This is a test

- 374 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book addresses issues in the philosophy of art through the lenses of the three broad areas of philosophy: metaphysics, epistemology, and axiology. It surveys many important and pervasive topics connected to a philosophical understanding of art.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Philosophy of Art by David Boersema in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION TO THE PHILOSOPHY OF ART

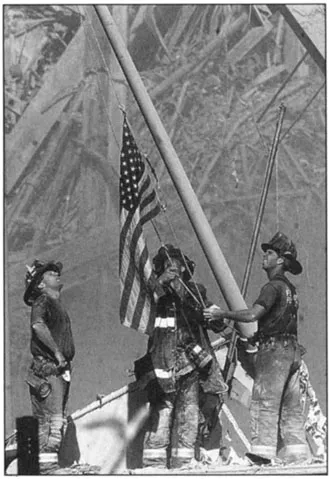

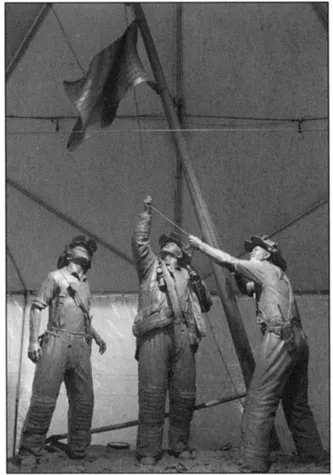

During the tumultuous days following 9/11/2001, a photojournalist, Tom Franklin, took a photograph of three firefighters raising a flag at Ground Zero (Figure 1.1), where the World Trade Center in New York City had been hit in a terrorist attack. The three firefighters were Dan McWilliams, George Johnson, and Billy Eisengrein; all three were white males. After seeing this photograph, Bruce Ratner, president of a New York City real estate management company, wanted to memorialize the heroism and meaning of that day by commissioning an honorific bronze statue. Ratner consulted with various fire department officials and with Ivan Schwartz, the president of StudioEIS, in Brooklyn. Collectively, they decided to pay homage to the firefighters and rescue workers of the day and chose to employ “artistic license” and have a commemorative statue created that would depict three generic firefighters, portraying what were believed to be characteristically white facial features, black facial features, and Hispanic facial features. A clay model of the statue was unveiled in December 2001 (Figure 1.2) and was met with immediate criticism. Some people claimed that choosing to portray three ethnically identified faces was an act of political correctness. The photograph was of a real event, they said, capturing the heroics of three particular individuals, and the proposed statue was a betrayal of and insult to the three individuals who were originally photographed. Those who defended the proposed statue claimed that the statue was not meant to be merely a three-dimensional version of that photograph; it was meant to be a symbolic statement honoring not only the three specific firefighters but also all those who engaged in acts of heroism that day. Yet others claimed that the statue was not even only about acts of heroism that day but was, rather, about heroism generally, or perhaps about the virtue of sacrifice or the vigor of the American spirit. Because of the uproar, the full statue was never made.

1.1 Ground Zero Spirit photo by Tom Franklin. Courtesy AP Photo/Thomas E. Franklin/The Record (Bergen County, NJ).

1.2 Clay model of proposed 9/11 statue. Courtesy AP Photo/Robert Spencer.

This simple case raises a great many questions and issues. For example, as has been at least hinted at, what was the purpose (or purposes) of creating such a statue? If the purpose of the statue was to be honorific, exactly who or what was supposed to be honored? If the purpose was to honor specific people and a specific act via a work of art, how should that (best) be done? Should the work of art be a “mirror” of the people and event? What if the specific people that day (in this case, the three firefighters pictured) were all wearing hats; would it have been inappropriate for the work of art (in this case, a statue) to omit hats? What if the flag that was being raised had been hanging in a limp and droopy way; would it have been inappropriate for the work of art to portray it more fully, say, in a more unfurled manner? So in what ways, and why, should the statue have been strictly a three-dimensional duplication of the photograph?

