- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Modern Malay

About this book

First published in 1928, this book us a very complete survey of the Malay Peninsula, its physical aspects, its history, laws government, and present day problems; while a large part of the book is devoted to a study of the Malay himself. Mr. Wheeler, who has travelled far and wide, has spent seven years in Malay, and the thorough research which has gone to the making of the book is backed up with personal experience and observation, with the result that the book is as readable as it sounds.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

INTRODUCTORY

CHAPTER I

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

THE visitor to Malaya will at first see little of the Malays. He will arrive at Singapore or Penang, the only ports of any real consequence at present in the whole country, Singapore, of course, being much the most important; and as far as first impressions go he might be landing in any Chinese port under British influence, such as Hong-Kong or Shanghai.

Both places are in the Crown Colony of the Straits Settlements and bear the typically European outline of any British Possession. Wharfs and steamers, fine Government buildings, offices and large European shops, churches, hotels, forts, broad streets, crowds of motor-cars and all the outward signs of British imperialism meet the eye. Otherwise the picture is Chinese, particularly in Penang, where the harbour is crowded with broad, square-built Chinese boats of all descriptions, with a painted eye at the bows so that the craft may see its way through the water, On shore the impression deepens; 90 per cent, of the crowds that jostle on roads and walks are Chinese, whether in European or native costume; the only vehicles on the road in any number besides motor-cars are the ubiquitous rickshaws; except for the big stores or “go-downs,” 90 per cent, of the shops are Chinese, too, with long hanging signs covered with the customary Chinese characters which every patriotic Chinese—and which of them is not?—feels it essential to have, whether he and his customers can read the obsolescent cumbrosities or not. The narrow, crowded lanes that run into the broad thoroughfares are entirely Chinese in aspect and population.

Europeans, mostly Britishers, are in evidence in all the more open spaces, walking or riding on their lawful occasions with an unstudied air of proprietorship which they may be excused for having; but as far as mere money goes, most of them are vastly poorer than the wealthy Asiatics—Chinese again—who will be perceived to occupy a good proportion of the motor traffic, while their poorer relatives swamp the lanes and streets.

The only other people seen in any number are the various races that are grouped under the name Indians. All watchmen that sleep on truckle-beds outside stores and offices are Sikhs or Punjabis; so are many of the policemen in the streets. Fat, shaven money-lenders or “chetties” stroll leisurely along in white draperies; humble roadmakers or drivers of the primitive bullock-carts that check the progress of motor and rickshaw alike, men whose drapery, even in the middle of the fashionable quarter of a large town, consists of a scanty loin-cloth wrapped mostly above the loins, are Tamils, as are most of the clerks that are not Chinese. A few shops are kept by Muslim Bengalis in fezzes like the Egyptian tarbush; other Indian races may be recognized by the initiated, corresponding in variety and number to the numerous Celestial strains that to the ordinary observer are all simply Chinese.

About 80 per cent, of the real population, or 90 per cent, of those visible in the streets, are Chinese, and the rest mostly Indians, save for a sprinkling of Europeans and Eurasians. Malays seem hardly more numerous than the Arabs and semi-Arabs that blend in appearance with the Muslim Bengalis.

But the short but sturdy police that are not Sikhs are Malays; so are many of the motor-drivers. And the voyager to Singapore will see some boys diving for coins from primitive dug-outs or playing ball with their paddles with great dexterity as the ship comes in; these are of primitive Malay stock. Malay women are not allowed out in the streets, as Muslim women are in Egypt and Java and other places where the struggle for a living in thickly populated centres has led to a breakdown of Muslim theory, at least as far as the poor are concerned. But the few Malay men who are visible, mostly lounging in corners, look like women to the visitor, because they all wear the national skirt or “sarong” practically down to their feet, with a feminine blouse or “baju” loosely hanging over that. A sprinkling of clerks or schoolboys in ordinary European garb, and rarely a raja or religious official in dignified robes, complete the small part the people of the country play in the great ports that serve as the gateways between it and the outside world.

There are no Malay shops or offices; and hardly one mosque for ten gaudy bedragoned Chinese temples or half a dozen Christian shrines from cathedral to gospel hall.

True, these are not the Malay States. Yet there is hardly any difference in any of the towns of the Federated Malay States, nor for that matter in Johore, which is the most developed of the Unfederated ones; in the rest, the towns are hardly more than large villages.

