This is a test

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Genetics and its related technologies are revolutionizing the world. The media is regularly dominated by controversy over the latest genetically modified (GM) food, human gene therapy or cancer chip technology. Maverick scientists are in the process of cloning humans, and the human genome sequence is available on the Internet. Fifty years ago we di

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Terrible Beauty is Born by Brendan Curran in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Teoría, práctica y referencia médicas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Uniquely similar! | 1 |

You, dear reader, are unique. Nobody who has ever lived, or will ever live, is quite like you. Nobody will ever look exactly like you, think exactly like you, see the world with your eyes, hear the world with your ears, write with handwriting that is quite like yours or indeed leave the same fingerprints as you do. And yet you, I, and everyone who has ever lived, are indistinguishable from one another in so many ways:

• we each began our lives as a single fertilised egg that became implanted in our mother’s womb;

• a foetus developed and a new baby was born;

• helpless at first, but rapidly learning how to cope with the outside world, the baby became a young child, reached puberty and developed into a sexually mature individual who was then ready to start the life cycle of the next generation.

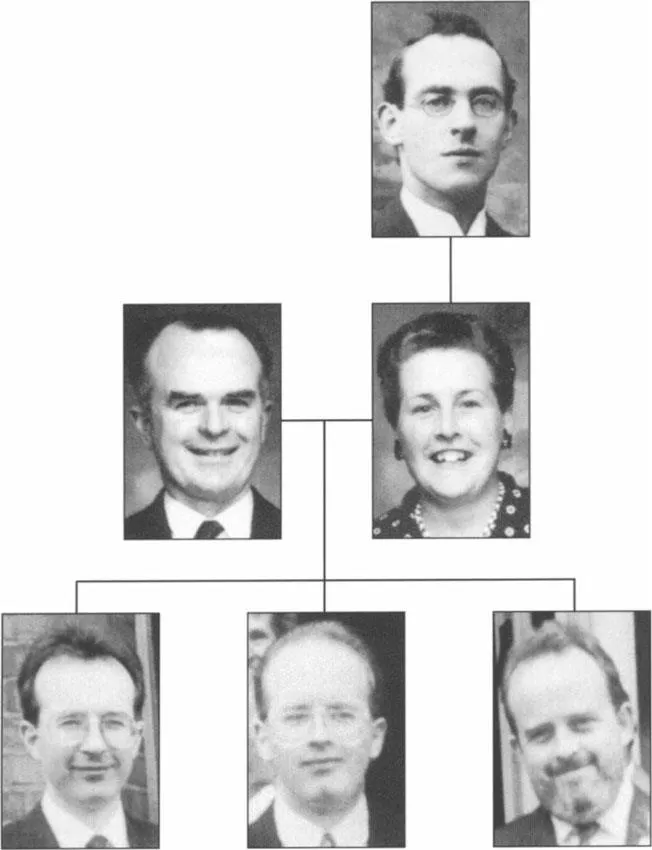

All our similarities notwithstanding, we are instantly distinguishable from one another and even from our closest relatives. I have a bump on my nose that I inherited from my father and short-sightedness that came from my maternal grandfather. My older brother looks like me (although he is by no means as handsome of course!). As his embarrassed girlfriends will tell you, my voice sounds identical to that of my younger brother over the telephone, yet be bears little physical resemblance to either of his two better-looking brothers (Figure 1.1). He has nevertheless an identical build to that of a paternal first cousin. His face may well resemble that of our mother but it is difficult to judge as she does not wear a beard. Suffice to say that clones we three are not!

But anyone who is reading this book might well be a clone; for every 350 readers, one will be. You will be physically almost indistinguishable from your brother (if you are a male) or sister (if you are a female). You will have similar likes and dislikes, taste in clothes and toiletries, be good at the same type of subject in school and probably even play the same sort of sport. Yet you will lead totally separate lives. Yes, human clones have existed ever since nature designed a system that sometimes produces identical twins.