Obviously, those who created the clay model did not think their task was simply to make the photograph into a three-dimensional sculpture. They made decisions about what to include and exclude—in part, what to portray and depict—as well as how to do so. For that matter, the photographer also made decisions when taking the photograph. He framed the picture in a certain way. He could not include everything that was happening at that moment in that setting in the photograph. He decided, for example, to include the flag in the picture, to have the firefighters a certain size and position relative to the background (for instance, he could have focused only on the flag or included only the heads of the firefighters). He could have waited a bit longer before snapping the photograph or taken it slightly sooner than he did. He could have aimed the camera at a different angle than he did. The point is that the photograph itself was not merely a “mirror” of the situation; it, too, involved deliberation and decision making, not only at that moment of taking the picture, but certainly also later, in the process of developing the picture.

Some questions, then, are about the content of the photograph and of the clay model. What was actually, or intended to be, portrayed or depicted? What did the content of the photograph and of the clay model represent (if anything)? In addition, how did the content portray or depict whatever it was that it portrayed or depicted? That is, did it do so by accurately and precisely duplicating the situation, or were other factors involved? Also, why was the content portrayed or depicted, and why was it done so in the way it was? Was it, in fact, to honor specific people in a specific act? Even if that were the case for the photograph, why should it be the case for a separate work of art, the proposed statue?

Besides questions about the content of the photograph and of the clay model, there are, as already noted, questions about the relationship between the photograph and the model. With respect to art, these questions arise not only for this particular case but also for such relations generally. Some specific object or event could be the inspiration or cause for someone to create a work of art. Think of how many examples of art you are aware of that were inspired by, say, the birth of Jesus, or by the Madonna and Child.

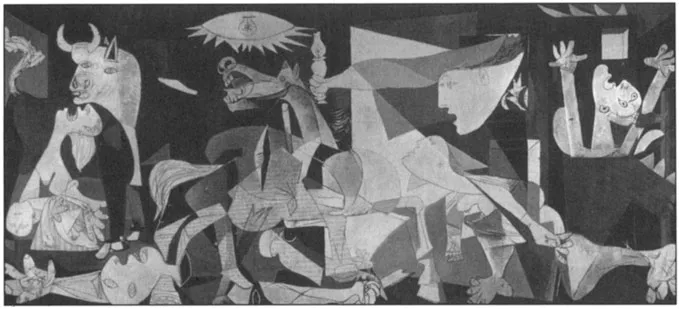

If we focus only on the issue of something being represented in an artwork, we can ask, what is an artist doing via the creation of a work of art? For instance, what was Pablo Picasso doing in and with his painting Guernica (Figure 1.3), or Johannes Brahms in and with his Third Symphony? Assuming that something is represented in these works, what the artist was doing involves issues of what was represented, how it was represented, and why it was represented. What was Picasso doing? He was representing a particular historical event, but also much more. Indeed, in representing the event, he necessarily focused on certain aspects of it and not on others. Likewise, he expressed or communicated or attempted to evoke (or provoke) by means of certain colors, textures, shapes, and so on. As with what he represented, how he represented was a matter of selectivity on his part. In addition, why he represented what he represented and why he did it in the way(s) he did (for example, why he chose black, white, and gray rather than a rainbow of colors) matter. To truly understand what these phenomena are (that is, the object Guernica as well as the phenomenon that is the creation of the object Guernica), all these questions involving representation—what, how, and why—are pertinent. Of course, those same issues are relevant to the 9/11 photograph and statue, as well as to art in general.

1.3 Guernica by Pablo Picasso, copyright © 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

WHAT IS PHILOSOPHY?

This book is an introduction to the philosophy of art, including to some of the kinds of questions and issues that were just noted. As an introduction, it will raise a number of issues and touch on a number of topics, but, because it is an introduction, it will only survey these issues and topics. Any one of them—for instance, the issue of representation in art or the issue of the relationship between art and morality—could be, and has been, the subject of full-length books. In addition, many issues and topics will only be mentioned but not discussed in detail (and others will not even be mentioned at all). For example, with respect to the social dimensions of art, a lot has been written on the nature and meaning of art museums, asking, for example, how and why certain works of art receive a special status by being placed in a museum (but in this book the effect of museum placement will not be mentioned at all beyond right here). Nonetheless, in this book we will survey many important and pervasive topics connected to a philosophical understanding of art. The first topic within the philosophy of art—as opposed to, say, the history of art or the sociology of art—is the philosophy aspect. Before looking at philosophy of art, then, we first need to look at what philosophy is (or what a philosophical approach to art is).

