A diagnosis of cancer is not an isolated event, but rather a poignant moment in an often-lengthy time-line. In some cases, that timeline begins with a set of risk behaviors that make an individual vulnerable to cancer. The next step may be a routine screening test to identify the presence of cancer, or perhaps a proactive effort by the individual to seek help in the face of emerging symptoms or warning signs, often followed by additional tests to characterize the precise nature of the cancer diagnosis. Following a diagnosis, people face treatment decisions, sometimes with the option of enrolling in a clinical trial. At each of these points in the timeline, attitudes play a role in determining both patients’ and physicians’ intentions and behavior. Patients’ attitudes toward risky and healthy behaviors contribute to the likelihood that they will become vulnerable to cancer; their attitudes toward screening tests and help seeking contribute to the likelihood of catching the cancer at an early stage (if at all); their attitudes toward various treatment options contribute to their course of treatment and ultimate prognosis; and their attitudes toward clinical trials and genetic testing contribute to the likelihood of their participation in each. Even at the point of diagnosis, physicians’, patients’, and family members’ attitudes toward disclosure of diagnostic information can contribute to the extent and type of information patients receive about their cancer. In this chapter, we review the broad and sometimes inconsistent literature on attitudes in the context of cancer, with an effort to organize this research area and identify opportunities for further progress.