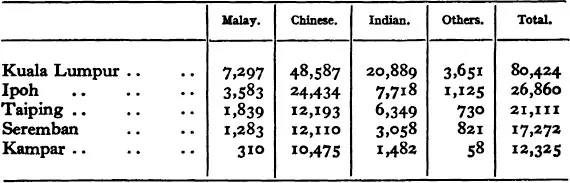

These are the figures for the populations of the five largest towns in the F.M.S. from the last Census in 1921; and the ratio has not altered perceptibly since then:—

The Malay does not flourish in cities, and has done nothing to develop them. Consequently his influence is hardly noticeable, except in one thing, and that is language. Malay is the lingua franca of the country, even in the biggest towns of the Straits; indeed, many of the huge Chinese population in Singapore cannot speak any Chinese tongue, but use a rough variation of the native language called “baba Malay” Malay is understood to some extent by members of all races, except the lowest labourers among both Indians and Chinese; and many of these are not residents, but have come in for a term of years to make what for them is a fortune before going back to their own lands, where a coolie’s wages average about 2d. a day; in Malaya they may get anything from 10d. to 2s., with a chance of fortunes if they can rise slightly in the social scale, as numbers of the Chinese do.

The Malay must be sought for in the country; and even there his presence is not conspicuous at the first glance, though the national custom of keeping the women confined to the house, which means that nearly half the population is permanently out of sight, must be allowed for.

Yet, admitting this, save for a certain number seen on the roads and railway stations, mostly engaged in doing nothing in particular, the number of Malays visible, even in the Malay States, is relatively small. The numerous railway workers, from station-masters to porters and coolies, have been till very recently practically all Indians of different types. The employees at the hotels and rest-houses where the traveller puts up are all Chinese, and this is usually the case in private European houses too.

Signs of the two great industries of Malaya will meet the traveller by road or rail almost everywhere he goes. But the tin mines are exclusively worked by Chinese, and the labourers on rubber estates are Tamils, unless they are Chinese too. Small towns, as well as large, are Chinese almost throughout.

The only big evidences of Malay industry inland are the broad ricefields which are seen in such districts as Province Wellesley and Krian, Perak; but usually they form but small patches of level green amid the heavy forest or monotonous stretches of rubber which close the view in most places from the main arteries of road and rail which run from Penang to Singapore.

On the sea coast there are often villages of picturesque huts, standing on posts over the sluggish mangrove swamps like the lake dwellings in Switzerland five thousand years ago. These represent the second main Malay craft, fishing, which is practised all round the coast and in the rivers too.

But appearances are largely deceptive. It is possible to drive through what looks like uninhabited forest, or at least plantations of coconuts and other fruit-bearing trees, for miles at a stretch; but a closer examination would very likely reveal a series of Malay villages, their little thatched houses buried under the luxuriant growth of their gardens, whose population might run into thousands where the passer-by would estimate it in tens. Of course, the nearer a river the better; for the Malay lives to-day in most respects very much like his ancestors, who came up the rivers and squatted on their banks in rough clearings and lived simply in the cool shade on the produce of easily cultivated crops and trees, varied with what fishing and hunting nearby could add.

In the Federated States, except the wild and undeveloped expanse of Pahang, the Malay population is about half that of the other races when town and country are counted together. In Pahang and the Unfederated States the proportion of Malays is much greater.

But it must not be thought that the Malays consist solely of motor-drivers and simple peasant folk. At any town or village of any size, on any of the numerous public holidays or other gatherings for State ceremonies or social events, such as welcomes to rajas or popular British officials, marriages, sports, the élite of the Malays will appear in crowds, clothed in the correct and picturesque national dress. There are chiefs and rajas of all grades, religious leaders, and numbers of Malays holding positions in the Government service, many of whom speak English perfectly, all of whom know how to behave. Then it will be seen that not only are they already profiting by English rule and education, but in addition they have a very definite and not undignified tradition of their own, far-fetched though some of their titles will appear. They have their own philosophy too: that of the countryman who is content to live and let live amid restful and natural surroundings, while strangers from the continents of Europe and Asia live feverish lives in the quest of wealth and material things. True, the Malays are by no means blind to the usefulness of such methods nowadays; but their attitude is always that of the country gentleman who regarded the advent of steam ploughs and motor tractors with a regret for the peace and contentment of the old days.

