This is a test

- 326 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book explores some of the possibilities and limitations inherent in collectivization by examining agricultural changes in one Hungarian village, Pecsely in which the transition from traditional peasant existence to a socialist society and collectivized agriculture could be traced.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Beyond The Plan by Ildiko Vasary in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Antecedents

1

The Three Villages in the Valley

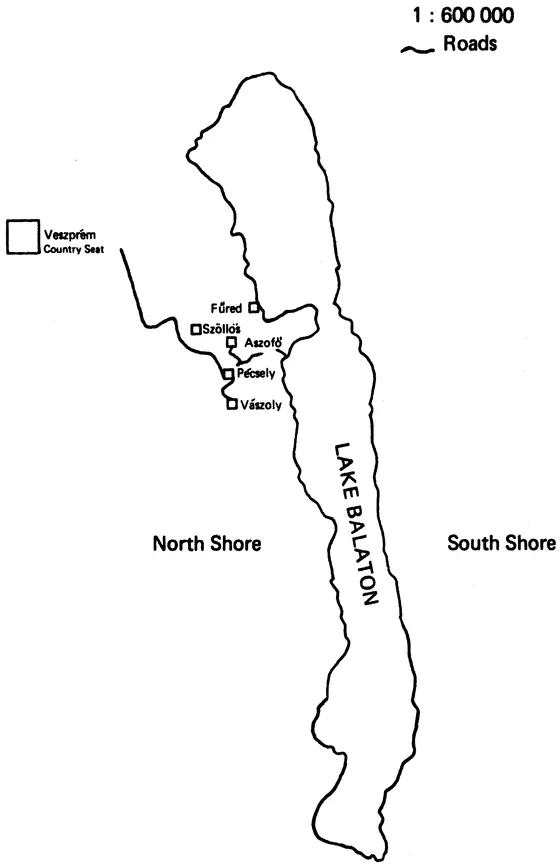

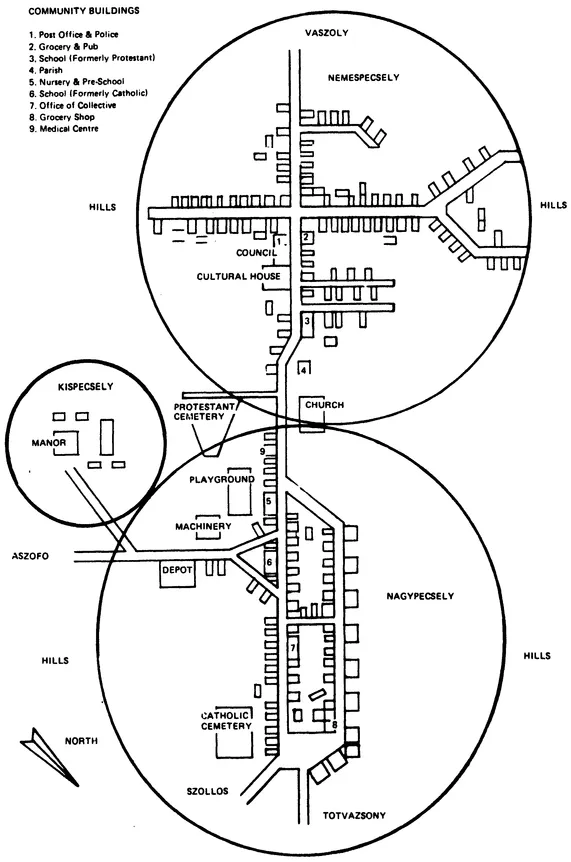

Pécsely is in the Transdanubian part of Hungary, inland from the shore of Lake Balaton (Maps 1.1 and1.2). It nestles in a small valley surrounded by gentle hills that open towards the lake like an amphitheatre. The flatland areas within the valley are adequately fertile for grain and pasture, while the hillsides are eminently suitable for vinegrowing. Several small streams criss-cross the valley, some marked by ruined water mills. The enclosing hills form a natural boundary separating the basin from the surrounding villages and marking a natural limit to the határ, that is, land belonging to the village.1 The geographic unity of the Pécsely valley (see Map 1.3) draws attention to the rigidity of the socially created boundaries that kept apart three tiny local communities in the basin until 1940.

