![]()

PART I

WHAT IS THE ISSUE?

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

In this opening chapter, we introduce user engagement as integral to current efforts aimed at improving the generation, mediation and utilization of research-based knowledge across the social sciences and public policy. We outline our perspective on user engagement in terms of an interplay of the different kinds of knowledge and expertise held by researchers and users. We then consider its connection with debates and developments concerning: research quality and relevance, modes of knowledge production, and research use and impact. We argue that user engagement needs to be understood as a complex and problematic concept that can present challenges and tensions for researchers and research users alike. This is illustrated through four key areas of potential difficulty: conceptualization, manageability, superficiality and limitations in scale, and evidence base. The chapter ends with an overview of the structure of the rest of the book.

Background

User engagement has become part of the landscape of contemporary social science research. Against the backdrop of evidence-based policy and practice agendas as well as critical questioning of much social science research, calls for increased involvement of research users in and with research have proliferated. References to user engagement are now seen in research funding requirements, national research strategies, international policy developments and a growing number of practical initiatives. All applications to the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), for example, must specify plans for ‘Communication and User Engagement’, and ‘being of value to potential users’ is held up as one of the five characteristics of all successful ESRC research applications (ESRC 2009b: 9). Similarly, charitable funders such as the Nuffield Foundation make it clear that applicants should ‘have identified those to whom the outcomes of the project will be most relevant, and have engaged them where possible from the early stages’ (Nuffield Foundation 2010: 2).

More and more large-scale strategic research developments have at their centre notions of partnership, collaboration and engagement. The UK Teaching and Learning Research Programme (TLRP) explicitly emphasized ‘user engagement throughout the research process’, both in terms of practitioner involvement in projects and liaison with national user and policy organizations (Pollard 2004: 17). Similarly, the Scottish Applied Educational Research Scheme (AERS) was based on the core principle that ‘the best way to enhance the infrastructure of educational research is through collaboration and a spirit of inclusiveness’ (Munn et al. 2003: 4). Alongside these developments, there are also increasing numbers of research projects, programmes and centres seeking strong user representation on advisory panels and steering groups, and growing interest in collaborative and participative approaches within primary research and research synthesis. In this way, user engagement has become integral to efforts aimed at reforming and improving knowledge generation, mediation and utilization across many areas of public policy.

Despite these developments, it is our contention that user engagement remains poorly understood both as a concept and as a process. In this book, we look at users in terms of practitioners (those involved in guiding learning, shaping learning environments and supporting learners’ well-being), service users (children, young people, adults, families and/or identified groups receiving specialized services), and policy-makers (local, regional and national politicians, civil servants and administrators, political advisors, research funders and government agencies staff ). Some users in each of these groups will have specific research skills such as basic inquiry skills that they learned during school and/or in further and higher education. Some may have significant expertise and experience on which to draw when either using or engaging in research. We look at the engagement of users both in terms of being involved in research processes (engagement in research) and engagement with research outputs (engagement with research). Most importantly, we see user engagement in terms of an interplay between the different kinds of knowledge and expertise held by researchers and different users. Hence, we explore user engagement in terms of knowledge exchange processes that involve different players, are multi-directional and have strong personal and affective dimensions.

Taking this view, we see the task of involving users in and with research as a demanding undertaking that asks new questions of research and necessitates new skills from researchers and research users alike. Furthermore, as shown by reviews of strategic initiatives such as TLRP, we are aware that user engagement can raise difficult political and ethical questions:

The risk of tokenistic forms of engagement, the competing pressures on users’ time and capacity to engage, the particular kinds of skills and understandings that this kind of work requires of researchers, as well as deeper-seated issues relating to the politics of user engagement, user roles and research ownership, were manifest to different degrees across the Programme.

(Rickinson et al. 2005: 21)

In view of these complexities, this book draws together recent theoretical debates, practical developments and empirical evidence on how research might be developed through user engagement. It seeks to provide:

- conceptual guidance on different approaches and interpretations of user engagement;

- examples and evidence of effective strategies for engaging practitioners, service users and policy-makers;

- capacity-building ideas and implications for researchers and research users.

The arguments and examples presented in this book grew out of a TLRP-funded thematic seminar series which, in 2005 and 2006, explored the implications of different forms of user engagement for the design of educational research (see Appendix). Seminar participants included researchers from TLRP projects, senior civil servants, representatives of research funding organizations, education practitioners, research mediators, government analysts and policy advisors, and researchers from fields beyond education such as social work and health.

