eBook - ePub

Managing In Emerging Market Economies

Cases From The Czech And Slovak Republics

Daniel S Fogel

This is a test

- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing In Emerging Market Economies

Cases From The Czech And Slovak Republics

Daniel S Fogel

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Since 1989, east-central Europe has plunged headlong into reform efforts, and firms large and small have been forced almost overnight to adapt to the demands of a market economy. This book of case studies on business development in the Czech and Slovak Republics illustrates how various industries and specific companies are responding to the challen

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Managing In Emerging Market Economies by Daniel S Fogel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Política. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Economic Situation of Central and Eastern Europe

Chapter One

Reforming the Economies of Central and Eastern Europe

DANIEL S.FOGEL SUZANNE ETCHEVERRY

This chapter surveys the issues facing five Central and East European countries (CEECs)—Bulgaria, the former Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (CSFR), Hungary, Poland, and Romania, as they proceed with transitions to market economies. Where possible, the situation of individual countries is discussed.

A general warning is necessary. The quality of data concerning the CEECs is poor. Different sources are not always consistent with each other, which affects the accuracy of the information presented. At the same time, accurate information is often limited and outdated. All data reported in this chapter should therefore be treated with caution and interpreted with these limitations in mind. Furthermore, conditions are changing rapidly and will have changed further by the time this book appears. For example, in January 1993, the Czech and Slovak Federal Republics became two separate countries. Therefore, the general analysis of the policy issues that the CEECs face in making the transition is likely to be substantially more robust than the assessment of how much progress they have made individually.

The broad story that emerges in this chapter is one of great progress made in areas where changes are relatively easy to implement. However, it is far more difficult to make institutional adjustments necessary for a market economy to function properly. Comprehensive reform programs emphasizing macroeconomic stabilization through tight fiscal and monetary policies and liberalization of prices and trade regimes have been implemented in the former CSFR, Hungary, and Poland. Similar but less-advanced programs are also formulated for Bulgaria and Romania.

Complex institutional changes are proceeding much more slowly. State enterprises must be converted to modern business organizations that are adapted to a market environment. Financial institutions must be built to support these new organizations and provide them with the capital to function in the market. Before these changes can occur, both the enterprises and the financial institutions must be separated from the core governments; each institution's role must be redefined and the revenue base secured. When this is completed, private ownership may be introduced and extended to create an incentive structure to yield better results in maintenance and the management of assets. These drastic institutional changes, required for the transition to a market economy, make the problem of the CEECs' transformations quite different from the development problem of raising per capita incomes in poor market economies.

If the CEECs are to make progress with the most difficult aspects of their transitions, they will have to resolve conflicts over constitutional arrangements, the roles of various levels of government, and the relations between them. For example, the former CSFR had problems agreeing on the role of the federal government. Disputes concerning jurisdiction, authority to raise revenues, and property ownership at the local level were, and continue to be, widespread throughout the region. There remains a serious shortage of locally based workers with the right kind of expertise to implement reform programs; people lack specific skills to build and operate market institutions. Many of the most obvious candidates for key jobs are discredited by associations with old regimes or the Communist party. Cultural and psychological change involving an adaptation to a market environment is necessary throughout the region. The gap between aspirations to Western living standards and the reality of what is likely to be achieved in the near future is a source of discontent. Most important, building and maintaining support for the reform process so that governments can see it through to completion must be a paramount consideration in its design. The factor that makes these problems particularly difficult is the large number of ethnic and nationality conflicts that weaken the cohesion of central governments and delay economic reform.

The two main features of the current economic situation in the region are the sharp declines in output and the high rates of inflation that all the CEECs have experienced. Official data probably exaggerate the output decline. Figures for 1989-1992 for countries for which there is available data indicate approximately a 10 percent decline in output for Hungary, a 12.3 percent decline in Poland, and about a 20 percent decline in Romania. In the period 1989-1991, the figures were 10 percent for the former CSFR and 20 percent for Bulgaria. There is little doubt that the decline in this period was severe.

Annual inflation during 1991 was estimated to range from nearly 40 percent in Hungary to 400 percent in Bulgaria. Poland was successful in reducing inflation sharply after its price liberalization program in early 1990, but there has been slippage, and in late 1991, the situation was in danger of deteriorating. However, the yearly inflation rate for Poland was 44.3 percent in 1992, which was slightly lower than expected. In Bulgaria, the former CSFR, Hungary, and Romania, high inflation rates reflected price liberalization programs implemented in 1991. The authorities in these countries have some confidence that they will be successful in confining the inflationary impact of liberalization to a final adjustment, but this will require that underlying fiscal positions remain under control. This will be a challenge because the reform process may erode existing revenue bases faster than new ones can be put in place. The major contributor to the sharp declines in output and to the high rate of inflation in the period 1989-1992 was the collapse of intratrade, due largely to the compression of Soviet imports to meet debt-servicing obligations and to a decline in investment. However, the most important factor may be that the old planning system has ceased to operate but the new system based on market practices has not yet been firmly put into place.

