This is a test

- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Focusing on the social, economic, and political structures of the postwar global order, this collection of essays discusses the search for a new international economic order, the transformation of the nation-state and the international balance of power, the technological and strategic dimensions of the nuclear age, East-West trade and technology tr

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Global Peace And Security by Wolfram F Hanrieder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Learning Peace

What does it mean to talk about “learning peace”? It is now generally accepted in learning theory that we can only learn something that we know already. That means the existing cognitive structures have to be compatible with the new information, and an experience base has to exist for connecting the new information with what is already known. When new information is to be introduced that is incompatible with existing cognitive structures or contradicts previous experience, then groundwork has to be very carefully laid in order that the new information can be assimilated.

One problem that people in the peace education field face is that cognitive structures in the target audiences for peace education are usually organized to support win-lose thinking, a we-they attitude toward any potential adversary. These attitudes are buttressed by a social experience of competitive struggles to win in every setting from the classroom and playground to the economic and political arenas. To shift from zero-sum-game to positive-sum-game thinking and from a drive to dominate to a drive to cooperate requires more than imparting information about new approaches. It requires the construction of new mental maps about reality and a reexperiencing of that reality by the learners in ways that are intuitively convincing to them.

Much of peace education leaves cognitive structures and everyday experience untouched. Even though peace education as an acknowledged educational effort involving the preparation of curriculum materials has existed for over a century,1 nations have gone to war repeatedly during that century and today live in the dread of a nuclear war that to many seems inevitable.

It is now becoming clear that peace education has not resulted in learning peace. The longing for peace remains but is unconnected to how people think the world really works. Yet there are promising developments in peace education that involve precisely experiential learning and offer hope for the development of a less combative, more problem-oriented approach to international conflict on the part of adversary nations in our time. There are possibilities, not so much for transcending violence as for transforming, or reforming, violent behavior toward actions that will produce genuinely attractive social outcomes for the participants in conflict. This chapter will consider some of these developments.

Finding the Peace that Already Exists

One of the most important recent developments in the peace research field has been the recognition that negotiation and conflict resolution are ubiquitous processes, going on all the time in daily life. In his study of negotiation 2 Anselm Strauss has demonstrated that the ordinary business of life-whether being carried out in families, neighborhoods, the civic arena, or the world of business and industry; in schools, hospitals, and welfare agencies; or in politics-involves a process of continuous negotiation. The social order depends on this negotiation activity being carried out in the ordinary course of human affairs. Any two or more interacting human beings, in order to carry out a task that requires some degree of collaboration, must negotiate differences in definition of the situation and in perspectives on how the task can best be carried out. This is because each individual has a unique pattern of wants, needs, perceptions, and aspirations unlike that of any other individual. As a consequence, conflict of interest, in however small a degree, exists whenever human beings come together. Strauss pointed out that this conflict does not result in a war of each against all but rather results in thousands of mini-negotiations in order to arrive at mutually acceptable ways of proceeding. It applies in the management of the family toothpaste tube and in the handling of a typewriter shortage in a business office.

Because so many of these negotiations are trivial, they are not thought of as negotiations. When someone becomes intrasigent on a particular small issue, it immediately becomes obvious how important the give and take of negotiation is. Some people are better at negotiating than others are, but everyone does it, hundreds of times each day.

This is the “peace” that already exists: the peace of the negotiated social order. When the informal process of negotiation breaks down, then new behaviors are drawn on to deal with the conflict. What is important is the fact of the conflict of wants, interests, needs underlying all human interaction, and the realization that there are many ways to deal with these continually occurring differences. Because the word “conflict” has a somewhat pejorative meaning, there is a reluctance to recognize how much peacemaking we do every day. When asked to do a word association with conflict, most people would probably come up with “win.” Yet we don’t try to win: We just negotiate a mutually acceptable solution. Why? Because at a subconscious level we know that continuing good will is important for ongoing relationships. We negotiate as insurance against bad outcomes the next time a difference arises with our co-worker-which may be very soon!

