eBook - ePub

Foregone Conclusions

U.s. Weapons Acquisition In The Post-cold War Transition

James H. Lebovic

This is a test

- 198 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Foregone Conclusions

U.s. Weapons Acquisition In The Post-cold War Transition

James H. Lebovic

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

With the end of the Cold War and the erosion of the Soviet threat, the United States is reevaluating its defense policy and its acquisition of weapons. James Lebovic shows that, although current military missions are adapted to post-Cold War realities, the self-defeating bias of bureaucrats and military services toward Cold War weaponry is still prevalent. He examines the impact of this bias on the armed services as they assess threat, generate requirements, develop and change weapon concepts, set production rates, and engage in testing. The author asserts that bias compromises service interests and broader military objectives and he offers general policy recommendations to put U.S. weapons acquisition on a more effective track.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Foregone Conclusions an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Foregone Conclusions by James H. Lebovic in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

U.S. Weapons Acquisition in the Post-Cold War Transition

Uncertain about the future and lacking direction, the United States faces a rapidly changing security environment. The U.S. defense community has traditionally dealt with change by offering more of the same: trimming and deferring some programs, cancelling others, while offering a budget essentially like those before it. With the end of the Cold War, it continued the practice. The U.S. downsized and restructured military forces without profoundly rethinking U.S. global strategy and tactics or reevaluating military technology. The U.S. was left with a narrow set of bureaucratically prescribed options.

During the Cold War, the service-dominated acquisition system fostered widespread duplication in weapons, to the chagrin of defense reformers. Congress launched reform initiatives such as the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 and more recent, less formal challenges to service duplication by the Senate Committee on Armed Services. Largely responding to outside efforts, the military accepted joint weapon development and procurement, unified commands, strengthened centralized control by creating the position of undersecretary of defense for acquisition, enhanced the powers of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), created the position of JCS vice chairman with duties that include chairing a newly formed Joint Requirements Oversight Council (for limiting program duplication and ensuring adequate resources among the services),1 and undertook high-level analyses of post-Cold War service roles and missions. Yet the services still managed to do things the old way. Joint acquisition was rejected due to service mission "peculiarities," the unified commands still could not overcome interservice barriers to communication and information exchange during the Gulf War, undersecretaries for acquisition resigned in disgust or under fire, and Pentagon officials relied on service-generated analyses that spoke little to overlapping service missions. The services recognized the need for integration in the high-speed, mobile, and deadly wars of the future but also held to the past.

The end of the Cold War magnified problems that long bedeviled acquisition. During the Cold War, the military pursued technology of dubious value and refused to reassess primary program commitments. In the post-Cold War period, it continued these practices. The navy, army, and air force clung to traditional missions and associated state-of-the-art technology — the aircraft carrier, tank, and penetrating bomber and air superiority fighter, respectively. They pushed their preferences through review processes that were largely cautious and consensual. The most prominent among them was the so-called "Bottom-Up Review" of the Clinton administration. It recommended terminating some high-profile weapon programs — including the navy AX stealth attack plane (more recently dubbed the A/F-X) and the air force/navy Multirole Fighter — while supporting other controversial ones — the air force Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF), the navy F/A-18 stealth upgrade (the E/F), and the army Comanche stealth (or light) helicopter.

In explaining the role and behavior of the services, a strategic view of bureaucratic politics is the conventional wisdom.2 The strategic view reduces policies, budgets, and programs to tactical moves, coalitions, and compromises. It explains behavior and solves puzzles by examining service interests and relative capabilities within accepted "action channels." Bureaucratic strategy is reputed to dominate acquisition throughout,3 as weapons are initiated and shaped through rivalry. The military services (and subservices) are key acquisition competitors and use weapons to stake claims, acquire resources, and affirm key missions. (Congress, Pentagon officials, the White House, and defense contracting firms also compete, though not, strictly speaking, "bureaucratic" competitors.) The services bargain with other players, form coalitions, control information, and manipulate the acquisition process to obtain key weapons. They engineer threats, strategically choose requirements, limit oversight, select and distort data, and skip and collapse acquisition stages to create political momentum and proscribe less desired alternatives. For as long as possible, they perpetuate the myth that a weapon is required, on schedule, and is progressing as planned. The day of reckoning might come, when requirements are found to be overstated and performance and/or cost targets are shown not to have been met. At that point, the political package can unravel. Critics will join forces, supportive alliances will form again, and new political opportunities could be presented. Still, weapon proponents can prevail. With a financial commitment, a weapon becomes less costly than alternatives, and, ironically, alternatives can be hurt by the fear that any new program, like the current one, will develop beyond control.