The word philosophy comes from two Greek words, philo, meaning “love,” and sophia, meaning “wisdom.” Philosophy, then, is the love of wisdom, and a philosopher is a lover of wisdom. However, both love and wisdom themselves carry various meanings. Here love is taken to mean both an activity and also an attitude. To love something or someone is to act in certain ways with respect to that thing or person. It is to act for the care and well-being of that thing or person. Wisdom here also means both an activity and an attitude. To be wise is to know things, but it is not “merely” having knowledge. Knowing lots of information, being very good at games like Trivial Pursuit, is not the same thing as being wise. Knowledge of facts is important, but it is not enough.

One sense of wisdom, then, at least for the early Greek philosophers, was the search not merely for a lot of factual information but for what they saw as “first principles.” Principles refer not to specific cases or instances but to basic, fundamental, unifying notions or conditions. For example, a moral principle, such as “Murder is wrong,” is meant to apply not just to a few particular situations but, rather, universally. Likewise, a natural principle (what today we would call a scientific law), such as the law F = ma (force equals mass times acceleration), is said to apply not just to a few particular situations but, rather, universally. So by seeking wisdom, philosophers were looking for underlying, unifying principles. By speaking of first principles, they meant the most basic, fundamental principles.

Wisdom also involves actively seeking knowledge, as well as analyzing and evaluating it. It is an openness toward asking questions, with the view that every good question has an answer, but also that every good answer generates another question. One way to characterize a philosophical attitude is to say that it treats what is common as uncommon and what is uncommon as common. That is, it asks questions about those things that seem obvious and common, and treats them as if they are strange and in need of explanation. The result is that one sees them in a new light and sees the underlying assumptions one had about them. At the same time, a philosophical attitude treats uncommon things as common; that is, it looks for connections and relationships between those things that seem to be strange or unfamiliar and things that one already knows or understands. This is a philosophical attitude and acting philosophically (not merely speaking one’s opinions or views).

Philosophy usually proceeds in two ways: analyzing and synthesizing. The first notion of analyzing means asking, What is X? where X might be knowledge, truth, beauty, goodness, personhood, freedom, and so on. These seem to be very broad and abstract notions, but more concrete ones would be notions such as person or mind or rights. For example, the question, What is a person? has very practical and important ramifications. One is connected with the issue of abortion. It is undeniable that a human fetus is human, because being human is a biological concept. A human fetus has human DNA. The more important social and moral issue is whether or not (or in what important ways) a human fetus is a person. It is persons that we claim have rights, for instance, or are part of our moral concerns. So the issue of abortion rests in large part on whether or not a human fetus is a person. What is a person? then, is a conceptual, philosophical question. Although it sounds abstract at first, in fact answers to it have very practical and important consequences.

The way philosophers address questions and analyze concepts is often by looking for necessary and sufficient conditions for something. A necessary condition for something is a condition that the thing must have in order for it to be what it is. For example, a necessary condition for something to be a mother is that the thing must be female. To give another example: a necessary condition for someone to be elected president of the United States is that the person must be at least thirty-five years old. A sufficient condition for something is a condition that the thing could have (but would not necessarily have) that would “be enough” for that thing to be what it is. For example, it is not necessary to have ten dimes in order to have a dollar (you could have, say, a hundred pennies or four quarters), but it is sufficient; as long as you have ten dimes, you have a dollar. Another example: being a citizen of Oregon is sufficient for being a citizen of the United States; as long as you are a citizen of Oregon, you are a citizen of the United States. Some conditions are said to be both necessary and sufficient. For instance, having a certain chemical structure (say, being H2O) is both necessary and sufficient for something to be water. Or there might be a set of conditions that are said to be “jointly” necessary and sufficient. For instance, if something is a bachelor, that thing needs to be an unmarried adult human male. All of the four conditions (being unmarried, being adult, being human, and being male) are necessary, but none by itself is sufficient. Together, however, they are said to be jointly necessary and sufficient.

