1

The Background to the Story

At Meydani, the ‘Square of the Horses’, the great rectangle of turf that lies in the south-east corner of modern Istanbul, still marks the heart of the city. One end of it reaches south toward the Sea of Marmora, and the other stretches northwards towards Hagia Sophia, Constantinople’s cathedral built by the emperor Justinian, and now his most conspicuous monument. The Turks who captured Constantinople in 1453 transformed it into a mosque, and in the twentieth century, it became a museum. At Meydani is all that remains of the great Hippodrome of the ‘Royal City’, that once accommodated up to 100,000 spectators. Its seats have vanished long ago, and the racecourse itself lies buried under three metres of earth, heaped over it by the passage of time. Yet if we stand in its midst, and employ only a small morsel of imagination, the years drop away and we can conjure up the scenes that once took place here: teams of sweating horses bursting out of the starting gates, whipped to a hard gallop by their drivers as they teetered on their flimsy chariots, racing down one lane of the course, wheeling around the turning post and then racing up the other lane, while the spectators cheered, and the sovereign of the Roman Empire, God’s deputy on earth,1 surveyed the scene from his seat high above in the kathisma – the imperial loge, connected to the palace by a private passageway. Twenty-five races filled up a day of fun.

Little remains now of Constantinople’s great Hippodrome. Four gilded bronze horses from above the starting-gates, once belonging to a four-horse chariot, now adorn the cathedral of San Marco in Venice, where they were taken after the Fourth Crusade in 1204 plundered the city. The spina – the low wall which divided the racecourse into two lanes, once bristled with monuments appropriated from assorted sites in the empire. Constantine, the founder of Constantinople, set the example: before he died, the spina bore no fewer than 20 filched monuments, and Constantine’s successors followed his example up until the time of Justinian. Two are still to be seen. One is a bronze column of three serpents intertwined, which was filched from the sanctuary of Apollo’s oracle at Delphi.2 It commemorated a moment of glory in the history of classical Greece, when the Greeks defeated a Persian invasion at Plataea in 479 BCE. In modern Istanbul, the column sits in a shallow well, for the ground level has risen and the column base is now far below the surface of the earth. The other is an obelisk which the Pharaoh Thutmose III erected three and a half millennia ago in Egypt. The emperor Theodosius I, brought it to Constantinople and erected it on a new base to mark the centre of the Hippodrome. On the four sides of the base are sculptured reliefs, one of which shows Theodosius himself and his courtiers watching the races from the kathisma. Fast forward a century and a half from Theodosius’ reign, and we can imagine the great emperor Justinian himself sitting in immobile splendour in the same kathisma, which he remodelled early in his reign to make loftier and more impressive.3 His partner-in-power, Theodora, an ex-actress who played her most famous role as empress of Romania, would not be at his side, for women did not attend the races; in fact, a wife who went to the races gave her husband a lawful cause for divorce.4 Yet Theodora knew the Hippodrome well. As a child she had come there as a suppliant, along with her two sisters, to beg for the compassion of the fans.

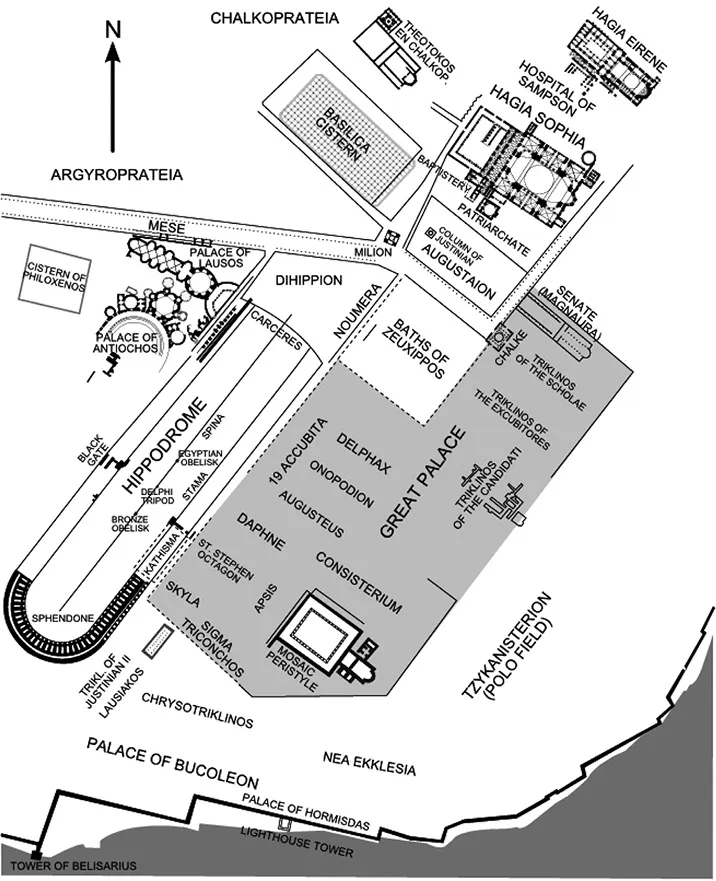

Great Palace, Constantinople.

