- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book captures the flavor and spirit of the highly trained and experienced practitioner as he goes about the task of organizing and conducting a group. It also captures the warmth and humanity of a professional who is deeply devoted to his patients, his profession and humanity at large.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section II

The Group-Analytic Group

Chapter 3

Diagnostics

The Formation of Groups for the Specific Purpose of Treatment

When forming a group specifically for treatment, patients who have no connection in life with each other are called together. Neither should they develop such contacts during treatment, or, for that matter, later. In these groups we are thus operating outside the life situation, with people who are strangers and share only the therapeutic situation. As our model we take the group-analytic group in its various forms.

The patient either comes on his own initiative or is referred to us by another doctor, often a psychiatrist. We meet him first either individually or in a group. Presently we shall deal in more detail with both methods of the initial interview.

Preliminary Information

Before we see the patient, we can elucidate a number of facts by questionnaires. This saves time and allows us to concentrate on the most important living features and impressions during the first interview.

Dynamic Use of Tests and Questionnaires

At this stage tests may be given. There are so many tests with which I am not familiar enough to judge them, but I have been favourably impressed with the MMI test. The thematic apperception test is also valuable, especially for comparing results after a period of treatment with the initial ones. I myself have had personal experience with the Rorschach test. I know this is under a cloud from the point of view of the statistically oriented psychologists because of being too unreliable or too much dependent upon the interpreter. Personally I think that this is inevitable. We can never be free from interpretation in the whole field of psychotherapy and psychopathology and to my mind the great merit of the Rorschach test lies in the fact that it is interpretative and yet furnishes some more objective data which form a check on one’s interpretation and guide it. The particularly interesting feature of the Rorschach test is that it stresses formal elements: whether the testee is impressed by large or small figures, whether he sees the obvious, whether he is attracted by colour or by movement and so forth. Such formal components are not usually sufficiently observed in the psychotherapeutic situation. Be that as it may, we will not enter further into the method of psychological testing, without in the least denying its potential value.

The questionnaires I have in mind have usually been specifically devised in view of the particular situation. Thus I used a questionnaire at Northfield which was specifically attuned to the military situation and the whole atmosphere of that hospital. Such a relatively simple questionnaire fulfils the following points: firstly the prospective patient can furnish all the objective data of his life circumstances, of his family, his profession etc. so that we have them complete and need not further question him. The second and main part of such a questionnaire is to get a preliminary picture of the patient’s attitudes, while it also makes him an active co-operator already in this phase. The patient is asked to write in his own way, briefly or in more detail, as he likes, on such points as: What are, from his point of view, the reasons for coming to see us? This includes of course questions as to what disturbs him or others; how he feels about all this himself. I then find it useful to ask him to write on his own ideas about his condition, his own theory as it were of his disturbance, and furthermore his expectations, in particular how does he think these conditions can change and how is this change to be brought about?

As already indicated, the patient enters in this way into an active discourse and contact with the therapist, and one can get a very good picture of his condition and his attitude. Naturally one will have to concentrate on these same points again when seeing him, but one will find that it is a great help to have studied the preliminary questionnaire and the ideas which the patient conveyed here.

