![]()

1

Introduction

Political Stability and Development

A Model of Political Stability?

Mexican politics has been notable for its stability—indeed, the Mexican regime has been uniquely stable within Latin America. Since 1973 alone, Argentina has swung from military to civilian rule twice, Chile from liberal reformist to Marxist to rightist authoritarian rule, Peru from leftist military to rightist military to civilian rule, and Uruguay from civilian to military and back to civilian rule. Similarly, we need go back only to 1964 to record two major regime transformations in Brazil; to go back a half century would be to include multiple transformations in most major Latin American nations, as well as the notoriously unstable smaller ones such as Bolivia. Not only most of Latin America but also much of the Third World beyond has found political stability an elusive goal.

Mexico has been different: Mexico has maintained the same basic political regime for well over fifty years.1 It is the only major Latin American nation not to have had a military coup in the post-World War II period. Every president selected since 1934 has survived his six-year term and then peacefully relinquished office to his successor. Since the 1940s (or even earlier), despite leadership changes, the regime has almost always held close to a basic mode of national development emphasizing political stability with economic growth. However shaken Mexico has been by the economic disasters of the 1980s, it has usually been strikingly successful in achieving these two goals. Consequently, those interested in such development, from political scientists to politicians to foreign governments to bankers, have frequently pointed to Mexico as a model, a model to be assessed and even emulated.2

What, then, does Mexico look like after its extended period of political stability? To agree that Mexico has been uniquely stable is not necessarily to agree on whether stability has been a blessing or a problem. Those who disapprove of the present situation and favor fundamental changes may well regard political stability as either a neutral fact or an obstacle to desired change. Much depends on the relationships one sees between political stability and other components of development. Some see political development in terms of a combination including regime stability, institution building, and widespread inclusion of the citizenry. Others find this definition morally bankrupt and conceive of development in terms of meaningfully independent participation or of democracy. Still others emphasize economic development, either in terms of production, industrialization, and per capita income, or very differently, in terms of resource distribution. An emphasis on resource distribution overlaps various concepts of social development, focusing on such issues as the distribution and quality of education, health care, and other services.3 Many works have attempted to explore the relationships among some of these criteria of development. Here we focus on the relationship between political stability and other development criteria. Specifically, we ask how various factors have contributed to political stability and, even more important, what political, economic, and social realities have characterized stable Mexico.

Stability amid Deep and Intensifying Problems

Political stability should not imply the absence of political (or economic and social) change and flexibility, examples of which are found throughout the book. Political stability, as used here, refers to the maintenance of the regime and its basic development model. Nor does the stability of the regime guarantee the passivity (let alone the well-being) of its citizens. There have been many protests in Mexico, including violent ones, and the regime has continually faced numerous and serious threats. That the Mexican regime is now in crisis is debatable; that Mexico itself is in crisis, in the broader sense of facing huge and recently aggravated economic and social problems, is not debatable. Mexico's crisis demands our attention, partly because of the threat it may pose to the regime's stability, but principally because the crisis itself stems from underlying problems that begin to tell us what a stable Mexico has and has not accomplished.

Chapter 2 briefly highlights the dimensions of the deep economic crisis that surfaced in the 1980s, while Chapter 5 analyzes in much greater depth the sources as well as the dimensions of Mexico's ongoing economic and social problems. Our purpose in this introduction is to give a feel for the immediacy of some of these problems in everyday Mexican life. Decades of political stability and economic growth have surely alleviated some of the terrible social and economic problems that have historically plagued Mexico. But they have just as surely not alleviated others. And this very contrast may sharpen the threat to the system's survival. For whether the result is called a revolution of rising expectations, frustrated aspirations, or relative deprivation, it is less a people's abject circumstances that tempt them to rebel than their perception that these circumstances are unnecessary and unjustified. The subjective view of what is unjustified is often made in comparison to the visible privileges enjoyed by others and to hopes dashed in times of crisis.4 We will look briefly at both long-standing problems, made keener by their juxtaposition to increasing privilege, and at new problems caused perhaps by the forward motion of development itself and aggravated by recent economic troubles.