One of the most important things that became clear during the seminar series was the dynamic nature of the terrain and debates surrounding user engagement. It was clear that initiatives such as TLRP and AERS have afforded researchers the opportunity to try out various strategies and approaches to working with users. Practical knowledge and reflective understanding on this issue is therefore developing. At the same time, the landscape of knowledge generation, mediation and utilization right across public policy has been fast changing as new players, practices and processes have taken shape. It is therefore crucial that our discussions of user engagement are set within the context of wider developments in social research, policy and practice. It is also critical that user engagement is approached as a complex and problematic concept in its own right with inherent challenges and tensions. It is to these two issues of wider contexts and challenges, and tensions, that we now turn in the following two sections.

Contexts and Dimensions of User Engagement

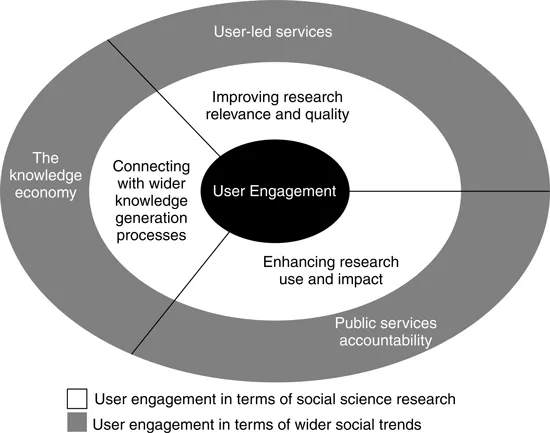

While interest in researcher–user collaboration and knowledge utilization is by no means new (e.g. Weiss 1979; Huberman 1987, 1990), contemporary support for user engagement needs to be understood within the context of recent developments in social science research and public policy generally. As shown in Figure 1.1, user engagement has close connections with strategies and debates concerning research quality and relevance, knowledge generation, and research use and impact. These concerns, in turn, can be linked with wider social trends relating to user-led services, the knowledge economy and public services accountability.

Improving Research Relevance and Quality

A common argument within critiques of social science research has been that it has been too ‘supplier-driven’ and so insufficiently focused on issues of importance to users (in education, for example, see Hillage et al. 1998; Prost 2001). Alongside relevance, there have also been concerns about quality. Reviews of educational research in England, for instance, argued that where research did address policy and practice questions, it tended to be small scale, insufficiently based on existing knowledge and presented in a way that was largely inaccessible to non-academic audiences (Hillage et al. 1998).

Figure 1.1 User engagement developments in research and wider society

Greater involvement of, and collaboration with, research users has been seen as an important way to redress such shortcomings (Rudduck and McIntyre 1998). This thinking can be seen very clearly in the policies and publications of major funders. The ESRC, for example, emphasizes that ‘on-going relationships between researchers and research users are the key to ensuring that research is relevant and timely’ (ESRC 2009a: 15). Along similar lines, leaders within the educational research community have argued that:

[t]o be convincing, to claim authority, we have to demonstrate both the relevance and the quality of our work. [. . .] This is the rationale for the authentic engagement of research users at every stage of the research process, from the conceptualization of key research issues onwards.

(Pollard 2004: 17)

The contribution of users to research agendas is an important part of the potential link between user engagement and research relevance. With this, however, there is the very important question of scale and the need for partnerships with research users to be strategic as well as project-based. As Hargreaves (1998: 128) has argued: ‘Users must play a role in shaping the direction of educational research as a whole, not just in influencing a local project in which they happen to be involved’.

Thus, approaches to user engagement are intricately bound up with efforts at many levels to improve the quality and relevance of social science research. This is important because it helps to explain why user engagement can raise concerns about political influence amongst some researchers, how discussions of user engagement need to be sensitive to research genres and their different conceptions of knowledge; and how issues of scale (local versus national, individual versus institutional) cannot be overlooked. It also underlines the way in which research is part of broader change processes happening across public services: namely, increasing emphasis on user-led and personalized services based on the vision of ‘giving people who use services power over what they use [as] part of a general trend towards providing services that prioritize independent living, choice and inclusion’ (Bartlett 2009: 7).