The reason philosophers care about necessary and sufficient conditions is that these are said to be important components for understanding what something is and for distinguishing what something is. Take the case of what it is to be a person. One might ask whether being a human is the same thing as being a person. This is simply a way of asking if there could be nonhumans that we would consider to be persons. Or philosophers will often ask about “borderline” cases. For instance, would we consider a human body with no brain in it to be a person, or if we could somehow keep a human brain alive and functioning without it being in a body, would that brain be a person? With respect to art, one might ask whether or not human intention is a necessary or sufficient condition for something to be art. Indeed, this is one topic that will be explored in later chapters. So questions of looking for necessary and/or sufficient conditions might appear to be abstract, but they are the thought experiments that philosophers use to try to clarify our concepts. (However, as we will see in later chapters, many philosophers claim that looking for necessary and/or sufficient conditions can itself be a mistake. Some things, they say, simply do not have necessary and/or sufficient conditions. A famous example comes from the twentieth-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. He used the example of games and claimed that there simply are no necessary and/or sufficient conditions for what makes something a game, because the term game is too loose and vague.)

Clarity about concepts is important and useful, but there is more to philosophy than analyzing things. There is also the second component of philosophy, namely, synthesizing. That is, we are concerned about how things make sense, broadly speaking. Being clear about things is good, but what does it all mean? Even if we could get a clear notion of what a person is, then what? One focus of philosophy is to help see how things fit together or relate to each other and to meeting our goals. Not only do we want to know the assumptions and presuppositions that we have about things, but we also want to know about the implications of believing certain things or acting in certain ways. We want to know how things cohere or hang together in meaningful ways. As the twentieth-century philosopher Wilfrid Sellars put it, we want to understand how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term. For example, if we were to say that a person is whatever (or whoever) has the ability to learn from its environment or to set personal goals or projects, then, if it turned out that some nonhumans do these things, would they be persons? Furthermore, if they were persons, would they, then, have rights? If so, what would this imply about how other persons would need to act or behave? These are the types of synthesizing questions that philosophers ask.

Philosophy’s content (that is, the answers to these sorts of questions, rather than its activity or attitude) is usually divided into three very broad categories: metaphysics, epistemology, and axiology. Metaphysics is the study of reality. This is not the same thing as science studying nature or social science studying human cultures. Rather, metaphysics asks about basic kinds of reality. For example, we take it for granted that there are things or objects in the world, such as trees and cats and water. But what about events? Are events real? An event, such as the falling of a leaf or the buttering of toast, is not the same “thing” as the physical leaf or the toast. That is, events are not equivalent to the objects involved in them. So are events real, and how are we to understand them? Another kind of example: are abstract “things” real? For example, are numbers real? When we write the numeral 2, we are writing down a representation of the number two. But when we erase that numeral, and it no longer exists, we do not erase the number two. If the number two is real, it is abstract and cannot be erased. So are numbers real? These are metaphysical questions; they are questions about what kinds of things are real, or are part of a good description of reality. (What is a person? is also a metaphysical question.)

As we will see in later chapters, such questions abound in the context of art. For instance, what, exactly, is a musical composition? Or: what is its metaphysical nature? Is it the notes written in a score? But of course, those notes themselves are abstract things. If we tear up a particular copy of the score, we do not destroy the score itself. And we certainly do not destroy musical notes. Furthermore, what about different musical performances of the “...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1: Introduction to the Philosophy of Art

- CHAPTER 2: The Nature of Art

- CHAPTER 3: The Artwork

- CHAPTER 4: The Artist

- CHAPTER 5: The Audience

- CHAPTER 6: Relationships Between Art and Society: Ethics, Education, Culture

- CHAPTER 7: Relationships Between Art and Science: Method, Understanding, Knowledge

- CHAPTER 8: Performing Arts

- CHAPTER 9: Visual Arts

- CHAPTER 10: Literary Arts

- Further Reading

- Credits

- Index