Today, the village in the valley can only be pictured as two villages with some difficulty. The stylish white-washed Protestant Church stands in what appears to be the exact centre of the present village, closer inspection shows that the church marks the precise pre-1940 boundary; to the right lies Nemespécsely, to the left Nagypfécsely. A small stretch of land, no more than a couple of hundred yards wide, now used for vegetable gardening, separated the two sides. It is locally called a 'no man's land' (senki-földje) and only recently have a few houses been built there, materially expressing a slowly consolidating unity between the two sides.

Kispécsely, the third local unit within the valley, was not a village proper but a manorial estate (puszta) in-habited by a landlord and the labourers he employed. It is about 1 km away from the two villages, towards the lake. At present, the manorial house, outbuildings and labourers'

Map 1.1 Pécsely in Hungary

Map 1.2 The Balaton Region

Map 1.3 Pécsely (schematic)

quarters are used as the animal farming centre of the agricultural collective (Map 1.3).

The side of the village that was formerly Nagypécsely is made up of two parallel streets, lined with houses built mainly in the traditional peasant style of the region, facing sideways. The houses are fairly evenly spaced and are similar in style and size. There are also some recently built villa-style houses, and a new street is taking shape from the bare stretch of land which separates Nagy and Hemes. Two large modern buildings draw attention: the new administrative centre of the agricultural collective built in 1969 and the new nursery and school building completed in 1975.

On the opposite side Nemespécsely is much less orderly in its layout: its streets are tortuous, there are many small alleyways and unlikely entrances to houses, which vary in size, with the larger houses being interspersed with one or two room pre-war labourer quarters. The larger houses bear the 'NS' (noble insignia) with the name of the family who built the house. The council building, post office and Culture House are located in the centre of Nemes, as well as the house of the Protestant clergyman.

The layout of the two villages clearly shows how dissimilar they were: Nemes was a village of mainly noble, landowners' families, whereas Nagy was a village of serfs until 1848. Pécsely today ranks among the smaller villages in Hungary, with about 600 inhabitants in 197 households. It is characteristic of both the Nagy and Nemes side of the village, that a large array of stables, granaries, sheds and other agricultural outbuildings stands in ruins in the courtyards, material remnants of a lifestyle of traditional peasant cultivation that has nearly ceased to exist.

In the first month of fieldwork I was intrigued by the frequency with which local informants referred to their own and others' descent from serfs and nobles. Made redundant as far back as 1848, these terms sounded anachronistic in a socialist society. This is not to say that distinctions of serf and noble have retained much significance-they are no more than echoes from the past-but just as on the material level the villages' layout preserves the historical heritage, so these concepts reflect its vestiges in people's minds (cf. K. Szentgyörgyi, 1983).

There are records of the villages of the Pécsely valley dating back to the thirteenth century and it is likely that three hamlets existed before that time. From the fourteenth century they were the object of ownership disputes among various contenders. Among others, the Bishop of Veszprém, the Provost of Obuda, St Catherine's Monastery and the Abbey of Tihany claimed ownership of the serf holdings of the valley. By 1629 the Bishop of vesprém and the Provost of óbuda had successfully recovered their feudal rights from the rival contenders. From this period onwards the inhabitants of Nagy and Kis Pécsely were reported to be the serfs of the Bishopric of Veszprém and the Provostship, while Nemespécsely was inhabited mainly by nobles and a small minority of serfs, that is, it was a 'curialis' village.

In Hungary before 1848 the terms 'serf' and 'peasant' cannot be seen to be opposed to the terra noble (Nemes). Not all serfs were peasants-there were, for example, artisans and craftsmen among them-while the great majority of nemes were small landowners with peasant culture, lifestyle and means of subsistence.

