This is a test

- 170 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Theory and Reality of International Politics

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1998, this volume deals with the explanation of international politics and foreign policy. Levels of explanation and their interrelationships offer the book's structure. Based on critiques of major IR approaches, a 'bottom-up' instead of a systemic 'top-down' perspective (Waltz) is advocated, but without falling prey to reductionism explaining international politics from domestic factors. Explanation of state behaviour should primarily stress states' salient environment, but occasionally also their historical lessons from previous experience with this environment. International organizations or other non-state actors may be allowed an influence of their own in certain areas, but the state remains in ultimate control.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Theory and Reality of International Politics by Hans Mouritzen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Molecules in a gas or consumers in a market are mobile; there is no specific and stable environment for each unit. After some drifting around in various segments and corners of the system, the 'average environment' of each unit can be equated with the system, it forms part of: the gas or the market. In this sense all units face the same environment. By contrast, nation-states in international politics are mutually non-mobile; this is an implicit, but fundamental property of international politics on a par with its anarchy. Non-mobility means that each state faces a specific and stable salient environment rather than the international system as a whole. Since power and incentive wane with distance, it follows that each state's salient environment will have significant explanatory power in relation to its behaviour (foreign policy). However, most of the academic international relations (IR) discipline proceeds, as if states were mobile like floating vessels in the sea with no specific environment. It has been discussed to the brink of boredom in IR, whether 'systemic' or 'domestic' factors can explain foreign policy and international politics, but states' salient environment is apparently forgotten. It is puzzling why this repression has taken place in the IR community unlike among historians or journalists, for instance. One reason is probably that theoretical constructs have been uncritically imported from branches of science studying systems of mobile units (economics and cybernetics, for instance). Also, IR as a relatively young discipline desiring scientific respectability may have felt that its comprehensive object of study - the international system - should be somehow 'important' and therefore carry a reasonable explanatory power of its own. In this way, however, it has become a straitjacket for theoretical development.

Post-bipolarity has made regional and local power structures more important at the expense of an overall systemic structure. This may explain the renewed interest in geo-politics, for instance. It is too superficial to say, however, that the current systemic polarity requires other theories than did bipolarity. As I shall argue, post-bipolarity makes certain enduring peculiarities of international politics more visible than they were during bipolarity, but the point is that they have been there all the time.

International organizations or other non-state actors may be allowed an influence of their own in certain areas, but the state remains in ultimate control. Likewise, internal factors may sometimes be permitted an influence on foreign policy, but states' salient environment is ascribed explanatory primacy in this book. The conception of international politics offered here invites a bottom-up instead of a systemic top-down perspective, but without falling prey to reductionism (explaining international politics from internal factors, mainly). Explanation of state behaviour should be made primarily on the basis of states' respective salient environments - that tend to vary considerably from state to state.

All this is about segments of reality: I assume reality existing independently from our language and theories about it. This disentanglement of theory and reality makes a confrontation between the two a meaningful enterprise; through this, it should be possible to learn that one theory is better than another. We avoid relativism, i.e. of the form 'you can have your paradigm, theories, and assumptions, and we can have ours'. 'Theory' is understood here in a non-puristic sense as a set of interrelated assertions about reality, from which empirically testable expectations can be derived. The assertions have common underlying reasonings with their own independent justification, explaining why we should believe them to be true. 'Theoretical construct' is a wider concept, covering not only theories, proper, but also less developed models, hypotheses, and pre-theories. A 'pre-theory' is a construct saying, typically: 'if your object of explanation is such and such, look to a certain class of factors for a good explanation'. It also provides reasons, why we should look in that particular direction. In this book, two pre-theories are established: one about the importance of units' salient environment at the expense of systemic explanation for understanding international politics, and one indicating the nature of the interplay between salient environment and internal explanatory factors. Within the 'action space' provided by these pre-theories, specific theories are formulated and tested.