Pictorial Profiles: A Tool for selection

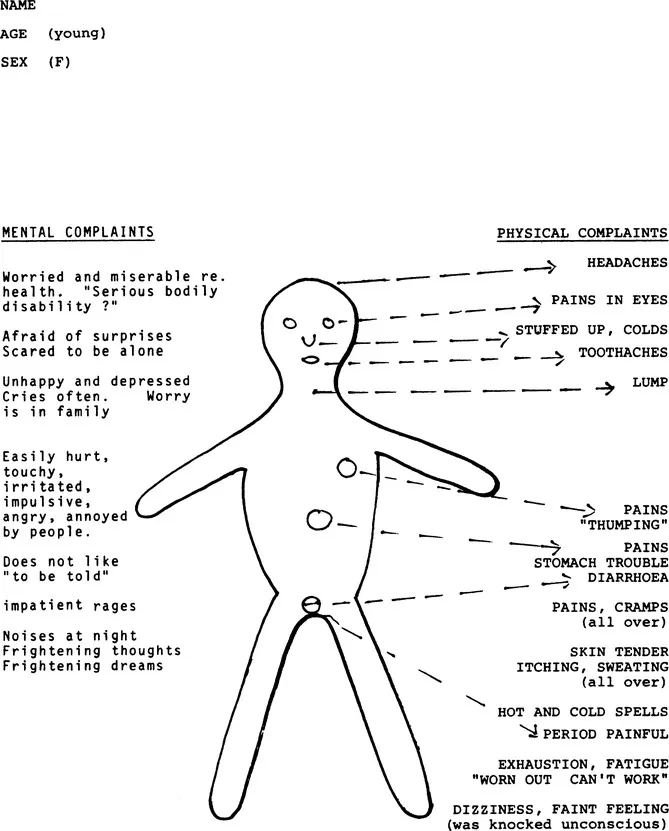

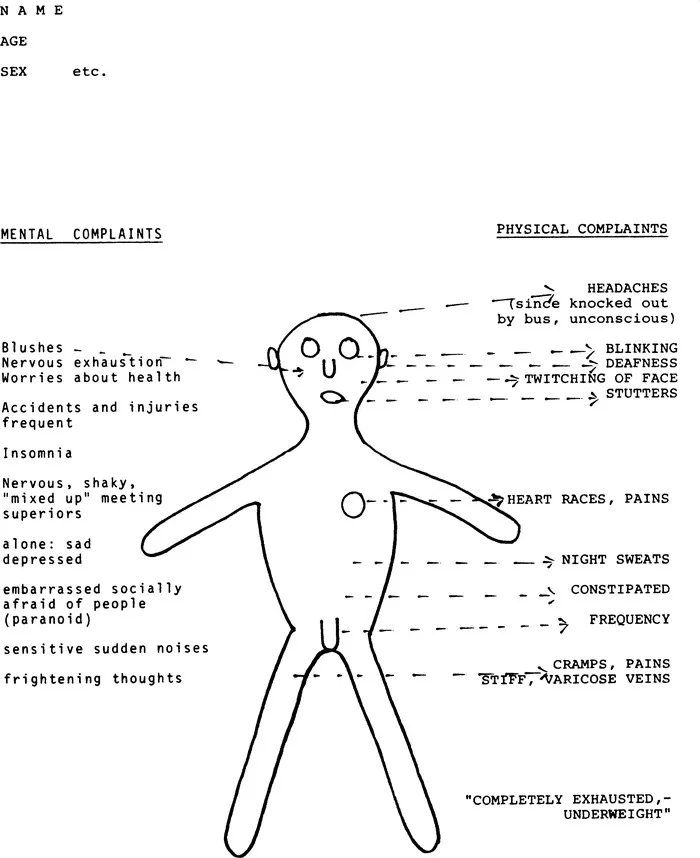

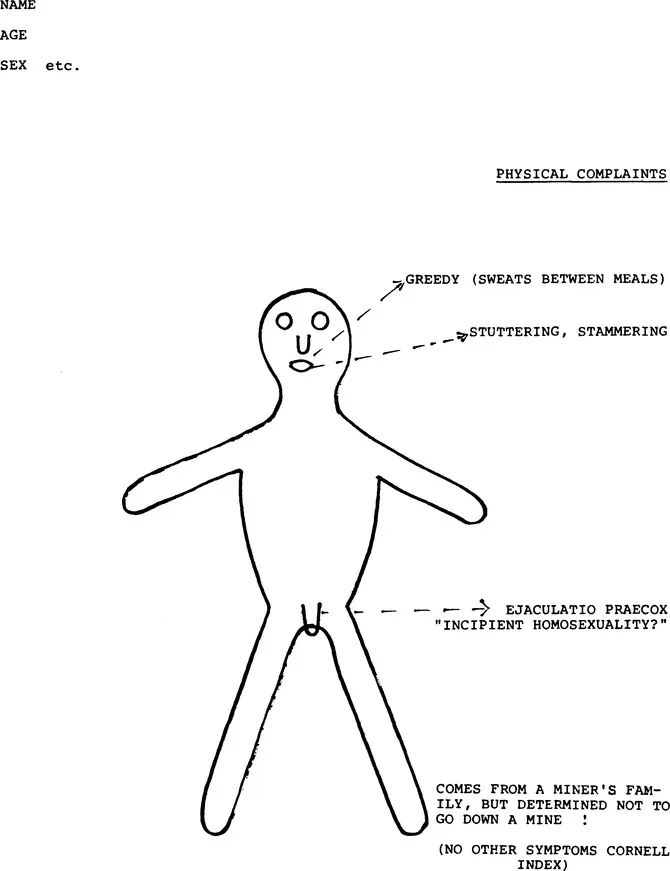

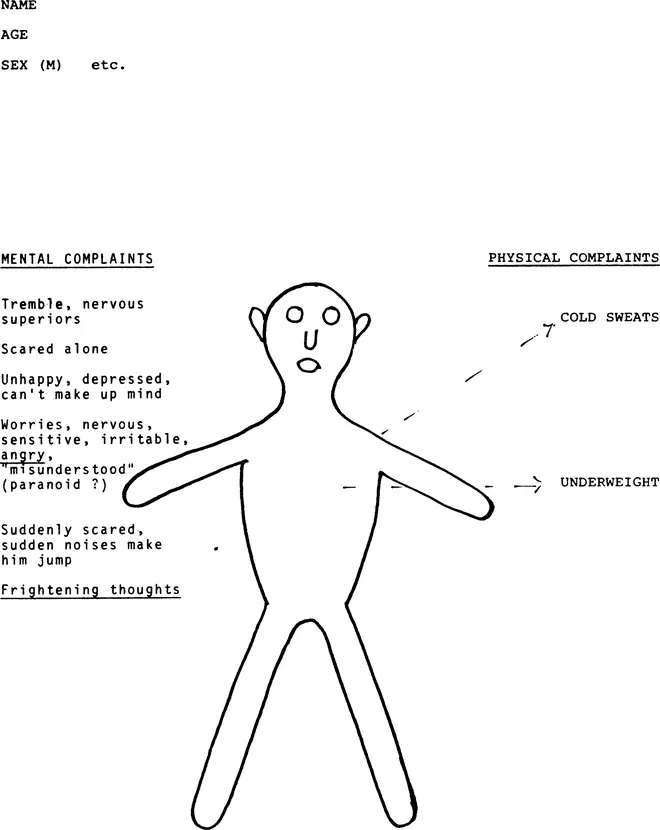

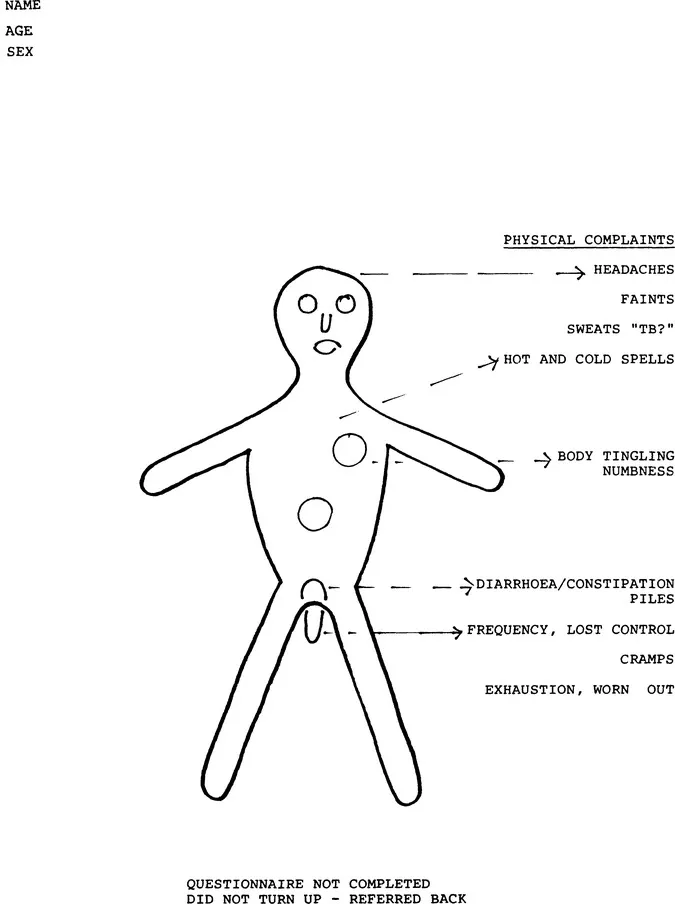

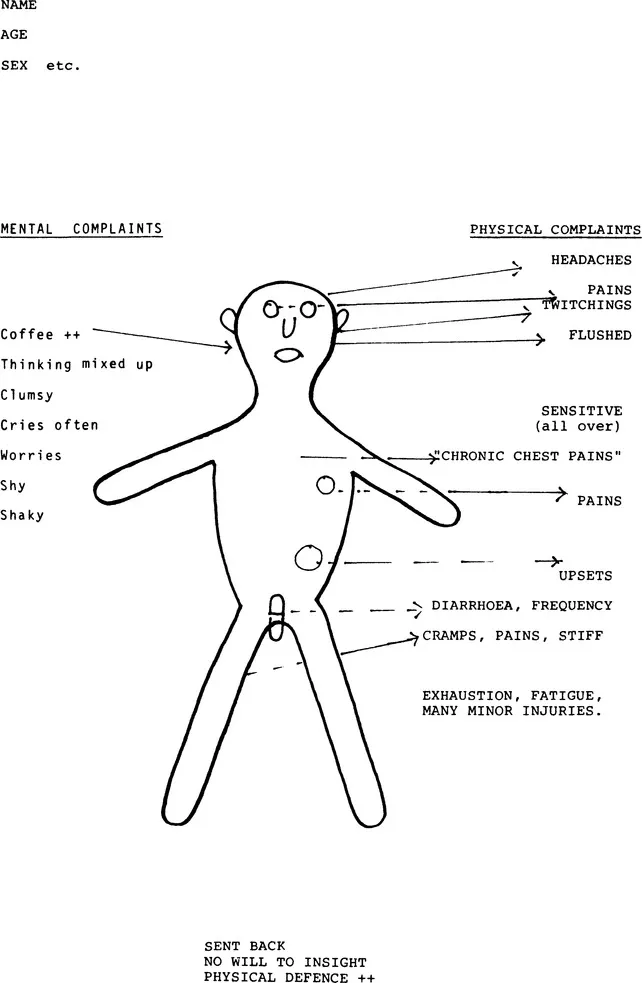

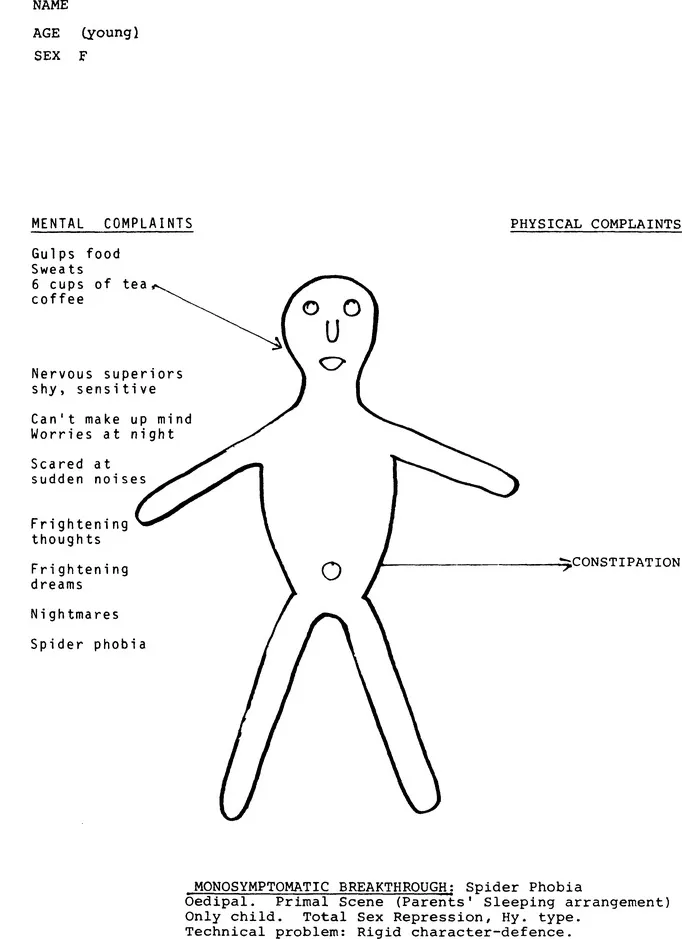

At the Out-Patient Psychotherapy Department of the Maudsley Hospital I used a different approach. The patients had, in a routine way, already been bombarded by various tests according to the different psychiatrists they had originally seen, the standard procedure being the Cornell Index. For this reason I did not add yet another questionnaire but found that I could use the Cornell Index information and translate it as it were into pictorial and more dynamic form. A number of examples will follow by way of illustration. Before seeing the patient, I went through the Cornell Index filled in by him and noted every point without exception in the way illustrated. I drew a little man or a little woman schematically and placed the complaints as expressed by him onto the different organs or regions of the body in a schematic way: I made a rough division, putting the complaints of a purely physical kind all on the right hand side in red, and those which in their very nature were mental or psychological — descriptions or complaints referring to mental functions — on the left side, in black, but have not followed these up systematically. More important are the qualitative characteristics. Complaints are to some extent a result of the questions raised by the Cornell Index Questionnaire, so is the wording of certain complaints, a product of standardised questioning on the mental side. The dynamically oriented psychiatrist, in particular the experienced psychoanalytically trained psychiatrist, will appreciate that in this way one gets a good picture of the type of anxieties, of the characteristic psychopathological constellation (paranoid, depressed etc) or the erotogenic zones which are outstanding, of the typical forms of anxiety and the levels of regression in terms both of id-impulses and ego mechanisms. For the rest, I hope that the illustrations will speak for themselves and I will have only to say little about each.