The social divisions between the nemes and serfs was not as clear cut as the legal definitions suggest; wealth and landownership frequently cut across these divisions. Within the nemesség (nobility) only a small minority enjoyed the 'noble mode of life' (nemesi életforma) and were 'bene possessionati' (well-to-do gentry), who formed the social elite of the counties, held offices and upheld nemes pride and consciousness. The nemes of the curialis villages rarely shared the privileges of this lifestyle; they were mostly poor, their lands fragmented through inheritance. The majority of the nemes worked their farms themselves and their lifestyles were similar to those of the serfs. They were confined to their villages and their farms, weighed down by the drudgery of physical labour with almost the same level of culture, housing and dress as the serfs, in other words, they belonged to the same class as the serfs. Yet there were consistent differences in outlook and attitudes and the nemes families of Nemespécsely live in relatively better economic conditions than the serfs of Nagypécsely. Although peasants in lifestyle, the nemes were proud of their de jure superiority over the serfs of Nagypécsely and Kispécsely and these attitudes persisted until well after the abolition of serfdom in 1848.

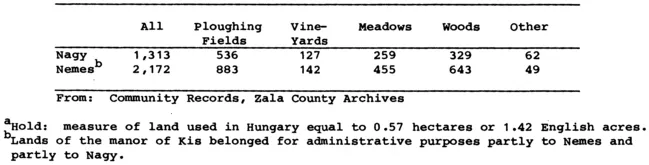

The twin villages of Nagy and Nemes and the manor of Kis had different landholding structures which rested on different principles of landownership and tenure. In 1842 the lands of the villages in the valley were constituted as shown in Table 1.1.

In Hungary the unit of serf holdings was the telek, the size of which was regulated countrywide.2 The serfs of Nagy and Nemes held mainly quarter serf holdings, that is quarter teleks and only one household held a full serf holding.

Table 1.1 Constitution of land of the pécsely valley in 1842 (in holdsa)

Table 1.2 Distribution of land among serfs by size (in holds)

In addition to the arable fields and meadows, most villagers had vineyards;3 only one third of the serfs had none. These vineyards were an important source of cash for the villagers-very probably the only source for the majority-and they compensated somewhat for the small size of their farmland.

About half of the serfs of Nagypécsely had enough land, draught animals and vineyards to make them self-sufficient at a subsistence level without the need to contract for labour regularly. However, their self-sufficient status might be considerably modified by the quality of their farmland as well as by the ratio of workers to dependants in the house-hold.

As the nemes residents of Nemespécsely were not taxable they were not listed in the records and information on their farmlands is lacking. In the 'Cadastre of Nobility of the Country of Zala' of 1790, however, the nemes of that village are listed. There were at that time 9 nemes families in Nemespécsely, comprising 29 households. They owned 1,213 holds of the local farming land, but there is no information about how it was distributed. If that land were equally distributed, each household would have had control of about 40 holds, that is 22.8 hectares, but in fact a much more unequal distribution is likely to have been the case. The land the nemes owned was about twice as large as the lands of the serf families, with correspondingly better economic conditions overall.

Neither the names nor the serfs had any chance of acquiring more land before 1848 because of the large allodial domain of the Catholic Church that took up part of the valley. All that could happen was redistribution of the land they held among their own numbers.

Although the declaration to emancipate the serfs in the spring of 1848 was the work of one day, the dismantling of the serf system went on for years, indeed almost three decades.4 On balance, while serfs won emancipation and full ownership of the farms they worked, they also lost a great deal of land which had hitherto been in their control. In addition they had to raise considerable sums of money to redeem part of the lost land.5 The new landowner peasants were, in fact, faced with many difficulties, for their farms had diminished and their debts increased. The new tax system6 was heavier than previously and had to be met in cash. This led to the impoverishment and ruin of a large number of farms; between 1870 and 1910 about 100,000 small farms were ruined.

After 1848 peasant production for the market increased, mainly because of the need to raise cash for taxes. Improvement of peasant production was facilitated by several innovations, such as the appearance of iron ploughs. Root crops and maize cultivation were more widely adopted by the late nineteenth century, resulting in better use of the soil. Improved strains of animals replaced the hardy, low milk and meat producing cattle and the good fat and meat producing mangalica pigs became common. Fodder crops, such as lucerne and sainfoin, were produced in greater volume so that the animals did not have to be pastured in the open all year round (Unger, 1973:224).

