surrounding amirates, but it is distinguished by the way in which cleavages based on ethnicity, class position, and national origin overlap to produce a matrix of social relations unique to the islands.

Sectarian Divisions

Perhaps the most obvious way of characterizing Bahraini society is in terms of ethnic or sectarian composition: Somewhere around one-third of the islands' 240,000 citizens follow the tenets of the majority Sunni branch of Islam, whereas the remaining two-thirds belong to the largest of the religion's Shi'i offshoots. The precise distribution of Sunnis and Shi'a among the country's population is open to question, as the last official census in which religious identification was reported was taken in 1941. At that time, Muslims made up 98 percent of the indigenous population, of which just under 53 percent were classified as Shi'is. According to the best available estimates, the proportion of Bahraini citizens belonging to the Shi'a approached 70 percent during the mid-1980s.1 But such gross figures mask distinctions within each of these two communities that play a crucial role in structuring social and political relations in the country as a whole.

Despite their numerical disadvantage, Sunnis have formed the dominant religious community in Bahrain since at least the seventeenth century. Sunni predominance is buttressed by the fact that the country's most powerful social forces—notably the ruling A1 Khalifah family, a majority of the most prominent merchant clans, and the Arab tribes allied to the A1 Khalifah—all identify themselves with this branch of Islam. Since the last decades of the eighteenth century, when the A1 Khalifah migrated to the islands from Kuwait, religious authority has been closely tied to tribal authority; toward the end of the nineteenth century the ruler appointed a single Sunni jurist to preside over court proceedings involving personal and family disputes among the various tribes residing on the islands.

Nevertheless, Bahrain's Sunni community is split into three distinct camps: one affiliated with the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence, another following the Hanbali tradition of legal interpretation, and a third that is predominantly Shafi'i in orientation. The Maliki camp includes the A1 Khalifah and its tribal allies; adherents of this school of jurisprudence favor relatively strict interpretations of the tenets set down in the Quran and the traditions of the Prophet (Hadith), although they tolerate a degree of flexibility in applying the law under exceptional circumstances as long as the community as a whole benefits. The Hanbalis, on the other hand, are more prone to what Ignaz Goldziher calls "unquestioning belief in the literal meaning of the text" of the Quran and Hadith;2 members of the country's commercial elite who trace their origins to the Arabian side of the Gulf make up the largest part of this camp. Finally, prominent merchant families whose progenitors immigrated to Bahrain from the Persian coast during the era in which the local pearl industry was prospering follow the system of interpretation associated with the Imam ash-Shafi'i, in which the principle of consensus is a crucial criterion for establishing the validity of legal judgments. This group is known collectively as the Hawala.

Shi'is on the islands are virtually all adherents of the Twelver torm of Shi'i Islam, in which the twelfth and hidden Imam—Muhammad, the son of al-Imam Hasan al-'Askari—is revered as the once and future exemplar of religious piety. Furthermore, the Bahraini Shi'a share a long history of doctrinal and political convergence with the Shi'i populations of Iran and the pilgrimage cities of Najaf and Karbala in southern Iraq.3 Within this widespread Shi'i community, the Usuli school of legal interpretation—which accepts the Quran, the Hadith, the consensus of the community, and the exercise of intellect as equivalent bases for the authoritative derivation of doctrine and law—predominates. But significant pockets of the less rationalistic Akhbari school—which asserts the primacy of received traditions associated with the Quran and the twelve successive Imams as the foundation for both doctrine and jurisprudence— survive on the islands, as they do in isolated areas of southern Iraq.

These divisions belie the simplistic notion that Bahrain consists of a dominant Sunni majority and a subordinate Shi'i minority, the former having firm connections with the Arabian mainland and the latter strongly drawn to co-religionists in Iran and southern Iraq. In fact, serious doctrinal differences have on occasion contributed to the outbreak of severe conflicts between the Al Khalifah and the largely Hanbali tribes of eastern and central Arabia, as well as to sharp disagreements between the established religious authorities on the northern side of the Gulf and those based on the islands. Thus, religious orientation plays a significant but not a determinant part in shaping Bahraini social and political affairs. In order to understand the way that religion relates to day-to-day politics, one must consider how religious factors interact with the class and national dynamics underlying local society.