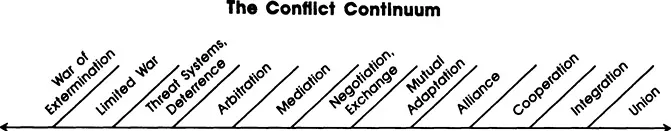

One important part of peace learning, then, is to recognize what we already do as peacemaking and to recognize the ubiquity of conflict. This paves the way for understanding that in a conflict situation there is a choice of behaviors for dealing with the conflict. Conflict management may be thought of as a continuum from total destruction of the other to complete integration with the other.

As seen in the continuum, limited war, deterrence, and threat are all on the violence side, arbitration, mediation, and negotiation are in the middle region, and various forms of cooperation and alliance are found near the integration end of the continuum. Our culture glorifies the violence end of the continuum. However, most of our behavior in both public and private life falls in the middle region, with a good sprinkling of integrative behavior to meet our deeper needs for well-being and a sense of belonging to a larger whole. When we turn to dealing with adversaries at the international level, however, the thinking of the general public and its leaders immediately shifts to the threat side of the continuum. This is the schizophrenia of nationalism.

This out-of-hand rejection of behaviors to which we have become accustomed the minute the behavioral context becomes international is what peace learning has to deal with. The Hague Peace Conferences at the turn of the century laid down the processes by which nations might gradually substitute diplomacy for war, and the League of Nations and the United Nations have each struggled with how to move nations from war and the threat of war to negotiation. The knowledge, skills, and channels of communication are all there; the confidence to apply them is lacking. “You can’t trust the_____s” is the excuse each time, although within our own society we negotiate continually with people we mistrust. Paul Pillar’s study of the processes of war termination3 shows how reluctant nations are to appear to be negotiating and what a high price that reluctance exacts from all parties.

In fact, leaders and publics alike do not feel they have a choice. Threats and deterrence are the only behaviors they feel are available to them short of submission to the enemy. Yet all nations have to make peace eventually. A reaction to the horrors of nuclear peace has brought a new type of activity into being, the activity of highly trained professionals in law, medicine, the natural and social sciences, education, and organizational development, all in the pursuit of alternative solutions to international conflict that will preclude war.4

Although Euro-North America has the greatest concentration of such groups, they are all more or less transnational and have members on all continents. These groups are introducing new dimensions to peace learning. Each from its own profession is working on a new cognitive mapping of international conflict, utilizing what its members know as scientists and professionals about how physical and social phenomena transpire. They are knowledgeable about the conflict continuum and are applying their skills to moving international political behavior from the threat to the negotiation part of the continuum. The educators continue, as they have done for so long, to develop new curriculi to educate students about alternatives. They have more to work with now than formerly, precisely because of the work of their colleagues in the sciences. They are able to present a broader and more coherent view of the interlocking nature of local-global conflict systems and of the interrelatedness of the environment, social and economic justice, and human health and well-being with the types of security policy nations choose.

The new thinking about local-global linkages (the new slogan, widely used among both professionals and peace activists, is Think globally-act locally) makes possible an experiential approach to peace learning. Relating to personal experiences was the second condition stated at the beginning of this chapter, in addition to preparing new cognitive maps of reality, for new learning to take place. Creating a new experience base is happening at two levels.

At one level there is a great proliferation of local groups concerned with the interrelated issues of peace, the environment, social justice issues, and human rights. In a country like the United States that has nearly 6,000 such local groups,5 more than half of them are strictly local in that they have no national or international affiliations; yet they are publicly identifiable. In the Third World traditional local groups primarily oriented to more place-oriented issues increasingly coexist with and are being affected by new local movements that combine traditional concerns with environmental, peace, and nonviolence issues. Examples are the Sarvodaya movement in several Asian countries, the Lokayan movement in India, the new cooperative consumer movement in Malaysia, the Council of Indigenous Peoples (representing indigenous peoples from all continents; now recognized as an NGO (nongovernmental organization) by the United Nations), and some new peace/environment/development groups forming in Africa. Latin America, with its network of peace and human rights groups stretching from Central America to Chile, has a high degree of local group activity that includes a focus on larger social issues.6

These groups are significant because they deal with global security issues in their own communities, using the tools at hand, on a physical and social terrain familiar to them. They are working on a manageable scale, getting feedback from the results of their actions. One particularly powerful aspect of some of these localist movements is the declaration of a given community or region as a zone of peace, or nuclear-free zone. Such a declaration combines a strongly internationalist political statement with a concrete local program for improving the quality of community life. At last count there were 2,840 nuclear-free cities, counties, and towns in 17 countries,7 with many Third World countries involved in getting their regions declared nuclear free.

