![]()

1 Form

Form in the theatre

Form is the bedrock principle underlying every artwork, in whatever medium. It is its form that distinguishes an artwork from any other object that might be encountered in nature. Recent critical theory has perplexed many young artists by challenging the importance of form as an aesthetic necessity, but nothing more decisively differentiates artists from critics than the attitudes they can afford to indulge on the subject of form (especially so-called literary form, which differs fundamentally from dramatic form). In recent decades, several “lit-crit” schools of thought have quarreled with the term formalism, and thereby confused many young theatre artists about their proper professional preoccupation with form – a confusion that has led to some curious variations in style, but to no essential changes in dramatic form. What an academic critic means by moving somehow “beyond formalism,” is very distantly related to what an artist must focus on while creating works of art. For an academic critic, moving beyond the straightjacket of any one theory about form might make some sense, but form itself is all that artists deal in. It is what defines their vocation, and it is a cruel illusion to imagine that art work can continue somehow beyond acquired expertise in form. In the theatre, form is as essential (and inevitable) as it is in painting, sculpture, architecture, music, poetry, or dance, but it eludes easy detection, and most people need to be trained to perceive dramatic form. The reason for this is that dramatic form is intangible and invisible; it can be grasped and remembered only with the mind.

The elusiveness of dramatic form is one of the baffling paradoxes of the theatre. The theatre is notorious for its vibrant, larger than life presence. How could all this manifest, “in-your-face” physicality and sensuous excess result in forms that are elusive? The theatre’s glory (and frequently its shame) derives primarily from its exuberant spectacle; but it is precisely the spectacle – and all the immediacy of effect that spectacle suggests – that consistently misdirects our perception of dramatic form. The theatre is a hybrid art – some would say it is the only complete art – because it is simultaneously a visual art (within which all the creative means of painting, sculpture, and architecture are available) and a complex performance art (within which music, dance, and poetry can all find full expression). All the many spectacular dimensions of the theatre are meant to engraft themselves sensuously on our consciousness like experience itself. Dramatic form, however, is sculpted uniquely in time, and nothing is more elusive for the mind than “shapes” made in time by human artistry. We cannot even talk about them without recourse to analogies and metaphors (such as “shapes”) drawn from other arts.

A first principle for artists, according to Lessing in his Laocoön, is that “signs that follow one another [in time] can express only objects whose wholes or parts are consecutive”; and furthermore, “objects or parts of objects which follow one another are called actions” (Lessing, 1984, p. 78). Thus poetry – an art of “articulated sounds in time” – necessarily deals with actions. On the stage, although there are bodies visually present,

they also persist in time, and in each moment of their duration they may assume a different appearance or stand in a different combination. Each of these momentary appearances and combinations is the result of a preceding one and can be the cause of a subsequent one, which means that it can be the center of an action.

(Ibid.)

Such purely formal observations are of enormous practical importance to composers in the time-arts, but they are clear only if one remains undistracted by “theme” or “content.”

Form and content confusions

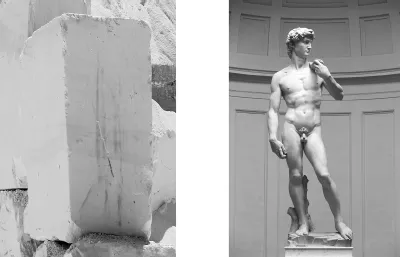

What is commonly meant by the “content” of a play is “whatever the play is about.” Story is the term that dominates popular conceptions of the theatre and obscures a clear perception of dramatic form. Story is related to our second principle, action (the subject of Chapter 2), but it obscures a practical grasp of the first principle, form. A shift to analogies drawn from sculpture can help us wean the mind off “story” when thinking formally about a play. For a sculptor – let’s say Michelangelo about to embark on creating the David – the “raw material” of his craft was a huge 18-foot block of quarried marble that had been lying in the “yard” of the Cathedral

Figure 1.1 Rough-hewn megalith of quarried marble and Michelangelo’s David.

