eBook - ePub

The Hillary Effect: Perspectives on Clinton's Legacy

This is a test

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Hillary Effect: Perspectives on Clinton's Legacy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

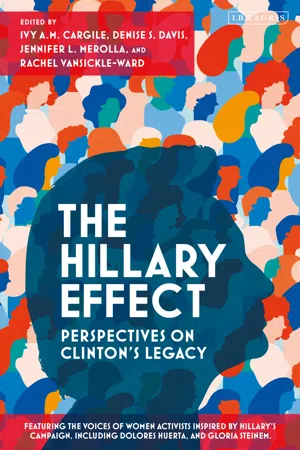

This volume of over thirty essays is organised around five primary dimensions of Hillary Clinton's influence: policy, activism, campaigns, women's ambition and impact on parents and their children. Combining personal narrative with scholarly expertise in political science, this volume looks at American politics through the career of Hillary Clinton in order to illuminate overarching trends related to elections, gender and public policy. Featuring an extraordinarily varied list of contributors working within the field of political science, and a fresh interdisciplinary approach, this book will appeal to broad range of politically engaged audiences, practitioners and scholars.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Hillary Effect: Perspectives on Clinton's Legacy by Ivy A.M. Cargile, Denise S. Davis, Jennifer L. Merolla, Rachel VanSickle-Ward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Corruption & Misconduct. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

“I’m With Her”: Clinton’s Impact on Women’s Lives and Ambitions

Preface

Jennifer L. Merolla

We are the ones we have been waiting for.

—June Jordan

From defying traditional roles of a First Lady, to declaring women’s rights are human rights, to being the first woman to win a major party nomination for president, Hillary Clinton has broken down barriers to gender equality both at home and abroad. Through her service and example, she has recognized the importance of putting oneself forward and taking risks. She has done this not because it was easy, far from it. Rather, she has done this because of her desire, passion, and determination to give women a voice and more equal footing in society. As she argued at the Vital Voices conference in Vienna in 1997:

There cannot be true democracy unless women’s voices are heard. There cannot be true democracy unless women are given the opportunity to take responsibility for their own lives. There cannot be true democracy unless all citizens are able to participate fully in the lives of their country.1

How did watching a high profile (arguably the highest profile woman political figure in the world), hyper qualified candidate, over the course of her career and campaign, shape women’s own ambition, priorities, and sense of self? The significance of role models is well documented in political science.2 According to theories of descriptive representation, seeing members of one’s group represented in political office can lead to a sense of political empowerment, and spur political engagement (Bobo and Gilliam 1990). A number of scholars have explored how the presence of women in elected office affects the political engagement of women. Some scholars have found that women come to have greater interest in politics, feel that leaders are more responsive to them and are more likely to participate when they are represented by a woman in office (Hansen 1997; High-Pippert and Comer 1998; Reingold and Harrell 2010). These effects even occur when women are present on the ballot (Hansen 1997; Wolbrecht and Campbell 2007).3 Most of these effects have only been explored at the congressional level, given the dearth of female candidates at the presidential level (prior to the 2020 presidential election). Furthermore, for all of this rich scholarship, existing research has not considered what the presence of women candidates, and reaction to that presence, has meant to women in their daily lives. The chapters in this section tackle these questions.

We argue that an important, and overlooked, effect of Hillary Clinton is how she has served as a role model to other women, even outside of the domain of politics. Her presence in politics, and reactions to that presence, even in the face of a devastating loss in the 2016 election, has led women to reflect on their own roles as they go about their daily lives and engage in the political world. The contributors in this section speak to the many ways in which Clinton and her experiences have transformed understandings of women’s presence across different institutional settings, and have helped inspire them to take action to bring about change. According to the contributors in this section, her journey, her spirit and resilience, her fights, including successes and failures, have opened eyes, ignited hope, provided strength, caused us to dig deeper, to want more, to fight for more, even after being knocked down.

