Chapter 1

Introduction

Margaret Kernan, Elly Singer and Rita Swinnen

What this book is about

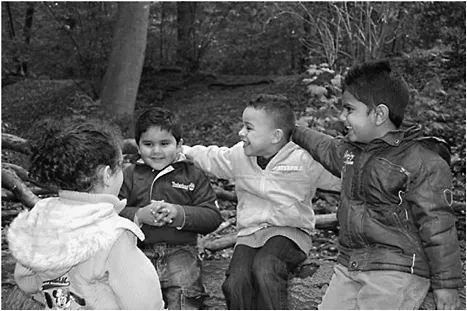

This book is about young children’s relationships and children’s active participation in their social world. An important premise is that the experience of positive social relations and the development of positive identities are core dimensions of children’s well-being and sense of belonging (Brooker and Woodhead 2008; Bruner 2004; Dunn 2004). These are important concerns at a time when organized early childhood education and care settings have become significant sites of young children’s daily lives in many contexts worldwide. Child rearing is increasingly acknowledged as a collaborative endeavour between families and early childhood education and care institutions (OECD 2006). Peer relationships are also a high priority for children because of the fun and pleasure they derive from being in the company of other children. This is often most evident in play.

Cross-cultural and historical studies show that non-parental care of young children was initially not designed to serve the needs of children (Lamb et al.1992). Non-parental early childhood arrangements have proliferated because parents need to be employed and cannot simultaneously care for their children. With economic need driving the demand, early childhood arrangements have been used in various countries to serve a variety of goals. These goals range from equal opportunities for males and females to acculturation of immigrants, rescuing young children ‘at risk’ from impoverished homes whose parents were considered incapable of effective socialization, and the provision of better educational opportunities for children from disadvantaged families (Lamb et al. 1992; Singer 1992). However, at the beginning of the 21st century, there is a growing trend to view early childhood education and care as a means to enrich the lives of all young children and their parents. Additionally, learning and thinking in the early years are increasingly being conceptualized as social activities. The growing influence of socio-cultural theories (Vygotsky 1978; Rogoff 2003) and relational pedagogy is reflected in the positioning of relationships and interactions at the heart of early childhood education and care curriculum frameworks in different regions throughout the world. For instance, in the national curriculum frameworks guiding practice in Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand and the countries of the UK, the role of exploration and play in young children’s learning is stressed. Furthermore, young children’s emotional security is seen as the result of the quality of the relationships between children, teachers and parents.

Phenomena such as urbanization, new patterns of migration and increased heterogeneity in societies, changing family structures and work practices are all impacting on children’s everyday social experiences at home, and in early childhood education and care settings. These developments have created opportunities and challenges that require early years practitioners to think and act in new ways. This is reflected in the various chapters in this book. The bringing up of young children outside the family raises new questions about the educational values on which the pedagogy in early childhood settings should be based. In many countries early childhood education and care is beginning to be viewed within a children’s rights framework due to the growing influence of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the associated General Comment 7 on ‘Implementing Child Rights in Early Childhood’ (see for instance, Chapters 4 and 5). The pursuit of social justice, respect for diversity and ethical practices are emerging as core values in early childhood pedagogy (see Chapters 8 and 9). Increased attention is being paid to the development of respectful, partnership relations between early years practitioners and families and children; migrant parents’ expectations and experiences of early childhood education and care settings (Adair and Tobin 2008; Prott and Hautumm 2005; Chapter 10); to identity and belonging (see Chapter 6); and to young children’s active participation and the experience of citizenship (Kjørholt 2008). In these changing conditions, early childhood education and care assumes an important role in building and sustaining respectful communities.

The topic of ‘young children’s relationships’ relates in this book to children’s interpersonal relations with peers, younger and older children, and adults in their everyday lives, at home, and in the whole host of early childhood care and education settings, ‘organized’ or less ‘organized’, where young children from birth to 8 years spend their time. It encompasses understandings and experiences of nurturance, care and learning in interactions and interpersonal relations; conflicts and negotiation; pleasure and rejection; friendships and play; group phenomena; independence and interdependence; and identity and belonging. Our particular interest in this book is in children’s ‘lived through experience’ (Valsiner 2007) of social relations in the niche of their everyday lives, acknowledging the cultural and contextual diversity of childhood and children’s lives globally – and therefore the many forms that social relationships may take, and the meanings that may be attributed to them (see Chapters 3 and 7). Our aim in this book is also to explore questions relating to social justice and community building through the lens of young children’s relationships in early childhood education and settings.