Modernity and wealth live side by side with extreme poverty in one of the central paradoxes of Mexican development. (The sign reads "expropriated lands" and gives a file number.) (Photo courtesy of Rodolfo Romo de Vivar)

Poverty, malnutrition, disease, unemployment, underemployment, illiteracy, and inadequate education are examples of old problems that still endure, now alongside increased wealth and opportunity. Income distribution is one of the most unequal in the world, and it is becoming even more unequal (see Chapter 5). In medicine, modern facilities have expanded while many still rely on folk cures and herbs. Even according to official data, perhaps 20 percent of the population older than fourteen is illiterate, and perhaps double that figure received fewer than four years of primary education—these figures are typical of Third World nations—whereas nearly 15 percent of the population (compared to roughly 2 percent in 1960) has access to higher education, a figure close to that for much of Europe.5 Transportation offers another case of increasing contrasts. In urban settings, developed Mexico uses automobiles, taxis, or modern buses that take only as many passengers as there are seats; less developed Mexico must rely more on older buses, often packed tightly. Between cities, developed Mexico travels by plane, car, or first-class bus equipped with air-conditioning, stereo music, toilets, assigned seats, and sometimes complimentary soft drinks. The second-class buses are rarely equipped with any of these features and pack in as many passengers, often carrying fruit, fowl, and other market wares, as can be made to fit.

We have looked briefly at cases in which development has produced results for almost all to see but for only some to share. We now turn to cases in which the quality of life has actually diminished for most Mexicans, though again mostly for the less privileged. Population growth, both a product of development and a contributor to many chronic problems, illustrates the point. Mexico's population may not have been substantially larger in 1872 than it had been during the Spanish conquest three and a half centuries earlier; but, in the twentieth century, as political stability replaced revolutionary violence, the population began to soar. Additionally, development has furthered population growth by extending life expectancy. The population grew at about 1 percent per year early in this century, 1.7 percent per year in the 1930s, and 3.4 percent per year in the 1960s. Indeed, Mexico came to have one of the fastest population growth rates in the world. The population climbed to over 75 million, and roughly one in two Mexicans was under fifteen (meaning largely, although not fully, unproductive).6 As population soars, more food has to be produced, more health care and education provided, more land distributed, just to stay even. And much more employment must be created.

Perceiving the dangers of unbridled population growth, the government began to act. As "candidate" for president in 1970, Luis Echeverría boasted of his opposition to population control, eagerly presenting himself as the proud father of eight children; as president (1970-1976), Echeverría helped initiate a governmental family planning program. The birthrate has slackened impressively, from a peak of roughly 3.7 percent per year in 1977 to little over 2 percent by 1986 (with the average age finally rising), earning Mexico's National Population Council the UN's 1986 population award. President Miguel de la Madrid (1982-1988) pushed a 1 percent goal for the turn of the century.7 Nonetheless, most projections would put Mexico's population over the 100 million mark by that point.

Mexico's urbanization is another phenomenon that can be identified simultaneously with lack of development and development itself. Mexico's cities do not have industrial bases that provide sufficient employment, income, and opportunity for their citizens, yet cities grow as population grows and as frustrated but aspiring villagers leave their more traditional settings. The uprooting social effects of migration often bring special problems for the migrants themselves and for increasingly overcrowded cities.8

Mexico City, which has grown very rapidly, already has roughly 18 million people, with estimates for the year 2000 running to 26 million and more. Government efforts to reverse the trend through decentralization policies have made notoriously little headway. Not the first to push decentralization, President de la Madrid announced that no new industry would be authorized in the capital, and he advocated industrial, educational, and governmental decentralization. But centralization often builds on itself and involves not just population but economic, intellectual, and political networks. Few are willing to surrender the services and opportunities of Mexico City for the provinces. Furthermore, the economic crisis has robbed the government of the means to offer incentives and to absorb the costs of decentralization. And so life continues to worsen for Mexico City's residents. These problems have become a major theme for young Mexican writers.

Although most urban difficulties, like limited access to good water supplies, increasing drug use, and crime, affect the poor more than the privileged, many other difficulties affect all. For example, Mexico City has perhaps the worst air pollution in the world. In 1984, the U.S. State Department labeled Mexico City an unhealthy post for its employees and awarded them extra benefits for working there. A product of development— the automobile—has been a major contributor to this pollution.

