![]()

1

First things first …

Summary

This book overall is an attempt at persuading fellow artists that it is in our interest that we consider what we do in disciplinary terms, that we regard art as a discipline akin to any other knowledge-forming discipline. This argument lies in sharp distinction with how we have been thinking about art for the past 150 years. For 150 years, since Romanticism, art has been understood and valued as a form of self-expression and most definitely not as knowledge producing. Simultaneously, and particularly throughout the Modernist period of the twentieth century, art was imagined at the vanguard of society, leading society into a better world from an imaginary front. At the turn of the twenty-first century, this seems to have changed.

Instead of performing artistic and social ideals, artists have adopted neoliberal norms as our own, while also complaining of the ills of neoliberal capitalism, despairing of the accelerated and unmitigated form of global neoliberal capitalism that produces precarious labour conditions and extremely unequal distributions in wealth and opportunities. We complain yet, simultaneously we betray many of the values underpinning neoliberalism, including being popular, accepting metrics for analysing our value(s), and the idea that the market is the rightful arbiter of taste. Even the very definition of art has now been left to the market.

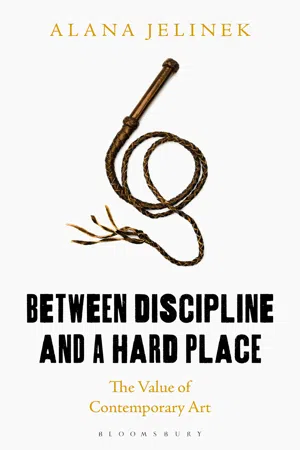

Between Discipline and a Hard Place is written to counter these neoliberal norms, as a proposal for the idea of discipline as a strategy for disrupting neoliberalism from within.

Embracing disciplinarity is not to ignore the critique put forward by Michel Foucault and others. Instead, this book is a proposal to build on critiques of Discipline in the Modern era, and create a form of self-conscious and performed discipline as a strategic way of navigating a world characterized by the almost ubiquitous internalization of neoliberal values. However, this proposal is more than strategic. The idea that art is knowledge-producing is also true. Art practice operates just as any other disciplinary knowledge system does and it behoves artists – all of us, inclusively – to acknowledge this. What gets in the way of artists owning the fact that we create knowledge is that historically, since Modernity, the definition of knowledge has been limited to a narrow one, confined to scientific norms. The narrowing of knowledge is a product of the Modern discipline. With Postmodernism we have learnt to see that, in reality, knowledge is achieved in many modalities. Art is one of these many modalities. It turns out that art is nothing like that described by the majority of art historians or philosophers.

First things first …

I have written Between Discipline and a Hard Place in order to consolidate arguments made in my previous monograph This Is Not Art (2013) to build on them and to respond to the interesting and relevant criticisms of that book. At that time I proposed the idea of disciplinarity strategically. Since then, I have realized that understanding art as a knowledge-forming discipline is more than strategic. It is also true. Thinking about art in disciplinary terms goes beyond simply strategizing ways of navigating an art world characterized by its internalization of neoliberal* values. The various interconnecting essays here describe in greater detail how art is a knowledge-forming discipline akin to any other knowledge-forming discipline and they describe the type of knowledge that art can be said to produce. Between Discipline and a Hard Place ends with a proposal for a completely different paradigm from the progressivist one that dogs the history of art despite decades-long critique of the notion of progress.

Discussion about the value of the type of knowledge that universities produce has informed my thinking on the question of art as a knowledge-forming discipline.1 It is apparent to me that if art departments in universities understand our position as similar to the rest of the knowledge-forming disciplines found in universities, similar to the rest of the arts, humanities, social sciences and sciences, we would be better placed to make strategic alliances, lobbying in common terms and expressing our common value to a wider public and to government. Instead, artists and artists who teach in universities refuse commonality. We imagine ourselves as exceptional: we come from the anti-discipline, radical tradition of the Art School, not the conformist university or the practical polytechnic. We refuse the concept of expertise. We are not experts in our field, but something else. The history of Art Schools, pre-existing university art departments, leads us to believe an art education is distinct from a university one. But we no longer have the luxury of positioning ourselves as unlearning, anti-discipline, anti-expert, as if expertise lies elsewhere. It is highly disingenuous given that art is taught in universities and that art practice is a valid methodology for research funded by Research Councils and a valid outcome of research when assessing research excellence in the UK’s Research Excellence Framework.