Source: Xpixel, Stock Photo; Jörg Bittner Unna, Creative Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0.

at Florence for over a generation (see Figure 1.1). This huge block of stone (nicknamed “the Giant”) had been quarried and dragged down from the Carrara mountains with no clear idea how it would be used. From this matter, the young Michelangelo was to fashion one of the finest and best-known statues in Europe, the colossal David. What is the difference between these two pieces of stone, before and after the work of the sculptor? The rough-hewn monolith quite literally “contains” the finished David, and the finished David is missing only those portions of the original stone that were not the David – chips and shards of no value that it would have occurred to no one to save or preserve. The craft of the sculptor consisted quite simply (or rien que ça, as the French say) in chipping away from the big block all the extraneous stone that was not the statue of David.

Michelangelo left at his death a series of unfinished statues, most of them intended for the tomb of Pope Julius II (see Figure 1.2 “Captive Slaves”). These show figures emerging from half-sculpted stone and illustrate strikingly the gradual disclosure of recognizable forms from rough-hewn rock masses. Michelangelo himself stated in a poem (Michelangelo, 1991, p. 302):

Non ha l’ottimo artista alcun concetto

C’un marmo solo in sè non circoscriva

Col suo soverchio

(Not even the best of artists holds any concept

That a piece of raw marble does not already

Contain within itself)

(Author’s translation)

It is an arresting insight into the nature of form and its relation to content. Is the finished David the “content” of the sculpture? The human form that results from the carving is surely the formal distinction between the two single blocks of marble (the unfinished and the finished sculpture). If the David were a play, however, we’d already be mired in “thematic” discussions of a different sort of “content,” subjects like the Biblical David and his struggle with Goliath, or heroic nudity in pre-Christian Greece, or

Figure 1.2 Two of Michelangelo’s “Captive Slaves.”

Source: Jörg Bittner Unna, Creative Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0.

breaking sixteenth-century taboo in treating Biblical subjects, or the auxiliary “subjects” of defiant freedom of expression, of transgressive sexuality, of racial typing, the idealization of males, or even extensions into the general theme of anxiety and psychological stress. All of these are possible “topics” associated with the “subject” of the work of art. In the case of a sculpture, it is easier to return from such thematic excurses and stick strictly to formal matters of craft; it is easier with the David to perceive the important central fact that the final artistic product is materially identical to the rough-hewn block of marble that was the artist’s starting point. Among sculptors, such craft-consciousness is all-important. What is the formal equivalent to this simple craft perception in playwriting?

For a playwright, the formal equivalent to Michelangelo’s huge block of stone – the “raw material” delivered into his hands before he started his formal work – is a chunk of time: say an hour or two of raw, unfashioned time. Three hours is an outer limit verging on too much, and 4 hours is categorically too large a unit for a contemporary playwright to work with. This medium (i.e., time) is a very difficult medium in which to compose formal structures. How do you “carve” up time into artistic forms? You do so through the time-arts of rhythm, tempo, duration, repetition, variation, legato, staccato, etc. These shapings of time units are very far removed – conceptually– from stories and their typical thematic preoccupations and associations. The shapes given to succeeding segments of time (durations) are properly referred to as the plot of a play. Aristotle elaborated in The Poetics that what he meant by the plot (μυθος) was “the arrangement of the incidents” (σύνθεσιν των πραγμάτων), (Poetics 1450a, 4–5, in Butcher and Aristotle, 1951, p. 24) and I follow his usage here.

Most people, when asked about the plot of a play (which should start them thinking about a time-form) will start retelling the story they gathered from attending or reading the play. Asked to describe the plot, most people will fill us in on what they remember the play to have been about. But “plot” is properly reserved to describe the temporal form of the play, and developing the habit of perceiving the difference between plot and story, or time-form and story “content” is the quickest way to develop serious artistic consciousness in the theatre. The formal issue is complicated by the simple fact that most people who love the theatre are attracted by what the theatre portrays (just as Michelangelo is widely appreciated for his “lifelike” stone forms), and only secondarily by how the theatre managed the portrayal of its so-called “content.” Form is the most important artistic aspect of the work of composition, and “content” is only the pretext for building an artistic form – be it a stone-form in sculpture or a plot-form in the theatre.