Jennifer Piscopo, an associate professor of political science, speaks of her journey to study women’s representation in Latin America, which began at Clinton’s alma mater, Wellesley. Drawing from her expertise on representation, she discusses how two narratives in 2016—that women only supported Clinton because she is a woman, and that she is widely disliked—deny women their rights to representation. With respect to the first narrative, Piscopo argues that it neglects that these women see in Clinton their own “struggles, stories and ambitions.” The second narrative ignores the enthusiasm held among many of her supporters.

Contrary to the problematic narratives in media coverage, Piscopo notes that Clinton inspired women to want more, to demand more, to effect the change they believe is needed. So, they did not just turn out in 2016, but donated to the Clinton campaign, and after her defeat, they did not stay home, but harnessed their anger into action by marching, engaging and running for office in record numbers. And, as the other contributions in this section show, Clinton’s example also inspired them to want more and to demand more in their own lives.

Debra Van Sickle, a retired math teacher, takes us further back in time, and speaks of growing up in the “same America” as Clinton and becoming inspired during the presidential election of 1992, of the promise of getting “two for the price of one.” She was inspired by seeing a First Lady buck traditional gender roles, and angered by the backlash in the press. She speaks of her admiration for Clinton being linked to her complicated and nuanced life, relationships and accomplishments. The disjuncture between Clinton’s words and actions and how they are covered in the press has inspired her to “dig deeper to find the truth about events and people.”

Kathleen Feeley, a professor of History at the University of Redlands, brings us to Clinton’s next major milestone, running for a US Senate seat in New York, and how her run inspired women. Feeley recounts how Clinton was criticized for being a carpetbagger, since she was not from New York, but turned that “disadvantage” into an advantage, by going on a listening tour of the state: “The listening tour embodied the doggedness, earnestness, intellectual engagement, and feminist values—so often used to demean and dismiss Clinton—that have long inspired supporters.” She discusses the enthusiasm of women for Clinton during this election, even in parts of the state that were traditionally less Democratic. She also reflects on how Clinton’s resilience and example during that election inspired her to “stay the course and do the hard work” of finishing her dissertation, even in the presence of obstacles.

Jennifer Chudy, now an assistant professor of Political Science at Wellesley College, remembers her interactions with Hillary Clinton when she was an intern in her New York Senate office. She recounts how those interactions inspired her to be an attentive mentor. In a domain in which interns are often invisible, Chudy reflects on how being “seen” by Clinton was transformative, making her feel valued and heard. That experience was important in her own trajectory and in how she engages with her students. As a professor at Clinton’s alma mater, an all-women’s college, she also reflects on how Clinton has inspired her students, not only through her example as a public servant but also in her “strength and resilience.” She encourages their desire for more by seeing and supporting their potential, the way that Clinton did for her.

The last two contributions take us more deeply into the 2016 election and how women see in Clinton their own stories, struggles, and resilience. Rabbi Jaclyn Cohen reveals how Clinton’s “path-blazing presidential campaign and stunning defeat,” coupled with Cohen’s own entry into motherhood and all that goes with it, opened her eyes to how most of her life was spent “accommodating men.” While Clinton’s defeat was devastating to herself and her congregation, she notes that it may also serve as an important wake-up call for more of us to stand up in our personal and professional lives.

Brinda Sarathy, professor of Environmental Studies, poignantly reflects on her days in graduate school, of feeling like an imposter, feeling invisible, being mansplained to by “Theory Bros,” but surviving by being resilient and building supportive networks, and of going on to do the gendered service labor that is often performed by women faculty. These experiences are familiar to many women in male-dominated fields. Like many other contributors in this section, Clinton’s loss was painful, was personal and yet, motivating. Sarathy is now louder, more engaged, both in her career and in political life. She has embraced June Jordan’s empowering words “we are the ones we have been waiting for.”

References

Bobo, L. and F. D. Gilliam (1990), “Race, Sociopolitical Participation, and Black Empowerment,” American Political Science Review, 84 (2): 377–393.

Dolan, K. (2006), “Symbolic Mobilization? The Impact of Candidate Sex in American Elections,” Working papers. Institute of Government Studies, University of California at Berkeley, http://escholarship.org/uc/item/2qp5d81k.