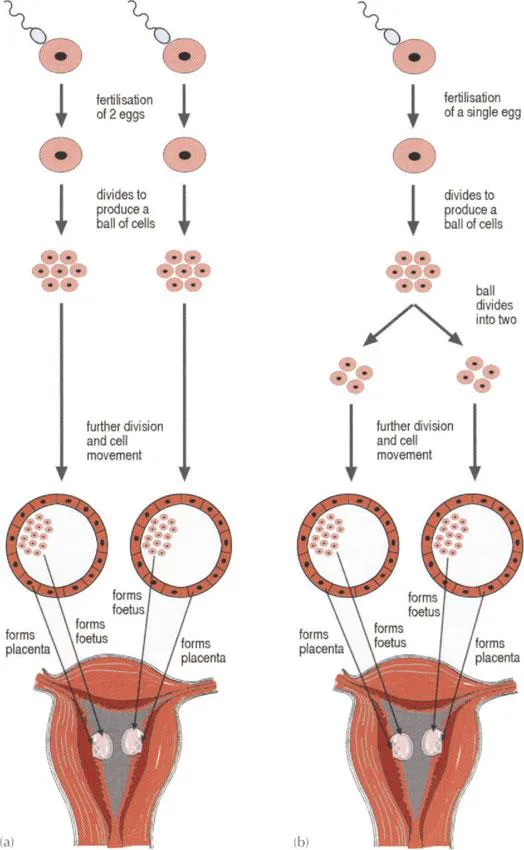

All humans begin life when a sperm cell from their father fuses with an egg cell from their mother. Non-identical twins arise when two different sperms fuse with two separate eggs at the same time, resulting in two offspring (Figure 1.2a). These are as dissimilar as any singly conceived individuals and, indeed, are frequently of different sex. Human clones (identical twins) arise when a single fertilised egg divides to produce two cells, each one of which develops to produce a new individual (Figure 1.2b). United at conception, divided shortly afterwards, born as two independent individuals, these offspring are clones of one another. Animal clones of all shapes and sizes have existed for millennia, so why was there such a fuss when a cloned lamb called Dolly was born in 1997?

A clone with a difference

The birth of Dolly (Figure 1.3) heralded a revolution in reproductive technology because she did not have a genetic mother or father but was instead ‘propagated’ by taking a piece of one sheep and treating it in such a way that it grew into a new identical animal. Strictly speaking, Dolly fails to fulfil any of the criteria for normal clones. She had no father, she was not conceived and (if you excluded the massed ranks of media vultures) Dolly was born alone. Impossible though it may seem, the animal with whom Dolly is identical is not her sister but her mother. Here we have a clone with a difference – not produced as the result of a fertilised egg splitting to generate two separate individuals but by scientists taking an individual breast cell from a mature sheep and using biological tricks to grow a completely new identical animal from it. Rarely has a biological experiment been met with such hysteria from the press and genuine interest from the public at large who asked seriously:

• Why bother doing it?

• How does it work?

• Are human clones next?

A brief history of sex

For thousands of years, the collective wisdom on reproduction held that the female womb was a specialised environment to nourish and support the growth of a miniature baby implanted in it by the male sperm. Hence the biblical references to male ‘seed’ and ‘barren womb’ – analogies to plant horticulture which were well known at the time. This theory had many short-comings, not least of which were:

• Why were the offspring not all identical males?

• How did females arise?

• And how come that the offspring (male and female alike) often resembled their mother?

The predominately male thinkers of early history had little difficulty with these shortcomings. Not surprisingly, later thinkers abandoned the theory of a pre-packaged human planted in ‘fertile soil’ for one in which males and females managed to co-operate and share in transmitting the information needed to construct a new human being.

It was an obvious step but by no means an easy solution. Let us suppose that the egg contains a copy of the information needed to construct an animal identical with its mother while the male sperm possesses the information for making an individual exactly like its father. Combining the two would produce an offspring carrying all of the information from both parents; it would have to be of both sexes and identical in all respects to all its siblings. Of course, neither of these things is actually true.

Even more impossibly, as each generation passed, progeny would accumulate twice the information content of their parents. Quite apart from the increasing burden of coping with so much data that the successive generations of progeny would contain, the fact that the original parents were viable with only the original amount of information testifies to the uselessness of multiple copies! No; somehow, not all of the information from both parents gets passed to their offspring.

As two individuals are involved in each act of conception, it makes sense to suggest that each contributes half of the information needed to assemble a new individual. But this, of course, cannot be the case because if it occurred at random, some progeny would have two noses and the other none, three ears versus one eye, etc. while if it took place in an organised fashion (e.g. nose from mother, eyes from father, and so on), all of the progeny would be identical with one another – each would have mother’s nose, father’s eyes and no other combination of characteristics would be possible.

No, nature has designed a much more subtle, foolproof system to allow each individual to exhibit traits that are different from both of its parents and all of its siblings. The same arrangement also prevents even a slight increase in the total amount of genetic information passed on from one generation to the next.

