![]()

Part I

Foundations

Part I of this book introduces educational design research, and lays the foundation for Parts II and III. Chapter 1 describes motives and origins for design research, characterizes the approach, and examines it in light of various research goals. Chapter 2 describes the kinds of contributions to theory and practice that can be made by educational design research, and offers four extended examples. After discussing lessons learned from literature, especially the fields of instructional design and curriculum development, a generic model of the educational design research process is presented in Chapter 3.

![]()

Chapter 1

About educational design research

What sets educational design research apart from other forms of scientific inquiry is its commitment to developing theoretical insights and practical solutions simultaneously, in real-world (as opposed to laboratory) contexts, together with stakeholders. Many different kinds of solutions can be developed and studied through educational design research, including educational products, processes, programs, or policies. This chapter provides an introduction to educational design research. After a definition and brief description of the main origins of educational design research, characteristics and outputs of this approach are discussed. Following attention to the rich variation in educational design research (e.g. in focus, methods, and scope), three prevailing orientations are described: research conducted for, on, or through interventions. The chapter concludes with considerations of what distinguishes educational design research from educational design, and from other genres of inquiry.

Motives and origins for educational design research

Educational design research can be defined as a genre of research in which the iterative development of solutions to practical and complex educational problems also provides the context for empirical investigation, which yields theoretical understanding that can inform the work of others. Its goals and methods are rooted in, and not cleansed of, the complex variation of the real world. Though educational design research is potentially very powerful, it is also recognized that the simultaneous pursuit of theory building and practical innovation is extremely ambitious (Phillips & Dolle, 2006).

Educational design research is particularly concerned with developing what Lagemann (2002) referred to as usable knowledge, thus rendering the products of research relevant for educational practice. Usable knowledge is constructed during the research (e.g. insights among the participants involved) and shared with other researchers and practitioners (e.g. through conference presentations, journal articles, professional development workshops, and the spread of interventions that embody certain understandings). Because educational design research is conducted in the naturally occurring test beds of school classrooms, university seminar rooms, online learning environments, and other settings where learning occurs, these studies tend to require methodological creativity. Multiple methods are often necessary to study phenomena within the complex systems of authentic settings, with the goal of attaining higher degrees of ecological validity. In an ecologically valid study, researchers apply methods such as observations or interviews in the real-life situation that is under investigation (Brewer, 2000). The external validity of a study (the ability of a study’s results to be generalized) stands to be increased when conducted under real-world conditions. The remainder of this section provides a brief historical perspective and describes the two main motives of seeking relevance and robustness. Later in this chapter, additional attention is given to the notion of generalizability (see ‘Main outputs of educational design research’).

Linking basic and applied research

Research is often classified as being either basic or applied. In basic research, the quest for fundamental understanding is typically shaped by using scientific methods to explore, to describe, and to explain phenomena with the ultimate goal of developing theory. Basic research generally follows what has been characterized as an empirical cycle. De Groot (1969) described this cycle through five phases: observation (data collection); induction (formulating hypotheses); deduction (making testable predictions); testing (new empirical data collection); and evaluation (linking results to hypotheses, theories, and possibly new studies). In contrast, applied research features the application of scientific methods to predict and control phenomena with the ultimate goal of solving a real-world problem through intervention. Applied research generally follows what has been characterized as a regulative cycle, described by van Strien (1975, 1997). The five phases of the regulative cycle are: problem identification; diagnosis; planning; action; and evaluation. Although basic and applied research approaches have historically been considered mutually exclusive, many argue that this is not the case, as described next.

For over a hundred years, social science researchers and research critics, including those in education, have struggled to define the most appropriate relationship between the quest for fundamental understanding and the quest for applied use. Psychologist Hugo Münsterberg (1899) and educational philosopher John Dewey (1900) both spoke of a linking science, which would connect theoretical and practical work. Taking these ideas further, Robert Glaser (1976) laid out the elements of a psychology of instruction, calling for a science of design in education. Thirty years later, Donald Stokes (1997) provided a fresh look at the goals of science and their relation to application for use, in his highly acclaimed book, Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation.