While presenting an unflattering picture of policymaking, the strategic view is not entirely pessimistic on whether bureaucracies can adapt to changing global realities or pursue broader national objectives. Service defenders note that the services have won wars, pursue military (as much as political) objectives, learn from mistakes and adapt to change, commit the pardonable sin of acquiring too much capability (allowing a hedge against risk), adjust their priorities when given needed resources, and compromise and cooperate to accomplish interservice objectives when necessary.

But bureaucratic politics actually has two faces — one rational and, the other, nonrational. Observers cannot be as sanguine about the future when acknowledging the nonrational influence of bureaucratic bias. With its effects, the services pursue weapons as if they sufficiently promote service interests and necessarily accomplish broader military objectives. The services sidestep or subordinate weapon requirements to existing missions, associated weapons, or available technology; and they surrender control of development and production by freely adjusting program performance, schedules, and cost. The services might indeed be strategists who attempt to engineer acquisition to advantage; but they are deficient strategists. They defer to the known, familiar, and tangible and end up compromising service interests and broad military objectives.

Such failings have long concerned acquisition critics. Critics argue that weapons are procured despite unclear or unsound justifications, available substitutes, and lower-than-expected performance and higher-than-expected cost. But they rarely offer coherent and comprehensive critiques. Instead, they attribute problems to specific acquisition deficiences. These include artificial "threats," insufficient attention to available alternatives, the neglect of requirements, inattention to trade-offs in development, abuse of cost-reimbursement contracts, lack of competition, overreliance on computer analyses, inadequate weapon tests, production "concurrency" and "stretchouts," inadequate and inefficient program management, and economic and electoral interests. They also define problems to serve single, often-easy solutions. These include, more competition, less micromanagement, more realistic budgets, fixed-price contracts, and so forth. In short, critics do not fully comprehend the detrimental acquisition effects of bureaucratic strategy and bias. As a result, a bias towards technology is too often treated as a secondary force that is felt "around the edges" of bureaucratic politics.

This book counters these practices by examining the distinct, though overlapping, impacts of two converging bureaucratic political forces. While bureaucratic politics is now the dominant explanation for the failings of military acquisition, this book reveals that such politics operate in ways that are not fully appreciated, as they shape weapons, at every acquisition stage, through a profound performance bias.

This book follows bureaucratic strategy and bias through the acquisition process in offering a service-centered critique of U.S. acquisition policy. It shows the effects of strategy and bias throughout acquisition.

Chapter 2 presents the two different perspectives on the deficiencies of the acquisition process. It discusses the limits of the prevailing "strategic" view and then proposes greater scrutiny of nonrational influences that are associated, here, with "bias."

Chapter 3 shows " threats" to be bound to service strategy and bias. While bureaucratic strategy involves threats that are contrived and self-interested, bureaucratic bias implicates threats that are products of performance-oriented defense models. The chapter shows the services allowing performance to color broader military objectives.

Chapter 4 shows weapon requirements or conceptions of "need" to be products of bureaucratic strategy and bias. While bureaucratic strategy shows that the services devise requirements to bolster key missions and to defend against rival service encroachments, bureaucratic bias shows that the services fail to appreciate performance trade-offs and pursue performance at the expense of military objectives. It concludes by examining the impact of strategy and bias on a number of critical, contemporary policy issues — sea versus land-based aircraft, close air support, stealth systems, and strategic nuclear acquisition.