The solution is extremely elegant

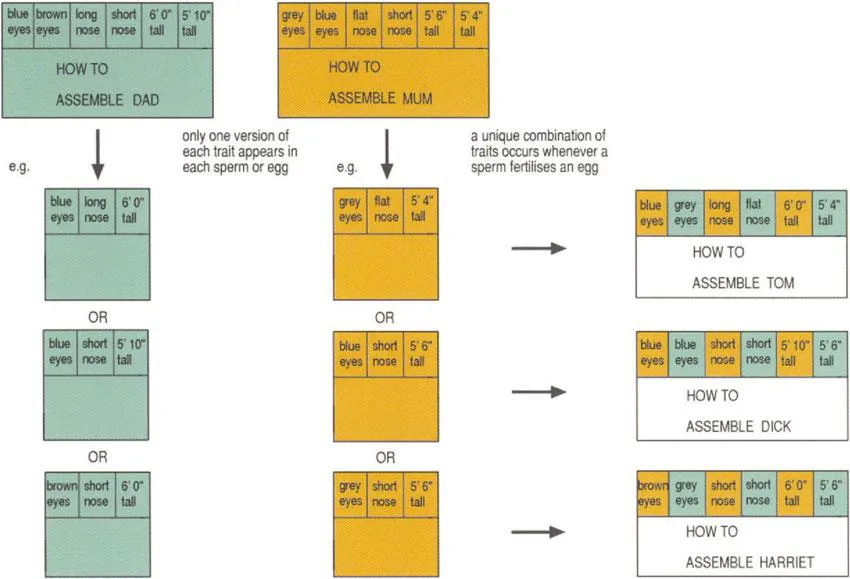

Nature ensures that the information for each and every trait is inherited from both parents, thus ensuring that two copies of the recipe for each trait exist in their offspring. When the offspring themselves reproduce, nature provides a mechanism which again ensures that only one copy for each trait is passed on to the next generation (Figure 1.4). Even neater is the fact that the complete recipe for the animal passed on to the next generation is a random mixture of the two recipes in each of the parents. Such a random mixture from both parents generates unique individual progeny.

It is all done with sex – such a neat little trick that it is found throughout nature and for a very good reason. The genetic diversity that sex generates confers flexibility on the population as a whole by allowing it to adapt to changes in the environment; continual novelty among offspring makes it more likely that, even if the environment does change, some individuals will be able to cope and produce their own young. Animal breeders are familiar with this phenomenon. Few of the pioneers who bred wolves for use as domestic animals could have foreseen the resultant diversity of dog breeds available today. The genetic variation and flexibility found in the original wolf population has, through inbreeding, been channelled to generate different types of dog. Each type on its own constitutes a less varied, less flexible population of individuals – it is difficult to imagine breeding miniature poodles until they produced an Irish Wolfhound! The offspring from a cross between those types of dog would carry much more genetic variation than either of the parents and would almost certainly possess attributes shown by neither its mother or its father.

The problem with sex

Sex is designed to generate diversity, at which it is extremely good. Being unique might be very desirable for mankind but, for humans whose life’s work is to breed prize herds of cattle, sheep and horses, the lottery of inherited traits that occurs every time an egg and sperm fuse is the last thing they desire. Inbred animals might all look very similar but there is still genetic variation within each individual breed – sufficient for an animal breeder to spend a lifetime breeding them for a uniquely desirable combination of traits. The offspring of a prize animal is rarely if ever as distinguished as its parents because it inherits only half its genetic information from its prize-winning mother or father. The other half comes from the second parent, and the same genetic lottery that gave rise to the unique combination of genes in the parent generates new diversity in the progeny. Even breeding from two prize-winning parents may not do the trick because the way the characteristics from each parent show themselves in the presence of the other is often highly unpredictable.

Quite simply, sexual reproduction will fail to produce uniform offspring. If, instead of relying on it, a magic wand could be waved over a prize dog to cause it to divide into ten new identical dogs, the problems caused by the lottery due to sexual reproduction would be avoided. The birth of Dolly the sheep shows that such a magic wand is now at hand.

No sex please – we’re clones!

The word ‘clone’ is often associated with images from memorable science fiction movies where deranged scientists in darkened laboratories carry out sinister goings on. There is no doubt that ‘real scientists’ produce and work with a range of different types of clones, but nothing like the variety that nature herself generates.

The word ‘clone’ refers to one or more individuals that share identical genetic material. Clones abound in nature and, in fact, have been produced by a large section of the ‘lay’ population who have never darkened the door of a laboratory. Anyone who has grown an ‘adult’ plant from a spider-plant plantlet is a cloner! Propagating any plant from a cutting produces identical individuals – hence clones. But plants do not need man to help – strawberries (and many other plants) produce runners giving rise to new plants which are clones of the original. ‘I must have a cutting!’ is synonymous with ‘I would like to have a plant identical in every way to the one you have!’ There isn’t a gardener in the country who has not cloned some plant or other.

But clones are not restricted to plants in nature. The many yeast strains used to produce different types of beer are examples of yeast cell clones. The E. coli outbreak in Scotland in 1997 was caused by a particular strain of bacteria, an example of a bacterial clone. The different strains of influenza virus are examples of viral clones, each one requiring a separate vaccine. A single cancer cell can produce a tumour which is a ball of identical cells – clones of the original. Clones are simply a group of individuals possessing identical genetic information. The majority of naturally occurring clones arise without any need of sex, but animal clones occur in nature only as identical twins (or multiple births) who began their life journey as one single fertilised egg which divided to give separate and independent individuals at birth. Animal clones are special because they are the direct result of sexual reproduction; all the clones of plants or microbes come from simple cell division and continued growth as new individuals.

Sex produces diversity; clones produce uniformity. Nature values both but, on balance, prefers sex. Mankind may enjoy the latter but on balance prefers clones when it comes to earni...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Uniquely similar!

- Chapter 2 Incredible journeys

- Chapter 3 What is it about the nucleus?

- Chapter 4 The health of the nation

- Chapter 5 Dealing with the invisible

- Chapter 6 Awesome analysis

- Chapter 7 Knowledge is power

- Chapter 8 Marvellous molecules

- Chapter 9 Wonderful cures

- Chapter 10 Amazing ambitions

- Chapter 11 All is changed – changed utterly

- Epilogue

- Index