Conceptual Issues

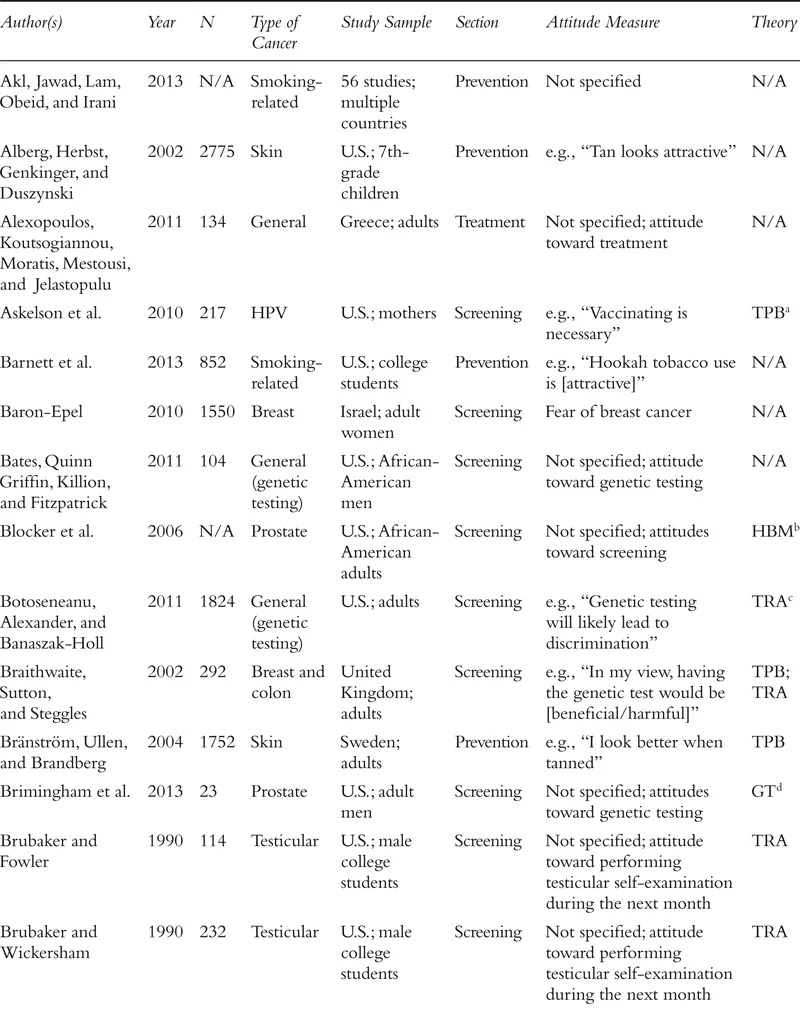

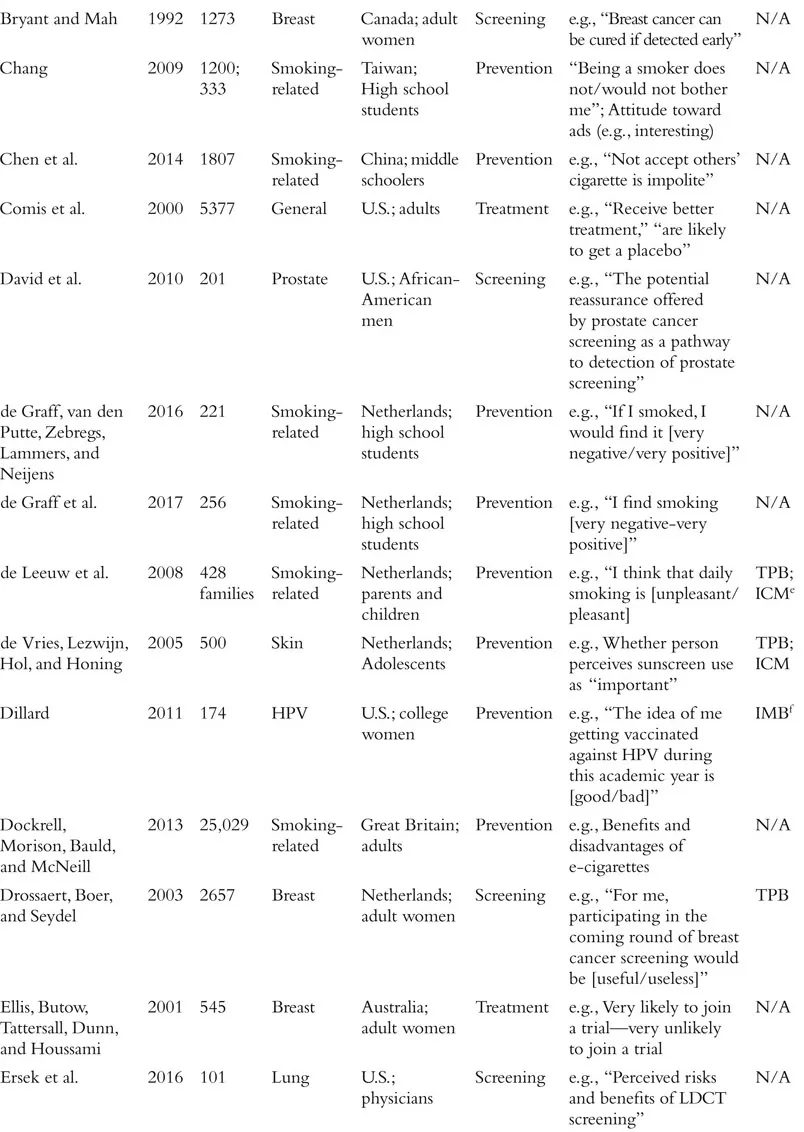

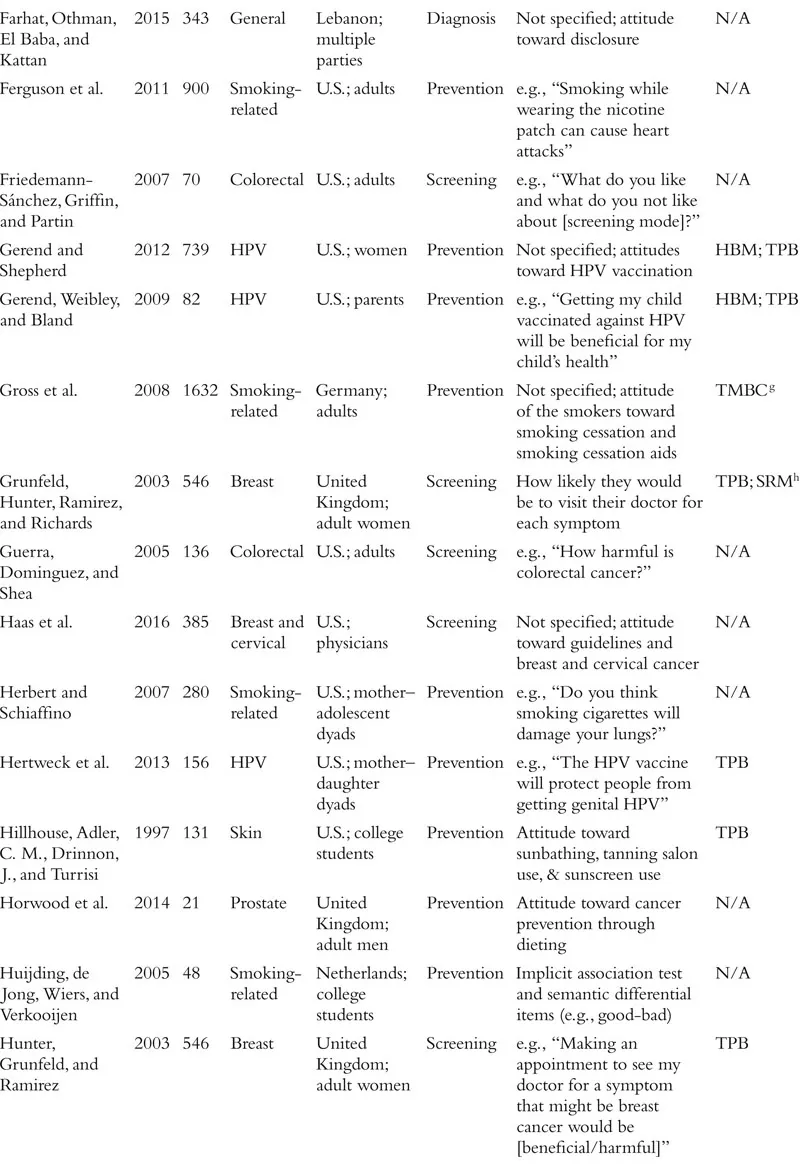

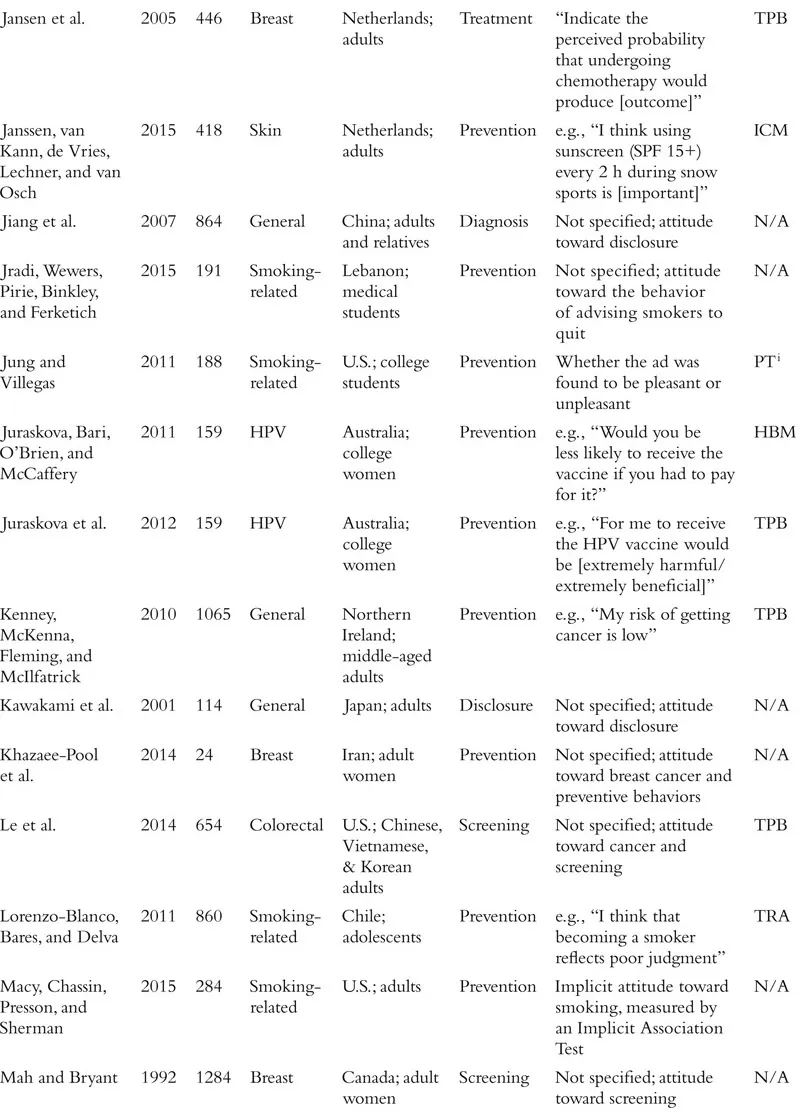

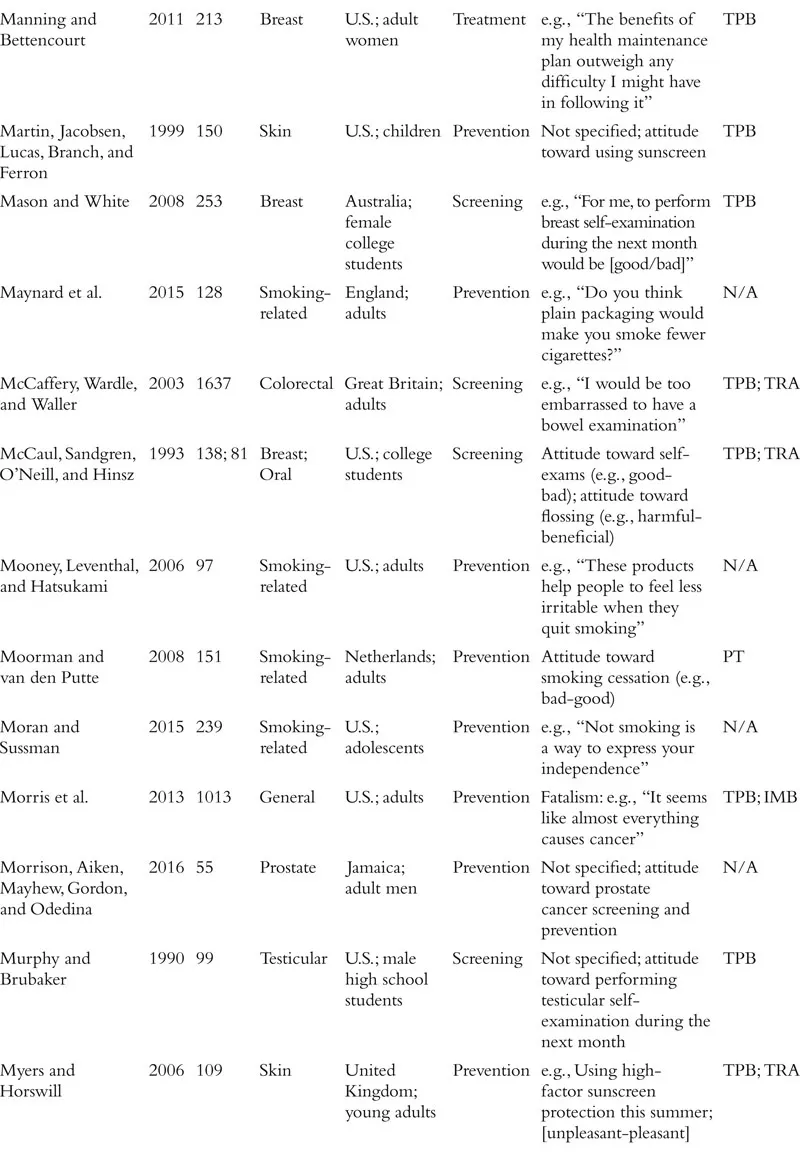

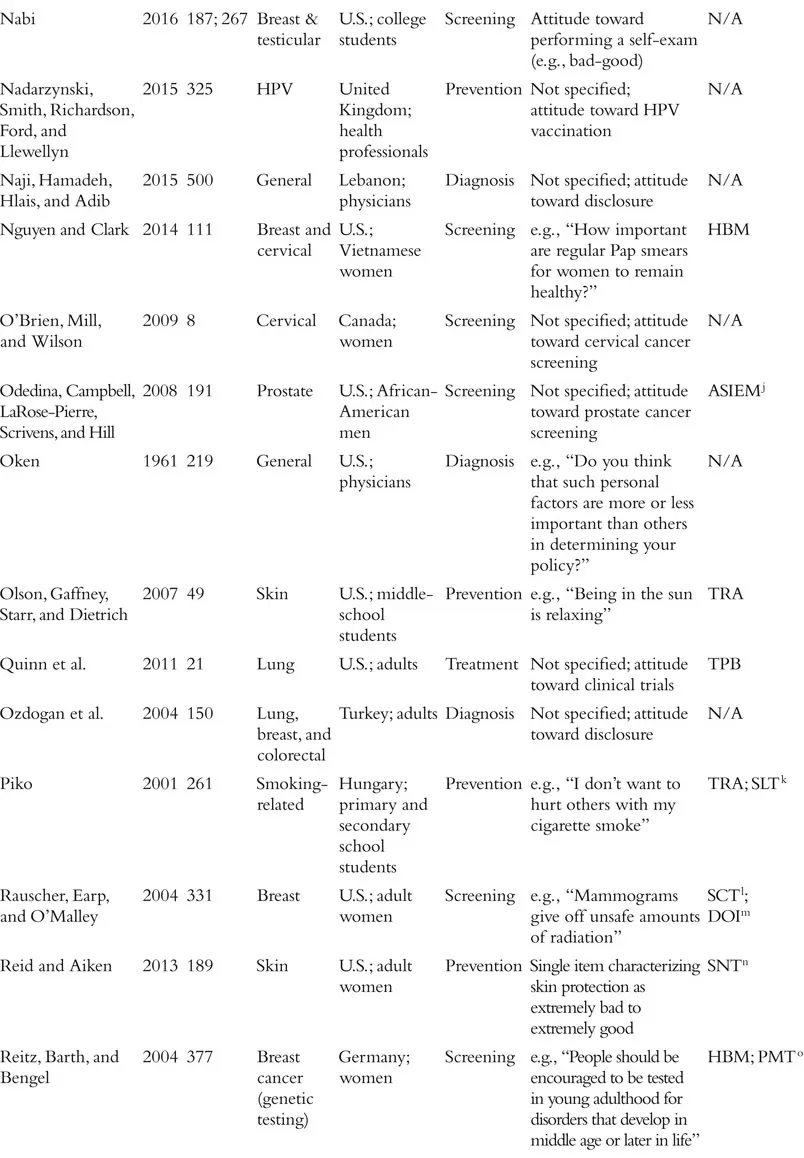

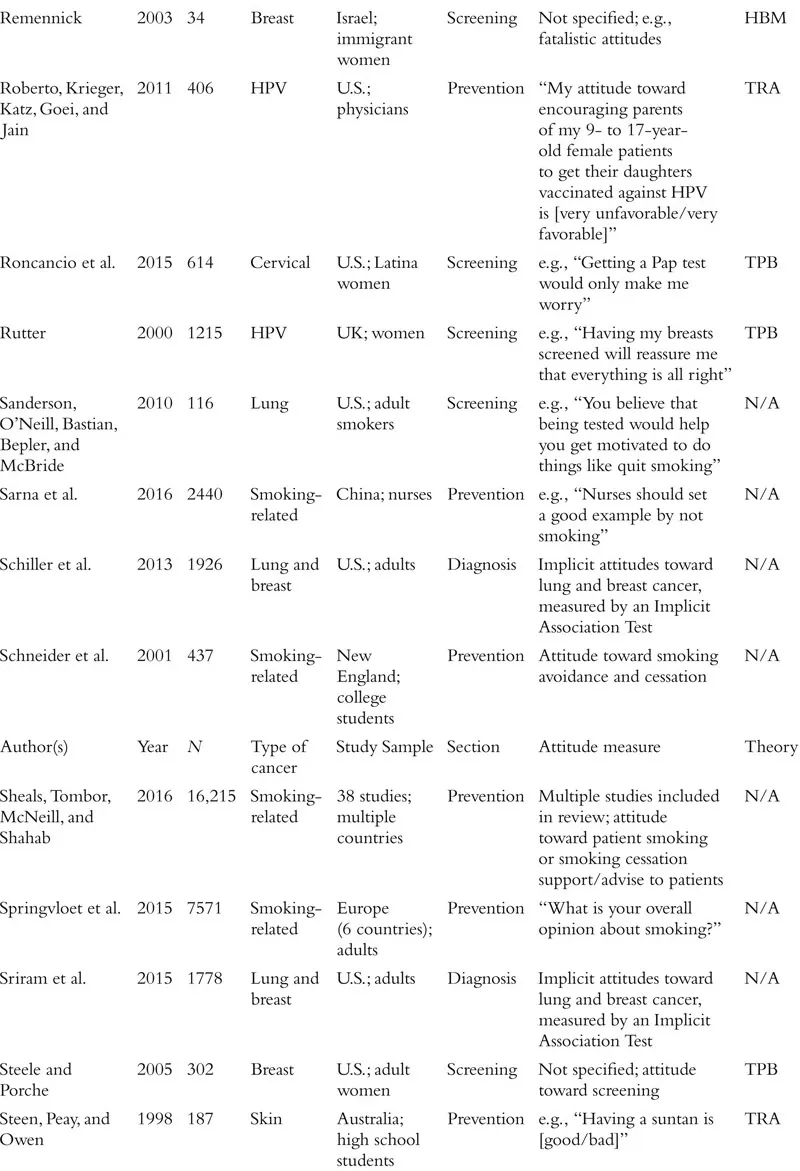

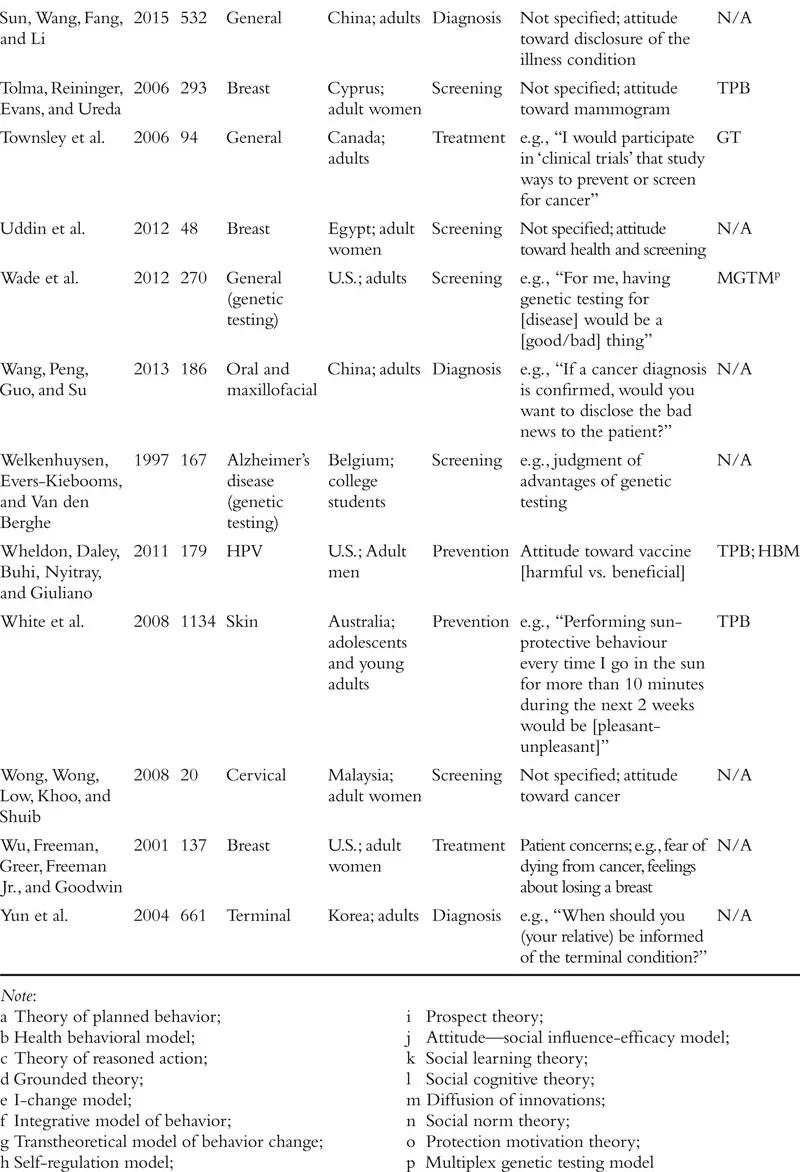

The field of attitudes research defines an attitude as a valenced evaluation of some entity (e.g., Ajzen, 2001; Albarracín, Johnson, Zanna, & Kumkale 2005; Albarracín et al., this handbook). For example, in the context of cancer, people may have relatively positive or negative attitudes toward cancer-preventive behaviors (e.g., wearing sunscreen, exercise), cancer detection methods (e.g., mammograms, going to the doctor, genetic testing), cancer diagnosis (e.g., disclosure or concealment of diagnosis), and cancer treatments (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy), among other cancer-relevant attitude targets. Although this definition is clear in