More importantly, the anti-discipline position does a disservice to what we do as artists. Ultimately, it undermines our value. Artists have a knowledge base and an expertise, which is thrown into relief particularly in inter- and multi-disciplinary collaborations and whenever we work outside the art institutions, in ‘the community’. Teaching undergraduates, and also graduates who come from a non-art discipline, be it design, psychology or chemistry, it is apparent that a great deal of time and energy is required to help the student ‘think like an artist’, to move beyond the design paradigm of outcomes and servicing a client’s vision, the utilitarian, positivist experiments of the sciences or the illustrative impetus of most high school art. Perhaps an overblown phrase ‘thinking like an artist’ is meaningful, and it goes beyond Bourdieu’s ‘habitus’* or the embodied, tacit knowledge described by anthropologists such as Tim Ingold and Trevor Marchand. It is at the heart of the discipline of art.

Art within neoliberalism

To briefly recap arguments made in This Is Not Art about neoliberalism and the art world’s internalization of neoliberal values, artists today, having moved from the Modernist paradigm, operate without a sense of endogenous**, or discipline-specific values. The vacuum artists have created by refusing to define art or to address the question of who is an artist is filled by default. And the default in a neoliberal paradigm is that value is (and must be) established by the market. Market mechanisms ascertain the value of art in addition to any other public goods. Publicly funded organizations that provide public goods are required to justify their funding in terms of market-based econometrics where they cannot be valued in direct market terms. Prior to a generalized internalization of neoliberal values, which in the UK occurred around the turn of the millennium, the value of art was described in Romantic and avant-gardist terms of advancements in the aesthetic and the socio-political. Artists then (most often in the form of white bourgeois men) were geniuses of highly refined sensibilities moving society towards ever-greater moral and/or aesthetic heights. Anecdotes were traded within artistic circles about bourgeois audiences and aristocratic patrons. Artists regarded themselves as leading wider society, albeit more often than not only the haut-monde, into difficult and challenging territory, into new and better worlds. We had a clear role, operating at the vanguard, both aesthetically and socially. As the archetypal Romantic genius, for example, biographers of Ludwig Beethoven describe Beethoven’s sneering tolerance of his aristocratic patrons, who were keen to be associated with the new forms of artistic language, to have proximity to genius. Today this attitude seems quaint or worse: artists of the past are accused of undemocratic attitudes, as well as of hypocrisy.

Rather than maintaining hierarchies and exclusions, today, we don’t even attempt to define what our values are. Because we have no definition for art, and art can be done by anyone, it has become impossible to argue what actually art is, what art does in society and what artists, as artists, do or contribute to society. Yet we also maintain that art is of great value and not just to investors.

The idea that anyone can be, or is, an artist has been around since Romanticism in the mid-nineteenth century. It is a generally accepted art world homily with currency in wider society. Undifferentiated inclusion is imaged to be democratic. But this idea must be contextualized. The Romantic notion of inclusivity was born of a time when the vast majority of the population had at best a basic education plus highly constrained choices, as compared with the privilege of the middle and upper classes, from whose ranks artists almost invariably came. The majority of the population had no right to vote or stand for election. The assertion that anyone could be, and is, an artist was a challenge to class hierarchies and the inequalities of the time, part of a societal push towards a democracy of, and for, all.

Today, the majority of people in the UK and other ‘economically developed’ democratic nations are middle class (however contested this category) and have access to some amount of time and resources for art, if they choose to engage with it as a practice or as a leisure pursuit. But this reality of democratic inclusivity masks its opposite. The overwhelming majority of both public and private resources for art go towards a vanishingly tiny percentage of practising artists. Moreover, it is artists with existing class, race and gender privilege who are in receipt of the most public and private resources generally, albeit there are notable and high-profile exceptions.2 My argument is that we cannot afford to hold onto the agreeable Romantic ideal of total inclusivity in the face of realities that serve an increasingly hierarchical status quo. We need to rethink a class of artist that happily upholds the values of a neoliberal status quo by imagining we operate in a meritocratic system – that we deserve our luck.