The dynamic growth of agriculture in the late nineteenth century was also associated with the development of capitalism and stimulated by the extensive market for Hungary's agricultural products within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The newly built railway network, as well as improved river and road transport, allowed for a more efficient distribution throughout the country as well as aiding export, although they did little for villages far from the major regional centres. Developments favoured the larger agricultural production units and rich peasants rather than the smaller peasants, who, lacking the necessary capital, were less able to switch over to better techniques. Unable to compete, large numbers of this class were impoverished and swelled the ranks of the agrarian proletariat seeking subsistence as itinerant workers on the railway lines and embankment building (kubikos). Others joined industry as unskilled workers or emigrated overseas.

This process was less marked in the Balaton region for a variety of regionally specific reasons. There was less emigration; indeed, on the contrary, there was a vast influx of immigrants from other parts of the country. Between 1870 and 1952, for example, the population of the north shore increased from 26,830 to more than 50,000 (Orbán, 1953:43). There was no industry in the area to attract new-comers until the 1920s when factories were established in Fëzfö and Vörösberény. The significant factors for the region's development were, in fact, tourism and viticulture.

From the 1880s onwards the lake shores became popular holiday resorts for the gentry, and the region was developed to cater for this demand. A boat service was inaugurated by the turn of the century and the Fured-Tihany-Keszthely railway line was completed by 1907. Almadi, beyond Fured, was the first resort to develop in this way and a large number of villas were built all along the north shores, offering good labour opportunities for the rural landless both from the region itself and to newcomers.

Quality wines were grown extensively and in 1870 there were 7,655 holds (about 4,363 hectares) of vineyards on the north shore in the hands of 5,575 owners (a mean of 1.33 holds per owner). Vine growing was not suited primarily for large-scale cultivation on large estates and was mainly in the hands of individual smallholders. These comprised not only peasants but also tradesmen, non-agriculturalists and the intelligentsia that lived in the region (Orbán, 1958: 44). However, between 1878 and 1880 phylloxera spread unchecked over the entire region and destroyed the greater part of the vineyards. Their re-establishment, using grafts to wild, disease-resistant stock, was started immediately afterwards, providing labour for many people. However, the previous extent of vineyards was never reached again, although by 1935 there were 5,127 holds (about 2,922 hectares) which were of superior quality to the strains they had replaced.

Throughout the late nineteenth century there was a constant flow of newcomers to the region who formed the bulk of the landless stratum. During World War I, development of the region slowed somewhat but picked up again in the 1920s and continued steadily in spite of the general economic recession of the 1930s. Building proceeded at a great pace and by the 1930s about 1,000 villas, many of them occupied throughout the year, had been erected around the north shore of the lake.

In view of these regionally specific circumstances, distribution of land among the peasantry was less unequal than elsewhere in the country (Orbán, 1958:45). The small and middle peasants could find markets for their wines and other products in the region itself, and were able to hold their ground better. The landless had more labour opportunities (for example, in construction) than elsewhere and were less dependent on seasonal labour on large estates and on individual peasant holdings. vineyards are very labour intensive, though mainly on a seasonal basis, and the reestablishment of vines in the area absorbed a great deal of labour.

The Pécsely valley is not located directly on the shores of Lake Balaton, but inland, in what may be described as the second ring of villages surrounding it. It is more isolated than the villages on the lake and no holiday villas were built in Pécsely in the 1930s. Generally, however, influences similar to those in the lakeside villages were at work.

In Pécsely the pattern of land distribution in particular and the lot of the villagers in general, were overwhelmingly influenced by decisions regarding the local manorial estates. In 1848, the Bishop of Veszprém and the Provost of Obuda granted tenure of their estates to two wealthy families, who remained in control of these lands and lived locally u...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- list of Tables, Maps, and Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART 1 ANTECEDENTS

- PART 2 AGRICULTURAL COLLECTIVIZATION

- PART 3 BEYOND THE COLLECTIVE

- PART 4 THE COLLECTIVE AND THE COMMUNITY

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index