concept, the measurement of attitudes within the literature on cancer often violates this strict definition. In fact, researchers who study cancer seem to use the term “attitudes” quite loosely, with apparent definitions including the accepted definition above, but also broad beliefs and feelings about cancer and cancer-relevant behaviors, perceptions of benefits of a course of action, risk perceptions, knowledge about a specific type of cancer, and even anticipated emotional responses to various outcomes. The specific measures used in each study we review is included in Table 1.1. We approach our review with the goal of providing an overview of the literature on cancer-related attitudes as defined by the relevant authors or researchers. That is, if a naïve reader searched for research on “attitudes” and “cancer,” what would that reader find? We return to definitional and conceptual issues at the end of the chapter.

Table 1.1 Summary of Included Studies

We also note that much of the research on attitudes in health contexts, and specifically in the context of cancer, has been guided by the theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991, 2012, 2014; Ajzen, Fishbein, Lohmann, & Albarracín, this handbook). This theory posits three determinants of intentions to engage in a given behavior: subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and attitude toward the behavior of interest. Although many studies stretch the definition of an attitude proposed by the TPB, a large proportion of studies that include a measure ostensibly assessing attitudes are grounded in this theory. As we proceed with our review of the literature on cancer-related attitudes, we will note the studies that took inspiration from the theory of planned behavior or its predecessor, the theory of reasoned action (Madden, Ellen, & Ajzen, 1992; see Table 1.1). Other studies reference additional theories of health behavior, including the health belief model (Rosenstock, 1974; Janz & Becker, 1984; e.g., Blocker et al., 2006) and the behavioral model of health (Anderson, 1968; e.g., Nguyen & Clark, 2014), among many others that we note in the table.