Connecting with Wider Knowledge Production

Another important context for user engagement is the evolution of ideas about knowledge generation within democratic societies. It has been clear for some years that the nature of knowledge production is changing in many areas of science, technology and social science. As Gibbons et al. (1994: 19) argued in the early 1990s:

A new form of knowledge production is emerging alongside the traditional, familiar one [. . .]. These changes are described in terms of a shift in emphasis from a Mode 1 to a Mode 2. Mode 1 is discipline-based and carries a distinction between what is fundamental and what is applied [. . .]. By contrast, Mode 2 knowledge production is transdisiplinary. It is characterized by constant flow back and forth between the fundamental and the applied, between the theoretical and the practical. Typically, discovery occurs in contexts where knowledge is developed [. . .] and put to use.

While these ideas were developed largely in the context of science and technology, their ramifications for knowledge production within social sciences such as education have not gone unnoticed. Publications on educational research, for example, have argued that Gibbons et al.’s work ‘alerts us to the fact that research and researchers are not the universal sources of knowledge’ (Hodkinson and Smith 2004: 155) and ‘gives us an idea of how research and practice can inform each other and support each other’ (Furlong and Oancea 2005: 8). The underlying point is that developments such as user engagement cannot be isolated from the fact that ‘the contexts of knowledge production and use in society are diversifying and new models of research are being developed to respond to these challenges’ (Furlong and Oancea 2005: 6).

User engagement needs to be understood not just as a way of addressing concerns about quality and relevance, but also as a way of academic research learning from the many other modes and forms of knowledge generation and mediation going on beyond the academy. In this way, user engagement raises interesting and important questions about research design, project leadership and researcher and user capacity building. As will become clear in later chapters, the varying time scales and priorities of different players involved in the research process can present considerable challenges for project management. Project management thus becomes the weaving together of different forms of expertise, priorities and time scales across a variety of sites. This, like other aspects of user engagement, has significant capacity-building implications for researchers, users and mediators.

Enhancing Research Use and Impact

Alongside issues of research quality and knowledge generation, user engagement also needs to be seen as closely connected with questions of research use and impact. The last 15 years have seen significant changes in the expectations and demands placed upon social research. The growth of evidence-based or evidence-informed policy movements internationally, coupled with concerns over the accountability of public services expenditures, have increasingly put the spotlight on issues of research impact and research utilization. As a report on the topic from the ESRC describes:

In parallel with the ESRC’s continuing commitment to impact assessment, the Government in recent years has also placed increasing emphasis on the need to provide evidence of the economic and social returns from its investment in research. This trend was reinforced in the Warry report [. . .] to the (then) DTI in 2006, which recommended that the Research Councils ‘should make strenuous efforts to demonstrate more clearly the impact they already achieve from their investments’.

(ESRC 2009a: 2)

Such imperatives have, of course, played out very obviously in national systems for the assessment of research quality. Within the UK, for example, the new Research Excellence Framework is anticipated to place a higher value on scholarly and practical impacts rather than just focusing on research outputs. The intention is that ‘[s]ignificant additional recognition will be given where researchers build on excellent research to deliver demonstrable benefits to the economy, society, public policy, culture and quality of life’ (HEFCE 2009). There are also proposals for ‘a substantive input into the assessment of impact by representatives of the users, beneficiaries and wider audiences of research’ (HEFCE 2010: 3). The challenges of measuring impact have been acknowledged for many years, with McIntyre (1998: 196) suggesting that ‘whether or not it is possible, it is certainly necessary’.

As well as these very real changes in the material conditions of social science research, there have also been important conceptual developments within the social sciences in terms of understandings of research impact and use. Put simply, research use has moved from being a largely peripheral concern to become ‘a very significant practical and intellectual challenge’ (Nutley et al. 2007: 3). The utilization of research and evidence in policy and practice settings has emerged as a legitimate topic for theoretical and empirical inquiry. Understandings of the processes and factors involved have become more diverse and nuanced. More linear ideas of research dissemination and knowledge transfer have been challenged by more complex notions of research utilization and knowledge mediation, brokerage and translation. As the authors of a recent paper entitled ‘Why “knowledge transfer” is misconceived for applied social research’ argue:

Research on how research outputs inform understanding and get used suggest that use is best characterized as a continual and iterative pr...