THE STARTING POINT for the work of the aphasia centre is the experience of living with aphasia. People who have aphasia describe the dramatic and often traumatic nature of its onset, the sense of bewilderment and fear which loss of language engenders, its impact on their lives, families and work, their day-to-day struggles with interaction, conversation and communication, and the profound and often long-term adjustments which must be made. The multi-faceted nature of aphasia demands a flexible, integrated approach to therapy and support.

The service which is evolving at the aphasia centre draws upon a number of different influences, both within aphasiology and beyond, and aims to achieve balance and integration in what is offered to clients. In this chapter, we describe some of these formative influences, focusing particularly on those which come from outside the domain of traditional aphasiology.

Influences within aphasiology

At the aphasia centre, clients are offered a range of options for therapy that draw upon diverse sources and traditions. Some of these are rooted in well established, theoretically based therapeutic approaches to language impairment. For example, in the 1980s, the therapy programmes offered at the centre were profoundly influenced by the rapid developments within cognitive neuropsychology. Cognitive neuropsychologically based interventions continue to play a major role in contemporary aphasia therapy, and to grow in sophistication. They create opportunities for precise specification of language processing breakdowns and the development of targeted, rational interventions (Byng et al, 1990; Thompson, 1998).

Clients attending the aphasia centre have the opportunity to analyse and work on their language impairment using these principles – often a prerequisite to disability-focused therapy. Because cognitive neuropsycho-logical methods are extremely well documented, they do not form the main focus of this book. However, the flexible combination of approaches forms a recurring theme throughout the text and in each chapter the integration of methods is discussed.

Other aphasiological traditions that have influenced the work of the centre include Holland’s work on functional communication (Holland, 1982), which is concerned with re-establishing the aphasic person’s use of effective communication in everyday contexts, and Total Communication, which focuses upon encouraging multimodality interactions (Lawson & Fawcus, 1999).

We try to be alert to new theoretical and clinical developments within established therapeutic traditions and to feed these into the work of the centre. For example, the practice of aphasia therapy has been influenced in the 1990s by new approaches to the modification of the language environment that surrounds the person with aphasia. Jon Lyon’s work on the use of drawing to enhance communication (Lyon, 1995) has extended the scope both of the functional approach and of Total Communication. Dr Lyon visited the centre in 1996 and worked with some of the clients. A research project on communicative drawing was being carried out at the centre at the time. This explored the potential of training people with severe aphasia to make use of drawing skills in backing up their communication (Sacchett et al, 1999).

Another major influence on aphasia therapy in the 1990s has been the work on training conversation partners developed at the Pat Arato Aphasia Centre, Toronto (Kagan, 1998). Strong links have been formed between the centres in London and Toronto. Working to extend and develop the skills of conversation partners, whether friends, family members, volunteers, students or professionals, has subsequently become a major focus of our work. Interventions that aim to reconnect people who have aphasia with their communities, and to support their caregivers (Lyon et al, 1997) have also influenced the practice of the centre. The philosophical underpinnings of what might be called a ‘systemic’ approach (that is, one which pays attention to the social networks of which the person with aphasia is a part, as well as to the language impairment itself) have been strengthened by the growth of literature concerning the ‘co-construction’ of aphasia:

As an injury, aphasia does reside in the skull. However, as a form of life, a way of being and acting in the world in concert with others, its proper locus is an endogenous, distributed, multi-party system. (Goodwin, 1995, p3l)

Of course, aphasiologists like Martha Taylor Sarno have long been concerned not just with the functional impact of aphasia but with the psychosocial effects upon the individuals who have it and the communities of which they are a part. Describing aphasia as a ‘social problem’, Sarno (1997) urges that increased attention be paid to its social ramifications. Her perspective encapsulates the therapies for living with aphasia which we are trying to develop at the centre:

National and regional aphasia associations must be strengthened, supported and encouraged to develop networks of aphasia advocacy groups in a cross-section of communities. In this regard we need to reach out to new aphasic patients, their caregivers, primary care physicians and health personnel at the community level and provide broad-based public education which informs and guides them to the best resources for support, acceptance, social interaction and community integration. (Sarno, 1997, pp676–7)

Influences beyond aphasiology: the impact of social model theory

While the influences described in the last section largely emerge from traditions within aphasiology, developments within disability theory have also had a major impact on the philosophy and practice of the centre. Readers with an aphasiological background may not be familiar with these concepts, and for this reason we are devoting the rest of this chapter to describing them in some detail.