Another theory with clear relevance to our review is terror management theory (Greenberg & Arndt, 2012). Specifically, the terror management health model (TMHM) addresses the complex links between mortality salience (i.e., awareness of one’s eventual death) and health-related behavior (e.g., breast exams, wearing sunscreen; Goldenberg & Arndt, 2008). Given that a majority of people in one study saw cancer as equivalent to a death sentence (Moser et al., 2014), people who ultimately find themselves facing a cancer diagnosis (or even just a potential diagnosis) may try to reduce or manage the salience of their own mortality by engaging in health-focused behavior, as the TMHM suggests. In some cases, mortality salience prompts healthy behavior, as people presumably attempt to reduce thoughts of death by leaning into death-delaying attitudes and behaviors. In other cases, mortality salience prompts unhealthy behavior, particularly when people’s self-esteem or identity is strongly associated with the relevant behavior (e.g., smoking, Arndt et al., 2009; Hansen, Winzeler, & Topolinski, 2010; tanning, Arndt et al., 2009; Cox et al., 2009). Although attitudes are only rarely assessed in studies of the TMHM, their role in mediating behavior change is certainly implicated (e.g., see McCabe, Vail, Arndt, & Goldenberg, 2014). For example, a study of smoking attitudes found a crossover interaction between mortality salience and the degree to which participants’ self-esteem was contingent on smoking, such that mortality salience made attitudes more positive for those with smoking-based self-esteem and more negative for those without (Hansen et al., 2010).

In addition to broad theories of health behavior, research on the persuasive power of fear appeals (i.e., messages that induce fear in recipients with the intention of persuading them toward attitude change; see Johnson, Wolf, & Maio, this handbook) points to several principles that guide successful attitude change interventions, including in the context of cancer. Regarding broad effects of fear appeals, two meta-analyses have examined the effects of fear appeal messages and found that fear appeals are reliably effective for changing attitudes (in Witte & Allen, 2000, r = .15; in Tannenbaum et al., 2015, d = .20). More relevant to this chapter, numerous studies have focused on the effects of fear-inducing messaging on cancer-related behavior specifically (e.g., testicular self-examination, Morman, 2000; sun protection, Cooper, Goldenberg, & Arndt, 2014; breast self-examination, Ruiter, Kok, Verplanken, & Brug, 2001). Although fear appeals are generally effective for increasing cancer-preventive behavior and screening and decreasing cancer-promoting behavior, they sometimes back-fire. Fear appeals can have “side effects” that may reduce positive attitudes toward health-protective behavior or increase negative attitudes toward harmful health behavior, including fatalism and hopelessness (Cho & Salmon, 2006).