These monuments are poor remnants of a splendid past. Only a few of the buildings that were once Justinian’s pride survive in Istanbul of today. The mosque of Sultan Ahmet, the so-called ‘Blue Mosque’, stands where the imperial palace once sprawled over the south-east corner of the city. Archaeologists have recently begun to unearth some of its remains, including remarkable floor mosaics which hint at what its grandeur must have been. Justinian’s Hagia Sophia has endured the vicissitudes of time, though it no longer confronts the imperial palace across the Augustaeum square, so named after Constantine’s mother, Helena Augusta, whose image once stood on a column there. This was the heart of Rome’s successor city, Constantinople, capital of eastern Romania that survived the decline of the western empire. Here in the Hippodrome the great emperor, heir to a line of emperors that began with Imperator Caesar Augustus, came face to face with his subjects.

There was a rough-and-ready democracy in the Hippodrome. The crowd gathered there to acclaim new emperors, for the concept that the emperor was a magistrate elected by the Roman people was not yet dead. Many centuries had passed since the assemblies of the ancient Roman republic passed laws and elected magistrates; yet the populace of New Rome still exercised its ancient right to make its will known to the emperor as he sat in his imperial loge. There might be direct dialogues between the people gathered in the Hippodrome and the emperor, who communicated with them using a herald trained to project his voice. Nor did the mob hesitate to howl protests and maledictions up at the emperor if his policies displeased it. Between 491 and 565 we know of at least 30 riots there.5 One erupted in 507, when the emperor Anastasius refused to free some prisoners whom the people favoured, and they hurled rocks at him as he sat in his imperial loge. Once again, in 512, a wrathful mob in the Hippodrome almost toppled the same Anastasius from his throne. Twenty years later, the emperor Justinian saved his regime by butchering rioters that packed the Hippodrome to acclaim a replacement emperor. It must have been in this same Hippodrome, one day in the reign of Anastasius, that the little girl who would later become the Augusta Theodora made her first appearance before people of Constantinople.

Chariot racing and, for that matter, most public spectacles in the cities of the empire, were managed by production companies, or ‘factions’, that took their names from the ribbons worn by their horses. There were the Reds, Whites, Blues and Greens, and each colour had its own party or group of fans which sat together in separate sections of the Hippodrome. The tradition went back to the great Circus Maximus of Rome on the Tiber – the ‘elder Rome’ – but in the fifth century, the factions had developed into production companies in the entertainment industry, responsible for the performances in the hippodromes and theatres of the empire. The Blue and the Green factions were the dominant ones and the Reds and Whites were paired with them, White and Blue teams racing together against Greens and Reds. Each faction’s aficionados cheered on their teams and howled curses at their rivals. The Blues and the Greens in particular had companies of loyal supporters who were as passionate as the fans of modern football teams.6

Every race was moment of wild exhilaration. The trumpet sounded, the starting gates opened, and the horses plunged forward, hoofs pounding. A roar of applause mingled with jeers and taunts for the losers thundered from the seats. Here was where the young males of Constantinople sublimated their testosterone rush, for they had few other outlets: the gymnasiums and the ephebate culture that was once an important part of the classical city had not survived the fifth century.7 In his imperial box the emperor surveyed the scene with regal dignity. Emperors were above crass displays of emotion. Yet it was the imperial stables that provided some of the race horses – perhaps by Justinian’s reign, all of them – and the emperors were expected to be aficionados of one team or another. The emperor Zeno (474–91) sided with the Greens; his successor, the Anastasius (491–518) who was no great supporter of public spectacles, was nonetheless a fan of the Reds, and Justinian and his empress Theodora were both fervent partisans of the Blues – especially Theodora, and the reason for her partiality went back to her childhood.

Sometime in the opening years of the sixth century, while Anastasius was emperor, Acacius, the bear-keeper of the Green faction died. The factions maintained a supply of wild beasts, some of which were destined for the wild beast hunts (venationes), which were a favourite Roman spectacle, pitting wild animals and huntsmen against each other in the arena. The beasts were slaughtered to the delight of the spectators as they watched toreadors perform tricks such as vaulting over the back of a frantic animal as it charged, and sometimes they had the additional amusement of seeing one of them disembowelled. Unlike the fake ferocity and the improbable stunts of professional wrestlers on television, the acrobatics of the toreadors endangered life and limb, and the blood in the arena was real. Anastasius outlawed these extravaganzas of butchery in 498, but they soon made a comeback, probably even before Anastasius died.8 When Justinian inaugurated his consulship in 521, he presented games that featured the slaughter of 20 lions and 30 panthers in wild animal hunts. He was doing nothing unusual, for consuls regularly presented costly inaugural games that included wild beast hunts, and Justinian promulgated a law ordering the consuls to make proper arrangements for them.9 Some of the money lavished on the games trickled down to the poor, among them entertainers from the theatre. Tastes change, however; the year 537 saw the last venatio in Constantinople. The consulship itself was abolished in 541 and the name of the consul of the year no longer appeared on Roman laws. Costs had to be cut; the empire was gearing up for renewed war with Persia and consular inaugurations, which cost 2,000 gold pounds, most of it supplied by the imperial treasury, were a waste of money.10 At any rate, if someone lusted after the title of consul, honorary consulships were still for sale.