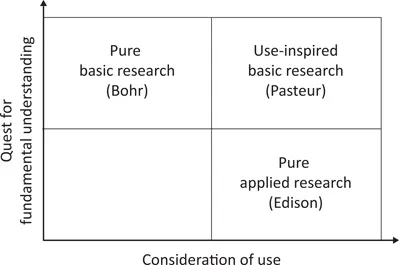

Use-inspired basic research

Stokes (1997) lamented the artificial separation of basic and applied science, suggesting instead a matrix view of scientific research as illustrated in Figure 1.1. Whether particular researchers are seeking fundamental theoretical understanding or whether they are primarily concerned about practical applications of research determines their placement within the matrix. To illustrate, Stokes described the research conducted by Niels Bohr as typical of pure basic research. Bohr was a Nobel-Prize-winning Danish physicist who sought fundamental knowledge about the structure of the atom. His work was not concerned with practical application of that knowledge. In sharp contrast, Stokes described the research conducted by Thomas Edison as typical of pure applied research. Edison was an American inventor who sought to solve practical problems by creating innovative technologies. He expressed little interest in publishing his research findings or contributing to a broader scientific understanding. Linking the motives of these two scientists, Stokes described the research of Louis Pasteur as typical of use-inspired basic research. Pasteur was a French chemist and microbiologist who sought fundamental knowledge within the context of solving real-world problems such as the spoilage of milk and treatment for rabies. Stokes left the quadrant which represents research that neither seeks fundamental understanding nor considers practical use blank. However, critics of educational research have argued that too much educational research belongs in this sterile quadrant because it contributes little to understanding or to use (cf. Reeves, 2000).

Figure 1.1 Pasteur’s quadrant

Source: Stokes, 1997

Stokes (1997) called for much more focus on ‘use-inspired basic research’ of the kind conducted by Pasteur. Stokes also questioned the popular assumption that basic research inevitably leads to the development of new technologies. He argued that technological advances often permit the conduct of new types of basic research, thus reversing the direction of the basic to applied model. For example, the development of powerful computers and sophisticated data analysis software has allowed scientists as diverse as astronomers and neuroscientists to apply computational modeling as an effective method for advancing their research agendas (Farrell & Lewandowsky, 2018; Shiflet & Shiflet, 2006). As discussed in the following section, others have argued that the relationship between basic and applied research is interactive.

Robust and relevant educational research

Schoenfeld (2006) pointed out that the advancement of fundamental understanding and practical applications can be synergistic. Using the Wright brothers’ work to develop a flying machine to illustrate, he described how theory influenced design and vice versa (p. 193):

Theory and design grew in dialectic – nascent theory suggesting some improved design, and aspects of design (even via bricolage) suggesting new dimensions to the theory. As they matured, aspects of each grew independently (that is, for example, theory was capable of growing on its own; at the same time, some innovations sprang largely from their inventors’ minds rather than from theory). Yet, the two remained deeply intertwined.

Educational design researchers have characterized their work as belonging to Pasteur’s quadrant (cf. Roschelle, Bakia, Toyama, & Patton, 2011). We view educational design research as a form of linking science, in which the empirical and regulative cycles come together to advance scientific understanding through iterative testing and refinement during the development of practical applications. Through such a synergistic process, educational design research stands to increase both the robustness of its theoretical implications and the relevance of its innovative products.