The most visible art attracting the largest amount of art world discourse occurs in a system bank-rolled by transnational corporations with reputations to refresh and plutocrats trading money for cultural capital,3 legitimized through the museums and Kunsthallen of democratic nations. Spectacular contemporary art (spectacular* also in the sense critiqued by Situationist, Guy Debord) is funded through the sponsorship of corporations and super-wealthy individuals. In the past, when artists modelled ourselves on avant-gardist notions, from the mid-twentieth century until the early 1990s, we ignored Venice and the tastes of biennale funders, its audiences and curators. Instead, artists working at ‘the cutting edge’ attended open studios, artist-run spaces and artist initiatives as the sites of artistic innovation. While artist initiatives also exist today, it is to a much smaller extent and in the cities dominated by global capital such as London and New York, shoe-string budget artist-run initiatives have mostly receded into historical memory for reasons of gentrification and a lack of stable public funding (see This Is Not Art).

Contemporary artist and theorist Gregory Sholette describes the neoliberal art world as one maintained by a ‘dark matter’ of ignored and overlooked artists, 97 per cent of all practising artists.5 In reality, it is far less than 3 per cent who are both visible and resourced. It is closer to the graph of unequal distribution of wealth in developed economies, that is, 0.001 per cent. Sholette makes an important point that most artists do not get paid or are underpaid for their ‘artistic labour’; yet, we financially maintain the corporate, well-endowed art world through paying entrance fees to galleries and museums and volunteering. However, the use of the dark matter metaphor demonstrates that even the most political, and Marxist, of artists have internalized neoliberal values. By using it, Sholette substantiates the values of the neoliberal art world. The metaphor naturalizes the idea of 3 per cent. In reality, the ‘3%’ isn’t natural. It is 0.001 per cent and it is sustained by a closed market of courtly biennials and Kunsthallen that largely reflect the specific (and often conservative and cliché) tastes of the corporate rich.6 We don’t need to legitimize the corporate art world by attending, or attending to it. We have choices. This is not to say that uninteresting, conservative, cliché, populist art occurs only in the mainstream and well-funded venues. This is simply not the case, and to portray it thus would be to resurrect a cliché from the archives of Modernism: that bourgeois taste is conservative and the true artist, namely the avant-garde artist, works outside and beyond this. Instead, the point is that interesting, compelling and important art also occurs outside the narrow circles of the corporate rich. If 99.999 per cent of artists work beyond the venues and budgets of the 0.001 per cent, we should have plenty of interesting and compelling artists to engage with.

Historically, wealthy collectors working with well-networked dealers have been central to the promotion of artists, as New York Modernist art dealer Leo Castelli (1907–99) amply demonstrates. But one difference between the mid-twentieth-century art world and today is the structure of the art world itself. An argument I make in This Is Not Art is that today there is a full integration of all aspects of the art world. In the past, there were different and competing mechanisms of support for artists and for art, not only in the UK but in the United States and beyond. There were distinct private and public spheres, as well as the possibility of self-organization, before the private property boom in real estate and the marketization of intellectual property (IP) in the late 1990s. Before this, the UK boasted at least two different systems of support for contemporary art and artists which, while not mutually exclusive, were distinctive. One was the commercial gallery system and the other was publicly funded by the Arts Council of Great Britain operating at an arm’s length from UK government. Today and consequent of New Labour policies for the arts during the year 2000, which removed the arm’s length aspect of arts funding, there is a full integration of the public and the private systems of support for the arts. Added to this, a lack of affordable housing and the dismantling of squatter’s rights have led to the destruction of artistic self-organization unless artists personally have a great deal of capital behind them. And some artists do have a great deal of capital behind them.

This consolidated system of support has created a certain homogenization of contemporary art practice. Art can be anything, but it isn’t. Instead (as I argue in more detail in a chapter in this book, ‘Corporate Censorship’), there is an endless variation on a few themes. This idea builds on the work of sociologist of economics, Michel Callon, and economist, Jean Gadrey, who separately detail the mechanisms of market convergence and the effect this has on innovation and diversity. In short, when markets get involved, true diversity is inexorably and inevitably driven out. This process of homogenization is true across technology, scienc...