A Review of the Literature on Cancer-Related Attitudes

The literature on attitudes in the context of cancer addresses many types of cancer, with the most commonly studied types including those with the highest incidence in the population: breast cancer, skin cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, and lung cancer. Some studies address cancer generally without specifying a particular type, and others address behaviors that might increase one’s risk for several types of cancer (e.g., smoking, poor diet). As highlighted in the opening of this chapter, we organize our review of the literature around various stops on the cancer journey rather than by type of cancer. Specifically, we review research on the role of attitudes in cancer prevention (focusing narrowly on skin protection, smoking behavior, and HPV vaccine uptake, for reasons noted in what follows), cancer screening and help seeking (including work on attitudes toward genetic testing), disclosure of information about cancer diagnoses, and cancer treatment (including participation in clinical trials). We focus our review on relatively recent research, although we address older findings when useful or necessary to fully cover an area of study. All papers central to our review are presented in Table 1.1.

Cancer Prevention

Researchers have studied the role of attitudes in predicting a variety of cancer-preventing behaviors. Some behaviors directly protect people from developing a specific type of cancer (e.g., applying sun-screen to decrease one’s chance of developing skin cancer), whereas the effect of other behaviors is more indirect (e.g., diet, alcohol consumption). Given the very broad set of behaviors that can increase or reduce one’s cancer risk (in the words of the singer Joe Jackson, “everything gives you cancer”), we will focus our review on three groups of behavior that have received considerable empirical attention and are closely related to cancer risk: skin protection/tanning, smoking-related behaviors, and HPV vaccine uptake. See other chapters in this handbook for coverage of substance use (White, Chan, Kostigyna, Emery, & Albarracín, this volume), diet (Matta, Dallacker, Vogel, & Hertwig, this volume), and exercise (Hagger, this volume).

Skin Protection

Much of the research on attitudes’ role in cancer prevention has focused on skin cancer prevention, typically in the form of skin-protection behaviors like avoiding the sun, wearing sunscreen, or covering the skin, or cancer risk behaviors like tanning outside or in tanning beds. This research has revealed that in general, people who have a more positive attitude toward tan skin are more likely to spend time in the sun and intentionally go out into the sun, whereas those who have a more positive attitude toward skin protection are more likely to engage in skin-protective behaviors like applying sunscreen. Turning first to attitudes toward skin cancer risk behavior (e.g., tanning outdoors or in a salon, having tan skin), the link between attitudes and behavioral intentions is quite consistent. One study surveyed college students in the U.S. and found a link between attitudes toward tanning behavior and intentions to engage in such behavior (Hillhouse et al., 1997), and a study of high school students in Australia similarly found a link between positive attitudes toward having a tan and sun exposure intentions (Steen et al., 1998). In a sample of Swedish adults, positive attitudes toward being tanned and being in the sun were associated with both risk and protective behaviors, including spending time in the sun, intentional tanning, vacationing in a sunny place, and using less sun protection (Bränström et al., 2004). The effect sizes in these studies tend to be quite large and robust.

Similarly, numerous studies have confirmed that a positive attitude toward sun-protection behaviors (e.g., avoiding the sun, using sunscreen) predicts both sun-protection intentions and behavior. For example, Dutch adolescents who had more positive attitudes toward sunscreen use, wearing skin-protective clothing, and seeking shade were more likely to report engaging in those behaviors (de Vries et al., 2005), and both young adults in the UK and Dutch adults going on a ski holiday who had more positive attitudes toward sunscreen use reported stronger intentions to use sunscreen and more frequent use of sunscreen (Janssen et al., 2015; Myers & Horswill, 2006). Similarly, positive attitudes toward skin protection among U.S. middle school students were associated with reduced likelihood of sunburn (Alberg et al., 2002). In a sample of Australian adolescents and young adults, attitudes toward sun-protection predicted intentions to engage in protective behaviors but did not predict sun-protective behavior after accounting for intentions (White et al., 2008). Interestingly, in the study of Australian high school students mentioned in the previous paragraph, attitudes toward minimizing sun exposure also predicted sun exposure intentions, but not as strongly as did attitudes toward hav...