Robust design practices

The need for increased, reliable, prescriptive understanding to guide robust design of educational products, processes, programs, and policies has been stressed in the literature for several decades, most notably in the field of curriculum (e.g. Stenhouse, 1975; Walker, 1992; van den Akker, 1999). Several reasons for this can be identified. First, research is needed to provide grounding that can inform initial or subsequent design decisions. Edelson (2002) refers to three classes of decisions that determine a design outcome: problem analysis (what needs and opportunities the design will address); design procedure (how the design process will proceed); and design solution (what form the resulting design will take). Decision making within each of these classes can be greatly facilitated by research, conducted within the project, and/or through analyzing the findings of other studies. Second, planning for interim testing that allows designs to respond accordingly is needed to increase the chances of ambitious and complex interventions to succeed. Innovative design is typically ill-specified, and cannot be conceived of at the drawing table alone (van den Akker, 1999). Planning for and embedding formative research into design trajectories emphasizes the principle that design decisions should not all be made up front, and acknowledges the expectation that research findings will responsibly inform the development. Third, embedding substantial research into the design process can contribute greatly to the professional development of educational designers. Given that huge numbers of the world’s learners are exposed to the products of educational designers (e.g. from curriculum institutes and textbook publishers), their levels of expertise are not inconsequential. Burkhardt’s (2009) article describing important considerations of strategic design stressed that designers must learn from mistakes (as he says, “fail fast, fail often”) and that research is essential to feed such learning. Burkhardt also stated the need for more people trained in educational design research (he used the term ‘engineering research’) to design and develop robust solutions.

Relevant and robust from a scientific perspective

A symposium titled “On Paradigms and Methods: What To Do When the Ones You Know Don’t Do What You Want Them To?” was held at the 1991 American Educational Research Association annual meeting to examine how relevant theoretical understanding can be obtained. Among other approaches, design experiments were considered. Building on that discussion, Collins (1992) and Brown (1992) each published landmark papers, which have often been credited as primary catalysts for launching the genre of educational design research. Brown (1992) recommended design experiments based on the convictions that: theory informs design and vice versa; research on learning must be situated in the contexts where that learning actually takes place; and multi-pronged approaches are needed to influence learning (e.g. teacher expertise, learner activities, classroom materials, formative assessments) because educational settings are inherently complex systems. Collins (1992) persuasively argued for a design science of education, where different learning environment designs are tested for their effects on dependent variables in teaching and learning. This view emphasizes the interactive relationship between applied and basic research, by stressing the role of theory in informing design, and the role of design testing in refining theory. Collins (1992) also highlighted the problem inherent in much educational research whereby an innovation as designed in a laboratory and the innovation as implemented in real classrooms is – more often than not – quite different.

Brown (1992) offered a rich description of her work on metacognition, reciprocal teaching and reading comprehension, which pointed to the importance and challenges of developing theoretical understanding that is based on relevant findings. She described the tensions that she had experienced between the goals of laboratory studies and the goals of educational innovations, as well as the challenges inherent in integrating innovations in real-world classrooms. In addition, she described how the laboratory work informed her classroom observations and vice versa. She stressed the value of cross-fertilization between laboratory and classroom settings for enriching understanding of the phenomenon being studied, and clarified that “Even though the research setting has changed dramatically, my goal remains the same: to work toward a theoretical model of learning and instruction rooted in a firm empirical base” (Brown, 1992, p. 143). The publication of these papers in 1992 spurred increased attention to the need for theory to inform design and vice versa (Cobb, Confrey, diSessa, Lehrer, & Schauble, 2003); the need to understand learning as it naturally occurs and, specifically, what that means for how we shape education (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000); and the need for classroom interventions to fit into the dynamic and the complex systems in which they are implemented (Hall & Hord, 2014).

Relevant from a practical perspective

The relevance of educational research has to do with its connection to practical applications. Educational research has long been criticized for its weak link with practice. This may be a function of the fact that educational theories are only rarely confirmed by evidence that is unambiguous and/or thorough (De Corte, 2000). Some have argued that educational research has not focused on the problems and issues that confront everyday practice (Design-Based Research Collective, 2003). Others have lamented the lack of useful knowledge produced by research that could help inform the development of new innovations and reform (Bevan & Penuel, 2018; van den Akker, 1999). The different languages spoken and values held by researchers and practitioners, respectively, have also been the topic of empirical investigation as well as critique (de Vries & Pieters, 2007). Further, the weak infrastructure supporting the research-based development function in education has been cited as problematic (McDonnell, 2008). In addition, the reward systems in place for both researchers and practitioners are generally incompatible with meaningful researcher–practitioner collaboration (Burkhardt & Schoenfeld, 2003). Based first on literature review and later validated through research, Broekkamp and Hout-Wolters (2007) clustered these issues into four main themes: (a) educational research yields only few conclusive results; (b) educational research yields only few prac...