Chapter 2 presents the non-mobility argument, along with some modifications to it (keeping the door ajar for systemic explanation under special circumstances). Chapter 3 surveys the IR literature on explanatory levels and demonstrates the shading of the environment level taking place here. The systemic theory of Kenneth Waltz as well as the reductionist approaches of 'comparative foreign policy' and small state theory are critiziced on the basis of the non-mobility argument, essentially. Chapter 4 turns to a further presentation of the preferred explanatory logic and level. The notion of environment polarity instead of the usual systemic polarity is introduced and illustrated. In chapter 5, three different theories rooted in the salient environment are formulated and tested: one about tension between the strong and activity of the weak, another about balance-of-power between the strong and bandwagoning of the weak, and a third one labelled a 'twin distance model'. In empirical terms, it explains the five Nordic countries' respective Baltic engagements on the basis of their geographical distances from the Soviet Union/Russia and from the Baltic Sea region. In chapters 6 and 7, we climb down the level ladder - only to conclude that the salient environment should be ascribed primacy in relation to internal explanatory factors. Two illustrations of external/internal interplay are offered: 1) alliance policy in the Baltic Sea rim space, in which foreign policy heritages are added to basic geopolitical factors, and 2) bandwagoning in the face of a pole of attraction (the European Union), where all kinds of domestic factors are added to (but subsidiary to) the European polarity restrictions. Even though a state-centric conception of international politics prevails in this book, chapter 8 investigates theoretically and empirically the precise nature of this state-centrism in relation to international governmental organizations (IGOs) and the EU. The latter entity necessitates that we relate to prevalent theories of regional integration. Methodology should preferably be post-hoc, i.e. reflection on some presented theoretical construct rather than an apriori credo. This unavoidably lends it a certain pharisaical flavour that the reader will have to endure (chapter 9). Whereas discussion of IR school belongingness is hardly fruitful for constructive purposes, the philosophy of science school of critical rationalism has served as a guideline for the present book. That is made explicit in this final chapter.

2 The Argument

The global international system has two fundamental properties: it is non-hierarchic (some would say anarchic), and its major units are mutually nonmobile. The properties are fundamental in the sense of being non-reducible to more basic ones. Only the former of these two properties has been subject to attention in IR theory, IR 'great debates', or IR textbooks. I shall argue here that this is a devastating mistake: the combination of the two properties has farreaching consequences for the kind of theories and explanations that can be fruitfully applied within the field. So whereas non-mobility in itself is a rather self-evident fact (probably the reason why it is overlooked), its implications are wideranging; they are actually at odds with mainstream developments within IR1.

Analogously to consequences deduced from the traditional assumption of international anarchy (e.g. the security dilemma, the prevalence of national security interests), the implications derived here are necessarily of a somewhat imprecise nature. They pertain to relative potencies of levels of explanation in international politics.

Levels of Explanation

I shall operate here with 'level of explanation' instead of the vague notion of 'level of analysis' - being responsible for much confusion (one reason being that 'analysis' may also encompass description and prediction apart from explanation). An explanation is the answer to a 'why-question'; the object of explanation is what puzzles us and 'requires' an explanation. The source of explanation is what explains this object. Level of explanation is the locus of this source.2

International politics is understood here as the interaction of two or more international units. In other words, negotiations between Croatia and Slovenia is as much international politics as the Cuban missile crisis, and also reactive behaviour is a form of interaction. The immediate object of explanation in the below discussion is foreign policy, that is the content of the external behaviour of nation-states3. Since nation-states are the major units of international politics, this object of explanation is difficult to disentangle from international politics as here understood.

Let us turn to the specific levels of explanation to be discussed. At the systemic level, international politics - typically its distribution of power - is viewed from a bird's eye perspective; a camera snap-shot is taken from above in order to elucidate the backcloth of nation-state behaviour. Of course, we may zoom in at a particular region, as in subsystemic analyses. The salient environment level, by contrast, entails something qualitatively different: the world - its polarity, not least - is viewed from the bottom-up perspective of the specific nation-state, whose behavior we wish to explain. The camera has been lowered to the nation-state capital in question and turned upside down. 'Environment polarity' or 'bottom up polarity' may sound like contradictions in terms, because we are used to thinking of polarity from a systemic perspective. Of course, only a segment of the world can be caught by the camera lense from this particular frog perspective. The camera analogy is crucial: I am not talking about particular decision-makers' perceptions of the salient environment; that belongs to a separate level of explanation: the decision-making level. I am talking about the salient environment of a nation-state, as it can be construed by analysts as objectively as possible, and no less objectively than systemic attributes. For instance, whereas the overall system may count as unipolar, because there is only one superpower, the salient environment of state 'X' may simultaneously be tripolar, as in addition to the superpower two local great powers have roughly the same ability to project power in relation to 'X'. Finally, there is the level of units' domestic factors: foreign policy is sought explained on the basis of party competition, the activities of domestic pressure groups, public opinion, etc.

The principle of level classification used here is the step-wise abandoning of simplifying assumptions: at the salient environment level, we abandon the systemic level assumption that all units face one and the same environment (the system); at the domestic factors' level, we abandon the assumption that units (nation-states) react similarly irrespective of subgroup competition; and at the decision-making level, we abandon the assumption that governments react similarly, irrespective of idiosyncratic factors, bureaucratic factors, or factors in the very decision-making process. What is being classified, hence, is what an explanation emphasizes as interesting or peculiar (carrying explanatory weight); however, any explanation is simultaneously based on assumptions pertaining to other levels, whether they be explicitly formulated or tacitly assumed.