Chapter 5 shows service learning to be bound to a performance bias. Accordingly, it critically examines the so-called "lessons" of Desert Storm and then reflects on them with "regional conflict" experience from Somalia and Bosnia. The chapter again shows the services permitting performance to dominate military objectives.

Chapter 6 examines weapon concept development, where requirements yield to weapon specifications. While the bureaucratic strategy view implies that development is politically controlled and technically nonproblematic, a performance-bias perspective shows performance to be privileged in development and pursued without regard for consequences, such as cost. Accordingly, the chapter examines three crucial issues in weapon development and production. It, first, reveals deficiences in assessing tradeoffs in weapon performance and in cost. Second, it examines the mismanagement of acquisition timing (as related to controversial practices such as concurrency and stretchouts). And, third, it examines weapon testing, the supposed gatekeeper of acquisition.

Chapter 7 presents the acquisition context in which service strategies and biases are pursued. It, first, assesses the commercial context. It challenges the conventional wisdom that firms "buy in" to contracts. It does so by exploring two critical aspects of the commercial context — competition and contracting. It, second, assesses the acquisition role of Congress by challenging the assumption that legislators are captives of parochial economic interest. And third, it assesses the formal Defense Department acquisition (milestone) process and the involvement of the military services.

Chapter 8 summarizes the contribution of bureaucratic strategy and bias in explaining the failings of acquisition. It discusses recent efforts to manage acquisition and offers general policy recommendations.

2

Perspectives on Acquisition Deficiencies

The strategic view of bureaucratic politics offers a stark vision of self-interested policymaking. In this, it is much like contemporary realism which asserts that conflict among states is an inevitable feature of an anarchic world (because gains for one state affect the relative capabilities of others). From a strategic view, the services place their survival and desire for influence and resources above all else. Most certainly, bureaucratic strategy differs from its state counterpart. For one thing, bureaucratic sovereignty is not absolute. The services are bound by the laws, agreements, and precedents that establish an interservice division-of-labor (so-called "roles and missions") and elaborate the procedures of the formal defense planning, programming, and budgeting process. Still, the services derive power from those institutions and can use formal procedures to advantage. The result is that bureaucratic rivalry is actually more fluid and complex than interstate competition.

The popularity of the strategic view reflects a common tendency to search for culprits in diagnosing social, economic, and political problems and to draw from the obvious and the sensational, in memoirs, news accounts, and case studies of great decisions. But the problems of acquisition run deeper than revealed by a study of interests and players. The strategic view actually withers under scrutiny. As this chapter argues, the strategic view embraces vague and contradictory assertions and does not entirely square with evidence. Tire evidence instead implicates an overreliance on weapon performance criteria and opportunities as a principal source of acquisition problems.

The Limits of a Strategic Perspective

With its broad and compelling indictment of defense policymaking, the strategic perspective is an elusive foe. It maintains prominence because of what it says and because of what it does not say In the silence, it fails to question assumptions made about the motives and objectives of participants.

Questions about Motives

The strategic view of bureaucratic politics generally ignores actor motives. Sometimes, the services are shown coveting the missions of others, unable to live by agreements, and seeking to increase their resource share; and othertimes, the services are shown rejecting new missions, desiring to compromise, and willing to accept their existing share of the resource pie. Of course, under the right conditions, the services can fit any of these descriptions without creating inconsistencies. Bureaucratic actors cooperate through alliances in times of conflict, they retreat when necessary though expansionist, and so forth. Still, the literature on the subject suffers by not revealing what the services seek or why and when they seek it.