If the CEECs are to maintain stable economic conditions, each must create an institutional framework for maintaining macroeconomic control. The three items that stand out are (1) establishing a secure government revenue base, (2) creating a strong monetary control regime, and (3) ensuring that a coherent exchange-rate strategy supportive of macroeconomic stability is in place. The most difficult of these will be establishing a secure revenue base. In late 1991, all CEEC revenue bases were heavily dependent on state enterprises. Revenues in the CEECs were buoyant as liberalization programs went into effect, but this may prove to be as temporary as it was in Poland if enter-prise cash flow deteriorates. Over the longer term, as reform programs proceed and the private sector expands, the existing revenue base will erode. Introducing reasonably neutral, broadly based tax systems and ensuring that revenues are actually collected will be difficult, but rapid progress is essential.

An important systemic issue that the CEECs face is privatization. All recognize the need to shift the ownership of the majority of state assets to the private sector. Achieving this is proving difficult everywhere. Maintaining support for the process has not always been easy, and defining property rights is proving to be a serious impediment. In spite of the difficulties, however, small-scale privatization is moving forward in the former CSFR, Hungary, and Poland; Bulgaria and Romania appear to be making a good beginning. There is far less progress with large-scale privatization in all the CEECs, which is considerably more difficult because the CEECs have generally failed to develop coherent strategies for addressing the various obstacles that must be overcome, such as resistance from workers' councils in Poland and similar organizations elsewhere.

A second major systemic issue is the need to build a market-oriented financial sector to fill the important role formerly played by the central planning system. This should be done by mobilizing savings and allocating credit. Replicating the more sophisticated elements of international financial markets is not necessary, but building a basic banking system capable of providing an effective payment system is a high priority, and certain nonbanking financial intermediaries could play a positive role.

The transitions in the CEECs are taking place within the broader context of an interdependent global economy. Restrictions on access to markets in OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries are a serious handicap to the CEECs. Removing explicit trade restraints applying to agriculture, textiles, and steel and avoiding the abuse of instruments such as antidumping are arguably the most important contributions OECD countries could make toward the success of the transition. In agriculture, export capacity in the CEECs is likely to rise, adding to the existing problems of oversupply and low prices on world markets from disposal of surpluses, unless broader policy reforms in OECD countries are put in place. If rural incomes in the CEECs do not benefit from productivity improvements, migratory pressures are likely to be intensified. The interdependence between developments in world agricultural markets and economic conditions in the CEECs reinforces the need for substantial reforms of agricultural policies in OECD countries.

The Main Features of the CEEC Economies

Size and Structure

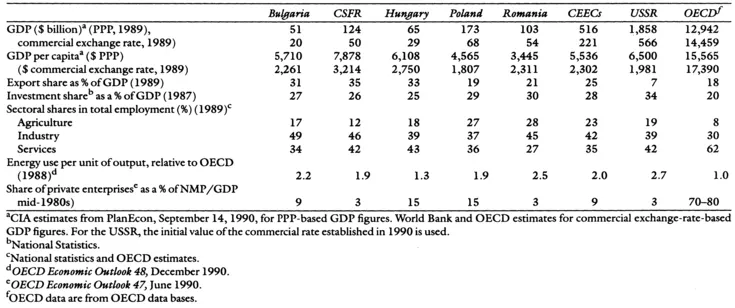

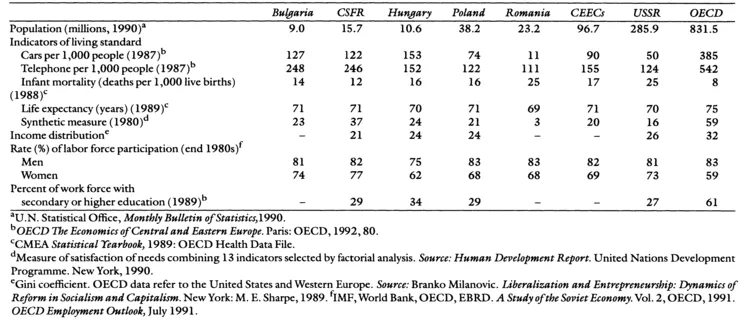

Tables 1.1 and 1.2 report some economic and social indicators that provide an overview of the size and structure of the CEEC economies. For comparison, figures for the OECD area are also provided. CEEC official figures are suspect because central planning suffered from conceptual limitations and inaccuracy. Furthermore, until recently the exchange rate used to allow cross-country comparisons was arbitrarily chosen. On a purchasing power parity (PPP) ba