International Politics: Anarchy and States' Non-Mobility

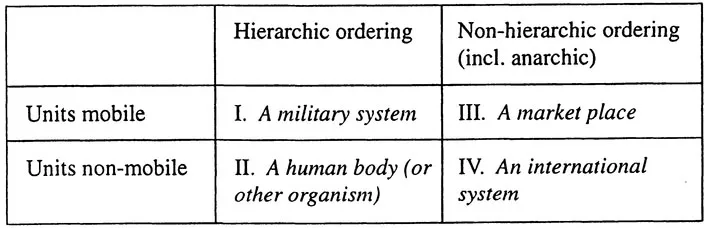

An 'international system' is defined here as a system with no relevant political environment. Through this definition, it should also encompass certain historic systems with less than global extent. Let us briefly put such a system into perspective in relation to other types of systems. In the four-fold table in fig. 2.1, we have the system's basic ordering principle along one dimension (hierarchy vs. non-hierarchy) and the mutual mobility of its units along the other dimension.

Fig. 2.1 Basic types of systems from the viewpoint of explanatory level

What levels of theorizing are likely to be fruitful for each of these types of systems? In particular, what are the prospects for systemic theorizing that explains units' behavior by pointing to attributes/developments of the system as a whole4? If the units are mobile, then each unit will face a persistently shifting environment. It will probably seek towards a beneficial environment, but so will all other units. This entails continuous adjustments of position on behalf of all units. Therefore, a unit's 'average' environment, when considered over a reasonable5 time-span, is the system as a whole - not any particular segment of it. If the units are non-mobile, by contrast6, each unit has a stable neighbourhood, consisting of a few geographically adjacent units and their mutual relationships. The environment in its essential traits typically keeps constant for whole 'eras', only to be broken off by the dissolution of neighbouring units or other dramatic events. The unit is bound to face this salient environment whether it likes it or not; it cannot drift away so as to acquaint itself with some new neighbours. The challenges it seeks or faces are likely to originate mostly from this specific environment, since power and incentive wane with distance, other things being equal; this pertains both to its own power/incentive and that of others7.

When it comes to explanation and theorizing regarding the unit's behavior, then, the crucial factors are more likely to be found in this salient environment than being attributes/developments of the system as a whole. Conversely, if the units are mobile and therefore facing no particular environment, the latter type of explanation is likely to be much more relevant (quite disregarding units' internal attrubutes, of course, that may be relevant both for mobile and non-mobile units). One can say, therefore, that units' non-mobility has introduced a cleavage between unit and system - each unit's salient environment. From the viewpoint of accounting for units' behaviour, this entails an extra explanatory level in its own right.

As should be obvious, non-mobility is different from territoriality or spatiality as such. Also movement takes place in space. Non-mobility, however, entails that certain spatial relations are frozen and made into almost permanent conditions. Also non-spatial distances may be frozen, as ideological distances between political parties in a multi-party system (e.g. Sjöblom 1968). Such parties are relatively non-mobile in relation to each other, since credibility concerns prevent them from switching place on an ideological left-to-right scale. This means that each party has a salient environment; its main concern is competition with its neighbouring parties to the right and left for voters, not least. This salient environment may be more important than attributes of the party-system as a whole for the explanation of its behaviour.

I shall only say a few words about the second dimension, as this has been subject to abundant and persistent IR attention. Obviously, a hierarchic order entails a more coherent and consciously coordinated system than an anarchic one. The actor at the apex - embodying the system - is likely to have a good deal of control over units' behaviour and will therefore provide a natural locus of explanation regarding the system's functioning. This represents one type of systemic explanation, albeit not the only one. A non-hierarchic order is likely to be more heterogeneous from the viewpoint of such overall explanation; as will be argued, some types of structures are likely to keep a looser grip on units' behaviour than others - thereby leaving more room for the role of local explanatory factors.

These two reasonings shall now be combined and applied to the illustration...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Argument

- 3 IR Theory: A Critical Evaluation

- 4 The Preferred Mode of Explanation: A Further Presentation

- 5 Testing Theories

- 6 Salient Environment and Domestic Explanatory Factors: The Nature of the Interplay

- 7 Two Illustrations of Interplay

- 8 The Role of International Organizations

- 9 Theory and Reality of International Politics

- Bibliography

- Index