Time: the medium of the theatre

Since no play, in whatever style it was conceived, has ever escaped the necessity of unfolding in time, we can repeat Aristotle’s ancient formal observation with reasonable confidence in its continued relevance: all plays necessarily have a discernible beginning, middle, and end. The defining time-medium is more intuitively obvious in the case of music and dance than it is in the theatre, where time-awareness is intentionally upstaged by spectacle. We will want, in practice, to continue to dazzle our audiences, but at some stage in training, theatre practitioners need to achieve active consciousness of their time-awareness. A simple way to grasp the difference is to consider how hard theatre artists work to assure that audiences are never “time-free” during a live performance. They are exposed to a relentlessly unfolding event in time – in fact it is common practice in the theatre to “push” the audience, to force-feed them at a pace that leaves them no leeway to wonder about other things, or wander in their own thoughts. There is a curious passage in Dante’s Purgatorio that is relevant here. In Canto IV (line 10), the poet speaks of himself as losing track of time, and he muses on “[la] potenza … che l’ascolta” – the faculty that “listens to” time. As theatre artists, we generally want complete control over the audience’s “time-sense,” or their faculty to perceive time itself as a medium. We are failing when they start looking at their watches. It is worthwhile pausing to consider what this “time faculty” is, and what it is that it is keeping track of.

Time is notoriously difficult to define. We might all agree with Saint Augustine, who left us in Book XI of his Confessions some of the best ruminations on time in our literature. He observed, “I know well enough what [time] is, provided that nobody asks me; but if I am asked what it is and try to explain, I am baffled” (Pine-Coffin and Saint Augustine, 1961, p. 264). Upon further reflection, Augustine noticed how long it was taking him to think through what time might be: “I have been talking of time for a long time, and this long time would not be a long time unless time had passed” (Sheed and Saint Augustine, 1943, p. 280). As still more time passed, Augustine puzzled on this intractably tautological quandary until he broke through to one of our most valuable insights about time perception:

… it is not the future that is long, for the future does not exist: a long future is merely a long expectation of the future; nor is the past long since the past does not exist: a long past is merely a long memory of the past.…. The mind expects, attends and remembers: what it expects passes, by way of what it attends to, into what it remembers.

(Ibid., p. 284)

And this observation is as good a description of the medium of the drama as any I have found anywhere. When we build dramatic performance “structures” out of time, we are building a sequence of durations, and these consist of effects attended to (by the audience) as they occur, then expectations born from these witnessed effects, and gradually an accumulating remembrance of the whole sequence – the “form” we properly call the “plot” of the play. In a good play, the time-sequence adds up to a memorable, distinguishable whole, with a clear beginning, a compelling middle, and a decisive and emphatic end.

Once we think of audiences using their memory and their innate “time-empathy” to “follow” and anticipate the course of a performance, we are thinking as a playwright or a director should. In the theatre, we make our artifacts primarily out of ongoing “units” of time. We contrive our packets of duration such that audiences are swept along by a time-form that is, we hope, under our artistic control. Audiences cannot stop the show for a second pass (unless we stage it such that they must); they do not have the freedom of another look, or a double-take with redoubled concentration. And this is the deepest principle of form in the drama. What you do with your time-form determines the style in which you practice. Robert Wilson, for instance, structures a great deal of extra time for audience reflection into his performances. That “extra” time is part of his plot. He also provides many occasions for a second look by re-staging recurrent motifs and figures. Because such staging breaks the by-now conventionally fast pace of performance, many people have found Wilson’s stagings baffling at first sight, and “slow.” But many who have secretly resented the coercion and artificiality of conventional staging have felt relieved and liberated attending Wilson’s works. He has certainly freed them of the metronomic “ping-pong” exchange of conventional dialogue – something that alienates many people from the conventional theatre. He has also returned some of the freedom a coercive time-form curtails, letting the audience see – literally – in the “time-less” way Lessing described the experience of a viewer in an art gallery.

Duration

Duration is a word that describes the essentially psychological phenomenon isolated by Augustine: our innate ability to perceive passages of time as somehow “entities,” something separable and portable (in our minds) as a “thing,” a unit. The word “duration” is the name of this psychological experience of time. It contrasts, for instance, with the scientific postula...