TABLE 1.1 Economic Indicators

TABLE 1.2 Social Indicators

sis, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) estimates put the size of the gross domestic product (GDP) in the CEECs in 1989 at around $530 billion, similar to that of Canada, and that of the former USSR at around $1.86 trillion, nearly as large as that of Japan. The World Bank estimates for the CEECs based on commercial exchange rates are far lower. These put the CEEC GDP at around $220 billion, similar to that of the Netherlands. On the basis of GDP figures converted at the initial value of the commercial exchange rate established in 1990, GDP in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is around $570 billion.1

Given that the population in the CEECs and the former USSR is nearly half that of the OECD area, even the relatively high CIA estimates suggest low levels of development and living standards. GDP per person appears to be highest in the former CSFR; CIA estimates put it at half the average for the OECD area, and World Bank estimates it at less than 20 percent of the OECD average. The lowest GDP per capita is either in Romania with a GDP at just over 20 percent of the OECD average according to CIA estimates, or in Poland with just over 10 percent of the OECD average according to the World Bank. The indicators of living standards reported in Table 1.2 broadly confirm this picture. Diffusion of cars and telephones is low, infant mortality is high, and life expectancy is short throughout the region. A wider index prepared by the UN Development Program suggests that this is representative of other indicators not shown here. These social indicators confirm that within the region, standards in the former CSFR were relatively high and those in Romania were particularly poor.

Many structural features of the CEECs' economies reflected the emphasis placed by central planning on rapid capital accumulation and extensive development rather than on labor efficiency in industry. Although raising living standards was an objective, priority was given to defense and heavy industry at the expense of consumer goods and of services generally. Furthermore, the incentives to improve farm productivity were poor, so large proportions of the labor force needed to be retained for agriculture. As a result, the economic structures in the CEECs appeared markedly different from those of most OECD countries. In 1987, before the crisis that led to the collapse of central planning became folly evident, approximately 28 percent of the CEECs' share of GDP was devoted to fixed investments, compared to the OECD's average of 20 percent. Employment in industry averaged nearly 40 percent of the labor force, was substantially higher in Bulgaria, the former CSFR, and Romania, and compared with 30 percent in the OECD. In agriculture, employment averaged around 20 percent of the labor force, with wide fluctuations among the CEECs; the employment figure for the OECD was just 8 percent. The figure for employment in services was just over 40 percent in the former USSR and approximately 35 percent in the CEECs, which is low in comparison to die 55-70 percent range of most OECD countries. A feature of the CEECs that was not unusual by international standards was their openness, as reflected in the share of exports in GDP. However, a large share of intra-CEEC trade was carried out on a barter basis, leaving the region largely insulated from the international economy.

That the planning process failed to be guided by a coherent price structure left a legacy of problems. One is that domestic prices were forced to adjust both to domestic costs and to world prices. Many enterprises appeared not to be viable even if they achieved substantial reductions in staffing levels. Price distortions in the late 1980s were very high. This suggests that if world price levels were allowed to assert themselves, sectors in which input costs exceeded the value of output, that is, value added was negative, would represent 19 percent of the manufacturing output in the former CSFR and 24 percent in Hungary and Poland. If those figures are correct, no exchange-rate policy or strategy toward control of wage costs would have been able to solve the problems that early removal of trade barriers and subsidies would cause in these sectors. A significant part of the manufacturing sector would simply disappear unless rapid changes in production methods were made. There are limitations to the input-output approach on which this study is based, but it is instructive to note that at least one of the few industrial sectors in the region whose main inputs and outputs were subject to a transparent market test, that is, Soviet oil refining, is a concrete case where value added at world prices appears to be negative.2

A second problem is that plentiful energy supplies in the former USSR, which were made available to the CEECs on favorable terms, led to a strategy of energy-intensive develo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- PART ONE THE ECONOMIC SITUATION OF CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE

- PART TWO MANAGERIAL BEHAVIOR AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP

- PART THREE PRIVATIZATION AND MEETING MARKET DEMANDS

- PART FOUR CONCLUSION

- List of Acronyms

- About the Book and Editor