Not that the old days, in Malaya as elsewhere, have not their shadows as well as lights; shadows which for the Malays were fast turning into the darkness of total eclipse till the British Protectorate changed the gloom into the promising dawn. But there, as elsewhere, the problem is to make the best of new and old, if it be possible; in other words, to try to achieve harmony between the opposing forces of stability and change.

Few races offer a better opportunity for the study of this problem than the Malays. Their old traditions and beliefs have suffered no violent break; their docility and friendliness create a favourable atmosphere for that progress which is certainly necessary and which has already made great strides. But on the other hand a certain lassitude and passivity, partly natural, partly climatic, partly bom of Islam, are favourable to a state of stagnation which, if not vitalized by new currents, can only end in decay.

CHAPTER II

PHYSICAL FEATURES OF MALAYA

THE Malay Peninsula lies at the extreme south-east corner of Asia, being connected with Siam and Burma by the Isthmus of Kra. Malays are found in Patani and other districts within the southern borders of Siam, but the Malay States under British influence lie between 6° 30′ and 1° North latitude. This narrow isthmus allows communication with Siam and neighbouring countries; but most of the peoples who have influenced the Peninsula have arrived there from the sea.

On the east coast is the South China Sea, which is part of the Pacific Ocean. Owing to the north-east monsoon, which blows during the winter months of the northern hemisphere, despite the mouths of several large rivers, communication with this coast is difficult even in these days of steamers. To the east, about three hundred miles from Singapore, lies the great island of Borneo, full of peoples closely related to the Peninsular Malays; from the true Malays of Brunei to the Dyaks, Orang Dusun, Orang Laut and others. Further east still are the Moros in the Sulu Archipelago and the Bugis in the Celebes.

On the south is the island of Singapore, separated from the mainland of Johore by a strait about a mile wide; this is now spanned by the new causeway, which was opened for rail and road traffic in 1924. Beyond Singapore lie clusters of other islands, some quite near, like Blakang Mati, others within a few hours’ sail, such as the Karimun and Riau groups.

On the west lie the Straits of Malacca, usually calm and varying from about sixty to a hundred miles in width; beyond is the great island of Sumatra, with its daughter islands lying close. It is not surprising that the Malays have come from there and not by the overland route across steep mountains and through thick tropical forest. To the south-east lies Java, for ages the teeming home of various races, and distant from Singapore about five hundred miles through sheltered seas.

There are numerous small islands scattered round the Peninsula, but none of special importance here, except Penang on latitude 5° N., and about three miles from the mainland where is now Province Wellesley.

A MALAY HOMESTEAD; WATER BUFFALO IN THE RICE PATCH

The surface is very mountainous on the whole, as is the Isthmus of Kra. Below that in Kedah and Perlis, the two most northerly States in British Malaya, comes a belt of flat land, interspersed with limestone hills; but further south the typical mountain ranges arise which form the chief feature of the country till they die away in Johore at the southern extremity.

On the west coast, which, being sheltered by Sumatra, is not exposed to any heavy winds or seas, there are big plains and mangrove swamps formed by the alluvial soil continually washed down by the rivers, which are fed by the heavy and continuous rains. In the interior there are some wide stretches of level, lowlying land (as in the great rice district of Krian in northern Perak and Province Wellesley); but usually these are small and irregular and very marshy.

The mountains, taken as a whole, follow the line of the Peninsula in a south-east direction; many more or less distinct ranges may be distinguished. Most of them are of granitic formation of mesozoic age, with occasional traces of sedimentary rocks on their tops. The famous tin deposits of Malaya occur in or near this granite, and its extensive ranges are covered with dense tropical forest right up to the summits, as a rule. Other ranges in the east, in Pahang and Trengganu, consist of quart...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- PART I INTRODUCTORY

- PART II EARLY INFLUENCES (UP TO A.D. 1874)

- PART III RECENT INFLUENCES (FROM A.D. 1874)

- PART IV PRESENT CONDITIONS

- PART V THE PRESENT RESPONSE

- PART VI THE FUTURE OF THE PENINSULAR MALAYS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- CHRONOLOGY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Modern Malay by L. Richmond Wheeler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.