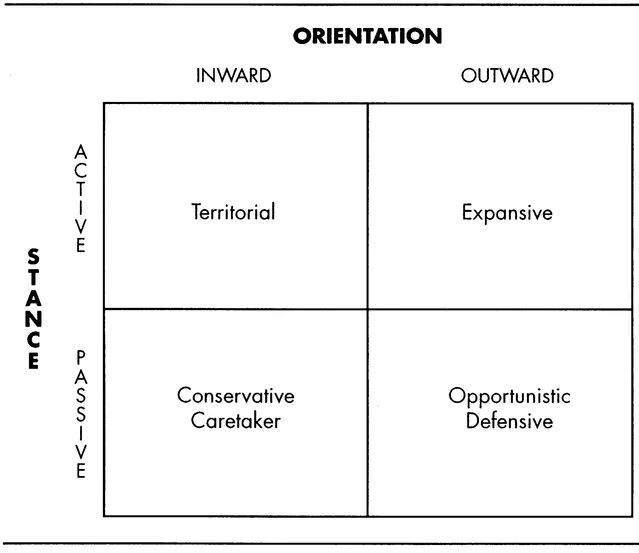

FIGURE 2.1: Bureaucratic Political Motives

As Figure 2.1 illustrates, the literature suggests four possible bureaucratic personality types. These are jointly determined by whether the services are "active" or "passive" in stance and "inward" or "outward" in orientation. The bureaucratic politics literature provides little basis for choosing among these types. It does not reveal whether or when the services seek to extend gains (an active stance) or to preserve them (a reactive one). Nor does it reveal whether or when the services seek to maintain existing missions (an inward orientation) or to augment them (an outward one). Stance does not determine orientation: if active, the services can be territorial or expansive; and, if reactive, the services can conservatively resist change or acquire new missions only when protecting older ones or handed opportunities (filling a vacuum).

Although often regarded as expansive, and thus politically combative, the services (and subservices) generally act without conflict. They accept their place within a defined divison of labor, sacrifice autonomy to serve joint doctrine, integrate weapon requirements in multiservice weapon programs, and ignore opportunities to obtain lucrative missions or to renounce unappealing ones. They actually behave in ways that are predicted by a growing literature in international politics on cooperation: under the right conditions, an active service can be passive, an outward directed service can turn inward, and so on.

First, rivals can cooperate when defining their interests in "absolute" rather than "relative" terms. The services will not conflict if they value a gain for its own sake rather than for its favorable impact on interservice capability balances. The services, then, might seek higher budgets to better do their jobs rather than to increase the service resource share. Admittedly, relative gains determine absolute ones when the size of the resource pie is fixed below levels that satisfy all recipients. The services might thus compete when budget ceilings are imposed and, more so, when lowered. Still, competition need not end cooperation. Research suggests that competitors can cooperate when willing to set aside present for future gains, when options exist that will produce mutual gain, and when allowed or required to negotiate again with the opponent (the so-called "iterated" game).1

Second, rivals can cooperate (or avoid confli...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- 1 U.S. Weapons Acquisition in the Post-Cold War Transition

- 2 Perspectives on Acquisition Deficiencies

- 3 Threat Assessment: How the Services Define Objectives

- 4 Weapon Requirements: Whether the Services Fully Consider Objectives

- 5 Organizational Learning: How the Services Change Objectives

- 6 Trade-offs, Timing, and Testing: Weapon Performance in Development and Production

- 7 Contractors, Civilians, and Congress: The Acquisition Context

- 8 Foregoing Premature Conclusions: Opening the Acquisition Process

- Notes

- Index

- About the Book and Author

Citation styles for Foregone Conclusions

APA 6 Citation

Lebovic, J. (2019). Foregone Conclusions (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1503809/foregone-conclusions-us-weapons-acquisition-in-the-postcold-war-transition-pdf (Original work published 2019)

Chicago Citation

Lebovic, James. (2019) 2019. Foregone Conclusions. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1503809/foregone-conclusions-us-weapons-acquisition-in-the-postcold-war-transition-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Lebovic, J. (2019) Foregone Conclusions. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1503809/foregone-conclusions-us-weapons-acquisition-in-the-postcold-war-transition-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Lebovic, James. Foregone Conclusions. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2019. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.