Yet bears were also performers: dancing, or taking part in acrobatic acts. Our only source for the story of Acacius describes him as the ‘keeper of the wild beasts used in the hunt’ with the title ‘Caretaker’, or ‘Master of the Bears’.11 Since Anastasius’ ban on the hunts was probably still in force when Theodora was a young girl, Acacius probably trained the bears that performed in the Hippodrome for the crowd in the entr’actes between chariot races. A mob left without entertainment could become a dangerous thing, and while the Hippodrome attendants were removing splintered chariots and injured horses and bringing the teams for the next race into the starting gates, the factions that managed the races provided distractions – acrobatic acts, mimes, dances and performing bears. The speech-writer, Choricius from the school at Gaza,12 a contemporary of Theodora’s youth, who wrote a defence of mimes, remarked that chariot races fired the passions and spectators with their passions aroused could be dangerous to public order; but mimes gave pleasure without passion. It was an example of judicious crowd control and Acacius’ job was to provide bears that could perform tricks or, should the entertainment industry require it, be slaughtered for the amusement of the spectators.

In Constantinople’s class structure a bear-keeper’s rank was at the bottom of the ladder and history would never have noticed Acacius’ death, except that he was the father of the future empress Theodora. He left behind him his widow and three small daughters. Comito, the eldest, was not yet seven years old, and Theodora hardly more than five. The youngest, Anastasia, must have been only a toddler and, since she fades out of the story, she may have died young. Sons generally followed their father’s trade, and if Acacius had had an adult son, probably he would have taken over the job that his father left vacant. But he had no son. However his widow, who belonged to the Constantinople theatre crowd, was not without resource. She quickly found another husband, thus acquiring a man to assume Acacius’ post and support her little family into the bargain. Or so she hoped. But her scheme failed.

The job of bear-keeper must have been a coveted one, for in a pre-industrial city like Constantinople, demand for steady employment fell far short of supply. Constantinople’s main economic activity was the business of governing and there was no industrial base to absorb surplus labour. Tradesmen belonged to guilds where a son followed his father’s occupation, and outsiders could not break in without an entrée. A post in the imperial bureaucracy was a road to wealth for men with the proper education, but for the untrained worker there was only occasional employment. Life for the unskilled masses – at least if they were young and male with only strong muscles to offer for hire – consisted of temporary jobs, punctuated by street fighting, church services and the chariot races in the Hippodrome. A bear-keeper had steady employment; perhaps he even had a slave or two at his command, which allowed him a morsel of self-importance. More than one man coveted the vacancy created by Acacius’ death.

It was the lead pantomime dancer of the Green faction who had the right to make the choice. Factions were business organisations and the lead dancers also served as administrative officers who oversaw staffing and discipline. It appears that their responsibilities even extended to crowd control in the Hippodrome, for three times in Anastasius’ reign, when the demes13 were unruly, the emperor exiled the lead dancers of both factions.14 Byzantine bureaucrats, as a matter of course, supplemented their salaries with bribes, and the lead dancer of the Greens was no better or worse than any other official with a crumb of power. Bribery greased the wheels of Byzantine officialdom. Asterios, the lead dancer of the Green faction, took a substantial inducement from another candidate and rejected the new husband of Acacius’ widow.

The rejection had one unintended consequence: it ensured that history would remember Asterios’ name; but, at the time, his decision spelled utter disaster for this little family. Theodora and her two sisters were left with a stepfather, but no income. They were destitute. Their mother played her final card. When the next show took place in the Hippodrome, she dressed her little daughters as suppliants, with wreaths on their heads and garlands in their hands, and had them sit in the dust in front of the section reserved for the Green fans. They begged for compassion. But the Greens had none to give. No one cared to challenge Asterios’ right to select the new Master of the Bears. The Green fans would not interfere. Stars of the theatre and the hippodrome had claques15 to lead the applause for their performances, and mock their rivals, and Asterios’ claque may have led the jeers for this first public performance of Theodora and her sisters. Theodora did not forget the rejection.

But the Blues were more sympathetic. As luck would have it they had a vacancy, for their Master of the Bears had just died and their faction needed a bear-keeper. They took pity on Theodora’s little family, and gave her stepfather the job. We hear no more about Theodora’s stepfather, nor about her mother either except that she put her daughters on the stage as soon as they were old enough. But t...