Figures 1 and 2 are fairly characteristic and represent the most frequent type of picture one gets.

Figure 3 by contrast is striking by the paucity of symptoms recorded.

Figure 4 by contrast to the following two, 5 and 6, shows a predominance of mental complaints and even the physical complaints are likely to be connected with anxieties, for instance, cold sweats, and particular worries, such as underweight.

Figures 5 and 6, on the contrary are heavily weighted on the physical side and seem to confirm that this is not a favourable symptom constellation for psychotherapy. The form of treatment recommended to a patient was not of course based on the questionnaire alone, but on the following interview and clinical judgement (apart from no. 5 who did not turn up for interview.)

Figure 7 in turn abounds in mental manifestations so that a certain detailed psychopathological formulation could tentatively be made, based in part on the interview; it was also noted that the patient showed very rigid character defences.

I thought it was worth publishing this method as it shows that even a static and mechanical questionnaire, (I am sure very complete to the statistician’s delight), can be transformed into a graphic and dynamic picture. Furthermore, it might well be that this technique, or a similar one, could be used for more systematic research in the conventional sense of this word.

The Initial Individual Interview

The initial interview will be greatly helped by the fact that contact has been made in writing and a preliminary picture of the patient been formed. First of all, one need not worry about those of the objective data which one already has; secondly, the enquiry into the patient’s attitude and the psycho-dynamic picture is guided as it were, but not prejudiced by what one has already noted. During this interview one can naturally observe the patient’s contact, his way of communication and understanding, his motivation — a very important element — his capacity for insight as he has already acquired it, or shows himself capable of acquiring it by the way he looks upon the intercommunication with the therapist as well as upon his defences. Facts will emerge which have to do with his current life situation, his family, his complexus. One will also be able to note any special problems which arise. After this, it should be possible to arrive at a preliminary interpretation of the case as follows

- Personality and psychodiagnostic dynamics

- Conflicts — predominantly intrapsychic or interpersonal

- Outlook and basis for resolution of these conflicts

- Special observations, if any.

This first individual interview can as a rule be confined to one occasion, though it is desirable not to allow any pressure to interfere and not to have a fixed limited time (such as a half hour or an hour) but to let it take the time it takes. It is however, not often necessary to extend such an interview beyond an hour or an hour and a half. I have occasionally settled the whole problem satisfactorily in such a ‘first’ interview, requiring no further therapy, though in these cases there was particularly good mutual contact. It might take two or more hours, but it can be done.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Assessment After Treatment

At the end of treatment it will be possible to have certain statistical data about his attendance, regularity, or the opposite and the duration of the treatment; important factors will be his mode of leaving, his condition as compared to the initial one, the changes, which were observed, the reasons for them, and particularly the changes in his intimate plexus. Again special observations can be made after some time; it is valuable to have a follow-up, based on the observations in the various networks in which the patient moves, as well as his own statements.

Introductory Interview in a Group

We come now to a less usual but exremely interesting method, namely an introductory interview in a group setting. I shall go into this in some detail because of what I think to be its considerable interest. When seeing patients from the start together in a group, the general assumption is that these patients are expected to carry on as a group. By a method described in more detail later, there is a preliminary selection. Experience has shown that one needs about twelve apparently suitable candidates in order to form a group of eight. Let us assume that this selection, this sorting out, has already taken place, and that we start with a group of eight with the intention of carrying on with this group. The question arises as to whether the conductor of this initial group, this introductory, diagnostic group intends to carry on with it, or to pass it on to someone else, say, a registrar. The approach varies accordingly, although the basic elements ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Introduction by Max Rosenbaum

- Section I Group-Analytic Orientation

- Section II The Group-Analytic Group

- Section III The Conductor

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Group Analytic Psychotherapy by S.H. Foulkes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.