At another level, experiential programs in dealing creatively with conflict and severe social problems are beginning to be developed for children. They are found in some of the world’s trouble spots such as in Northern Ireland,8 in communities in Israel where Arab and Israeli children go to school together,9 and in India in areas where communal violence threatens. They are found in African schools in United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) projects to gain new perspectives on Africa’s history and concrete ideas on what children can do about Africa’s future.10 They are found in Euro-North America in new organizations and publications for children, and in new types of experiential curriculum projects.11

These programs and activities all move away from abstract ideological declarations about how to approach security and peace and move toward the level of daily perception and experience, in a framework that enables people to see the connections between what they know and how the world could work more peacefully.

Cultural Mirrors and Peace Learning

A society learns about itself from looking in the mirrors its culture holds up to it. In contemporary societies these mirrors are to a considerable extent the mass media. Because the mass media in the West are the most highly developed, the mirror held up for societies in all parts of the world is a peculiar distorting mirror made in the West. As detailed in the MacBride Commission report on the world information order,12 much of what is shown in the mirror is Western stereotyping of other cultures, and much of it involves depiction of violence. The Consumer’s Association of Penang, Malaysia, found in a recent study that Malaysian children “were exposed to four killings, saw 24 guns, heard 14 gunshots and ‘witnessed’38 physical blows on an average day,”13 mostly from U.S. television programs and films such as “Dallas,” Superman, and “Kojak.” In addition to the fictional violence is of course the very real violence of local warfare and guerrilla activity taking place in many parts of the world. The violence that exists is considerably magnified by a journalistic bias toward reporting stories of violence more fully and frequently than stories of peaceful conflict-resolving activity.

The U.S. media are more violence saturated than are those of other Western countries, and they are also distributed the most widely around the world. The contrast between the cultural glorification of violence in certain forms of art, music, television, and literature as well as in newspaper reporting-all for passive spectator audiences-and the socially sensitive grassroots activism described earlier is very great. If we weigh this grassroots activism with the initially discussed reality that the great bulk of human transactions on any given day are peaceful negotiations of potentially conflictual situations, we can see that the cultural mirror reflects back a very unreal and distorted version of the actual social order. The cultural images are very persuasive, so people are easily convinced that societies are hopelessly violent by nature.

Another important task of peace learning, then, is to learn to look with a critical eye at these distorted cultural images. Looking beyond the images to the reality of human behavior does not mean creating illusions in another direction, of false peaceableness, but becoming more familiar with the actual range of human responses and learning to evaluate and choose according to how socially productive different behaviors are. More first-hand experience with reality is the best antidote to false cultural images.

Although experiential education and grassroots activism move in the right direction, one educational innovation moves in the opposite direction: the rapid increase in the use of the computer for classroom teaching. Computers per se are not to be condemned, they are an important new tool (but only a tool) for dealing with complex interactions, large-scale information systems, and open information flows on a planetary basis. Used correctly, they will enhance all other human capacities. But this right use will only happen if children are given computer training along with the memory training developed in oral tradition societies and the literacy training developed with the invention of printing. Each skill or discipline-memory, reading, and computer literacy-is an indispensable skill, along with the disciplines of fantasy, meditation, reflection, and craft skills, for the full development of the human potential. Each enhances perception of the world and enriches the capacity to act creatively.

What is to be feared is that children will become deskilled, knowing only about abstract symbolic representations of the world through computer symbols and no longer hav...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- 1. Learning Peace

- 2. Transition to Peace and Justice: The Challenge of Transcendence Without Utopia

- 3. Japan and the Future Trajectory of the World-System: Lessons from History?

- 4. On the Rise of the Fourth World

- 5. The Transatlantic Community and West European Integration: The Dynamics of Change

- 6. The Soviet Union and World Order

- 7. Promoting Technology Trade: Strategies for Suppliers and Recipients

- 8. Nuclear Fission: Reaction to the Discovery in 1939

- 9. The SDI or Star Wars? An Owlish Perspective

- 10. Ballistic Missile Defense and NATO

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- About the Editor and Contributors