Hansen, S. B. (1997), “Talking About Politics: Gender and Contextual Effects in Political Proselytizing,” Journal of Politics, 59: 73–103.

High-Pippert, A. and J. Comer (1998), “Female Empowerment: The Influence of Women Representing Women,” Women and Politics, 19: 53–66.

Lawless, J. (2004), “Politics of Presence? Congresswomen and Symbolic Representation,” Political Research Quarterly, 57: 81–99.

Reingold, B. and J. Harrell (2010), “The Impact of Descriptive Representation on Women’s Political Engagement: Does Party Matter?,” Political Research Quarterly, 63: 280–94.

Wolbrecht, C. and D. E. Campbell (2007), “Leading By Example: Female Members of Parliament as Political Role Models,” American Journal of Political Science, 51: 921–39.

1

The Stories Not Told

Misrepresenting the Women Who Loved Clinton

Jennifer M. Piscopo

I did not attend Wellesley College because of Hillary Clinton—at least not consciously. I didn’t want to go to a women’s college. In retrospect, my reluctance made no sense, because my teenage self was a feminist, even if lacking the academic vocabulary of feminism. I felt both rage and grief because my grandfather prevented my mother from going to college. A voracious reader of novels, I only read books by women authors that featured women heroines.

It was 1998. Clinton’s comment about staying at home and baking cookies was years past, but frequently resurrected in the media. I remember thinking, “Of course she wouldn’t want to stay home, that sounds boring.” Whatever the story of my life would be, like Clinton and the heroines of my novels, I wanted more.

In the end, I chose Wellesley. A prospective student visit showed me what happened when smart women came together without limitations. The banners said, “Women who will make a difference in the world.” Wellesley groomed us for excellence. No subjects, careers, or ambitions were off limits. At some earlier point, I had received the message that math and science wasn’t for girls. At Wellesley, a woman Astronomy professor said to me, “But you are really good at solving these problems.” My self-understanding turned upside down. Each day was a lesson in how gender stereotypes shape the limits of the possible, and how role models undo these norms.

I minored in Astronomy, but united my interests in global affairs, political science, and women’s studies by majoring in Latin American Studies. Women played significant roles in the civil wars, social movements and democratization processes that shaped Latin American politics in the 1980s and 1990s (Jaquette 1994). Since I was born after the heyday of second wave feminism in the United States—and the US women’s movement remained absent from my high school history books—Latin America drew my attention for the sheer numbers of women in public roles. At the same time, I was thrilled to share a Wellesley connection with Hillary Clinton and Madeleine Albright, women who broke barriers closer to home.

My career became dedicated to understanding women’s political representation: how and when women attain political power, and why it matters. When political scientists talk about political representation, they mean more than just choosing legislators from a certain district. Representation also means feeling seen and feeling included. People in office need to resemble the people they represent, in terms of their identity and their lived experiences (Phillips 1998). I focused on Latin America, where some countries elect legislatures comprised of over 40 percent women.1 I obtained my PhD in political science, joined the faculty at an elite liberal arts college, published my research and began consulting for organizations like UN Women.

So by 2016, I had the feminist vocabulary to understand exactly what made media coverage of Clinton’s campaign elicit that familiar mix of rage and grief. Two media narratives in particular left me seething: that women supported Hillary just because they wanted a woman president, and that voters did not like her.

These narratives deny women their rights to political representation. Clinton’s career encapsulated the struggles, stories, and ambitions of so many women. She...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- About the Contributors

- Prologue: The Path up Is Always a Jagged Line

- Introduction

- Part One “I’m With Her”: Clinton’s Impact on Women’s Lives and Ambitions

- Part Two “Agents of Change, Drivers of Progress” Clinton’s Role in Shaping Activism

- Part Three “When There Are No Ceilings, the Sky’s the Limit”: Clinton’s Impact on Campaigns and Elections

- Part Four “Our Children Are Watching”: Clinton’s Impact on Parents and Kids

- Part Five “Deal Me in”: Clinton’s Impact on Policy

- Notes

- Index