Class Structure

From a class perspective, it is useful to differentiate among three categories of forces in Bahraini society: a dominant class consisting of the central branch of the A1 Khalifah and the more prominent members of the commercial oligarchy; a class of retainers made up of the Arab tribes allied to the A1 Khalifah, the staff of the country's central administration, and the smaller traders and shopkeepers in the larger cities and towns; and a subordinate class composed of urban and rural workers, artisans and craftspeople, fisherfolk, and subsistence farmers. Conflicts of interest among these three classes have determined not only the broad pattern of coalition formation among the country's most powerful social forces but also the incidence and impact of political revolt on the islands.

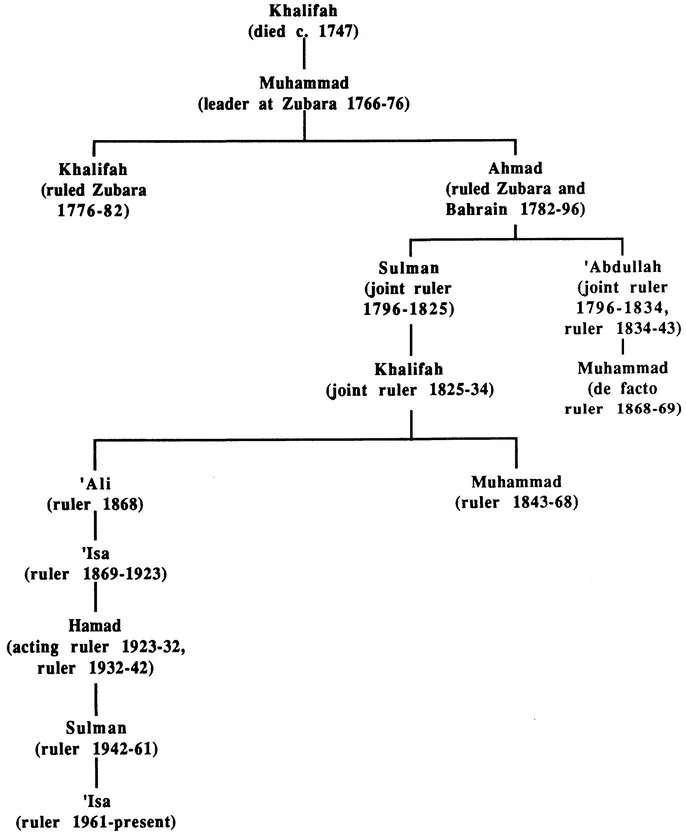

At the center of Bahrain's dominant coalition stands the A1 Khalifah, whose senior shaikhs have governed the country since the 1780s. The most powerful branch of the ruling family is composed of the direct descendants of Shaikh 'Isa bin 'Ali, who ruled the islands from 1869 to 1923 (see Figure 1.1). The shaikhs of the A1 Khalifah consolidated their control over local society by confiscating much of the agricultural land on the archipelago in the late eighteenth century and organizing it into estates managed by designated members of the ruling family for the benefit of the clan as a whole.4 It appears that the ruler himself (known as the shuyukh, or pre-eminent shaikh) administered the most important of these estates—namely, those of Muharraq Island, Sanabis, and al-Hidd—as well as the urban districts of Manama and Muharraq. Close relatives of the shuyukh held the remaining estates, subject to the ruler's approval. In more recent times, members of the A1 Khalifah have made considerable fortunes speculating on the commercial development of these lands, particularly as real estate became more profitable than date cultivation in the early decades of the twentieth century.

Bahrain's commercial oligarchy consists of a limited number of established rich merchant families with long-standing ties to the A1 Khalifah. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these

Figure 1.1

Genealogy of the Central Branches of the A1 Khalifah

Source: Angela Clarke, The Islands of Bahrain (Manama: Bahrain Historical and Archaeological Society, 1981), p. 32.

families controlled the marketing of p...