Nor is pollution the only way in which the automobile makes Mexican life increasingly difficult. Mexico City's traffic jams have become unbearable; they have worsened drastically in the last decade. Residents who drive to work may spend up to four hours daily in transit. Estimates of work hours lost are staggering. The city's traffic, crowded into a few main streets, is worse than in any U.S. city, and its rush hours are far longer. Yet, despite the automobile's problems, public transportation is not a satisfactory alternative. Mexico City's metro (subway) does carry over 4 million passengers daily (more than New York City's does), and it is clean, quiet, and efficient. It expanded its routes in the 1980s. But the increased passenger load is such that for a few hours each morning and again each evening the metro is a battleground, again much worse than the subway system in any U.S. city. For their own protection in the crunch hours, women and children are literally separated from men and funneled toward different sections of the train platforms.

Amid such troubles, major oil discoveries in the 1970s offered hope. Chapter 7 will analyze how different observers have viewed the different impacts of oil on Mexican problems. For now we note that some see oil as a blessing allowing Mexico to cope with many of its chronic problems better than it otherwise could, whereas others see oil perpetuating or even aggravating these problems, as the benefits oil produces go to a few and the debt and inflation it aggravates affect all. Some evidence for both perspectives on oil's impact can be found in the economic crisis that received so much attention in the mid-1970s. It is true that oil drove economic growth from its nadir in the mid-1970s back to and even above its characteristic post-World War II rates. But it also helped to drive inflation to a new postwar high of 30 percent in 1980, a rate that had become much higher by 1982, by which time even the renewed growth halted. As we will see, oil's impact on today's economy is multifaceted.

Moreover, oil-based growth has symbolized how Mexican development has favored big industry over agriculture, especially subsistence agriculture. In fact, Mexico at present is threatened by the loss of its traditional self-sufficiency in many basic foods. Examples include corn (basic to the ubiquitous tortilla, or flat corncake), sugar, rice, beans, and other vegetables and fruits, as well as coffee and cotton. "Crude for food" is an exchange many Mexicans fear as they see themselves forced to rely on the oil-importing United States to feed themselves. Thus, in 1980, Mexico declared self-sufficiency in basic grains to be a major national goal. This declaration was an implicit admission of the failure of the "rural modernization" policies (e.g., new techniques to overcome production problems) pursued since 1940 as part of the growth-stability development model. Rural modernization never led to concomitant "rural development" (defined as progress in the way people live). In fact, rural modernization was really aimed not so much at rural but at urban development, accepting rural misery in the hope of inexpensively feeding the growing urban population.9 Despite its own suffering, rural Mexico had succeeded in feeding Mexico. Now, the regime acknowledged, new policies would be required in order to prevent even that achievement from slipping away (see Chapter 5 on the new food programs).

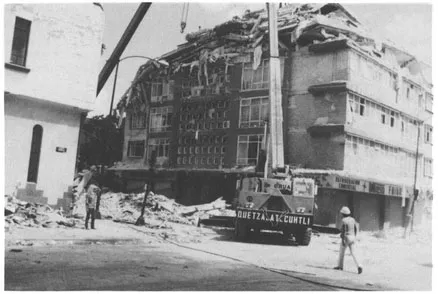

Mexico's suffering was symbolized and aggravated by the 1985 earthquakes. (Photo courtesy of Phyllis Duffy)

Cruelly, Mexico's woes were aggravated by devastating earthquakes (centered around Mexico City) in September 1985. The major quake registered roughly 8 on the Richter scale and killed perhaps 20,000 people. The quake destroyed about a thousand buildings and damaged thousands more. Many were left homeless, and Mexico was saddled with yet further human and financial burdens.10

However serious and worsening many of Mexico's social and economic problems have been, they have not, at least not yet, transformed Mexican politics. Political stability has persisted. And it has persisted despite continual assertions that a house divided against itself cannot stand, that the development/nondevelopment contradictions are too deep, that the status quo is untenable, that fundamental change is inevitable. Most works written in the 1950s and 1960s argued optimistically that political, economic, and social development criteria usually—perhaps naturally—complement and even promote one another. This had supposedly been the experience of U.S. and West European development. Because Mexico had already achieved both political stability and economic growth, many observers assumed ...