Children’s perspectives on their social relationships

Relationships and interactions, particularly interactions between early childhood practitioners and children, have been identified as a key element of process quality in early childhood education and care (Howes and James 2002) and significant for positive outcomes for children (OECD 2001; Shonkoff and Phillips 2000). Consequently, in recent decades considerable attention has been paid to researching and describing optimal adult–child relationships in early childhood pedagogy (Ebbeck and Yim 2008; Papatheodorou and Moyles 2009). Somewhat less attention is being paid to understanding young children’s relationships and interactions with other children in terms of what children ‘get’ from relationships (Rubin, Bukowski and Parker 2006). Relationships and friendships matter to children. As noted by Dunn (2004: 3) ‘We are missing a major piece of what excites, pleases, and upsets children, what is central to their lives even in the years before school, if we don’t attend to what happens between children and their friends’. The priority children give to their peer relationships, often encapsulated in ‘playing together’, is evident when young children are consulted about what is important in their everyday lives in early childhood education and care settings (Clark and Moss 2001; Corsaro 2004; Moromizato 2008). It is also apparent in the narratives of older children when they recall their early childhood (Torstenson-Ed 2007).

Distinguishing different types of social relationships

In early childhood education and care settings young children enter into two different types of relationships: those formed with adults and those formed with peers (Singer and de Haan 2007). From a very young age children differentiate between these two types. They rely on adults for emotional support, security, practical help, cognitive challenges, moral rules and guidance. Parents and teachers structure young children’s

lives in many ways. They let them participate in routines and rituals; they organize the material environment and time; they teach ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’. Parents and teachers guide young children often with an ‘invisible’ hand with help of structured patterns of behaviour, time structures and an organized physical environment. With peers, young children enter into more equal relationships. Young children are attractive social partners for each other because of shared interests, excitement and joy in play activities. When young children meet each other on a regular basis they co-construct shared meanings, expectations and rituals. They develop friendships and a peer culture. According to Corsaro (2004) young children co-construct in recurrent interactions shared meanings, humour, conflict strategies and games in which they incorporate elements of the adults’ culture. In the peer group they appropriate, in their own way, what they understand and learn from their teachers and parents. For teachers it is important to understand both types of relationships. They should make room for the rituals and expectations peers co-construct among themselves alongside the rituals, routines and rules of the adults in the home and the centre. See Figure 1.1.

To support children in adapting to the social life in the childcare group, teachers need to be aware of different levels of social dynamics. Firstly, there is the level of the dyadic relationship of the teacher and the individual child: that is, the interaction of the teacher with an individual child (Chapter 2). Research based on the attachment

theory shows that availability and sensitive responses of the teacher to the child’s signals fosters the emotional security of the child. Especially for new children in the group, physical proximity to the teacher is often very important. Later on they rely more on social referencing while they are playing alone or with peers at some distance from the teacher (Hoogdalem et al. 2008). They are regularly looking at the teacher – ‘is she still taking care of me?’ Young children read the emotional expressions on the teacher’s face –‘is what I do okay?’ Teachers often react to the child’s social referencing by giving short verbal and non-verbal signs. So they monitor the child’s behaviour from a distance and create psychological closeness without being physically nearby.

Secondly, teachers help children to adapt to the social life in the group at the level of dyadic peer relationships and subgroups. From the moment children develop the motor skills to move around freely, they show interest in other children. During free play they spend much more time with peers than with a teacher (Singer and de Haan 2007). With peers, young children quickly learn that they are challenged to improvise and to cope with misunderstandings and disagreements. Most children like to play with peers. But in every group there are children who have problems adapting themselves to group life. Without the support of the teacher these children become the isolated and neglected children of the group. Sometimes the impulsive children with many conflicts become the scapegoats of the group and are blamed for all the

aggressive actions and crying that may occur during peer conflicts (Singer and de Haan 2007). In peer relations children discover that they have influence and that they can play and experiment with power – in a positive way by helping other children and showing leadership behaviour, and in a negative way by bullying peers. For instance a girl, almost four years old, the oldest of the group and well liked by the teachers in a Dutch early childhood education and care setting, had discovered that she could kick a younger boy without being observed by the teacher; when the boy reacted by hitting her, he was blamed and not she. It took some time before the teachers discovered the real ‘perpetrator’ and could regulate and discuss this behaviour with the children.

Thirdly, there is the level of dynamics in the whole group and between subgroups (Vaughn and Santos 2008). At this level teachers manage the children in order to foster posit...