Thinkers within the disability movement have reconceptualised disability in a way that profoundly challenges the assumptions and traditions of the rehabilitation culture and raises important questions for all those offering therapeutic services to people with aphasia. These concern four central issues:

•Alternative conceptualisations or models of disability

•The experience of disabled people

•Issues of empowerment and emancipation

•The relationship between impairment and disability.

In the following sections of this chapter we will outline these issues, then give an overview of how they influence the work of the centre.

Alternative models of disability

Disability theorists have shown that disability can be conceptualised in a number of different ways, some of which have more cultural power than others. Over the past decade, a number of different ‘models’ of disability have been described, each offering different constructions of disability. Reflection on these different models promotes understanding that disability is as much a cultural process as a biomedical state. Three contrasting models of disability are the medical model, the philanthropic model and the social model.

Medical model of disability

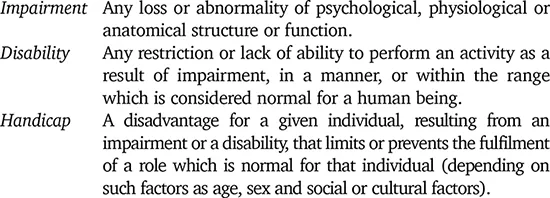

This model of disability underpins traditional approaches to the rehabilitation of disabled people and, as such, will be familiar to every aphasia therapist. Essentially, the medical model of disability focuses upon the functional inabilities and limitations of the disabled individual. Disability is seen as an inevitable corollary of impairment. Rehabilitation traditionally takes place within a medical context and culture, and is imbued with medical language and concepts. Medical model interventions aim to reduce the individual’s impairment and restore maximum function and independence. The medical model was encapsulated in the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps developed by the World Health Organisation in 1980:

In 1997, the World Health Organisation updated the 1980 model, replacing the terms ‘disability’ with ‘activities’ and ‘handicap’ with ‘participation’.

The philanthropic model of disability

The philanthropic model of disability informs much of the work undertaken on behalf of disabled people by voluntary and charitable organisations. It has been most critically and comprehensively described in an analysis of representations of disabled people in charity advertising (Hevey 1992). Through the use of particular forms of visual and verbal imagery, disabled people have been variously represented in charity advertisements as tragic, brave objects of pity, or as heroically overcoming their impairments. Either way, it is suggested that they are dependent upon charitable support, and grateful for it.

The philanthropic model has a profound influence upon media accounts of disability, as a glance through any tabloid or local newspaper will confirm. However, alternative images of disabled people are starting to emerge. For example, recent fashion initiatives display, celebrate and play upon motor and sensory impairments and effectively reconfigure disabled people as sexualised, image-conscious consumers (as described in a feature in the September 1998 issue of Dazed and Confused).

Disability theorists are starting to deconstruct the pity and fear with which disabled people have traditionally been regarded, and to explore these stigmatising reactions within the context of cultural and economic factors. Analysis of cultural stigma explores, among other things, the relationship between economic productivity and able-bodiment. This relationship was transformed with industrialisation – a process that rendered people with physical impairments effectively non-productive and economically worthless (Barnes, 1996). A concept such as this seems relevant to aphasia as, in the late 1990s, fast, effective, multi-channel communication has become an essential feature and component of productivity. ‘Communication skills’ feature in every work appraisal and school report. This may offer some explanation for the fact that people with aphasia, whose communication skills are compromised, describe a sense of being stigmatised and culturally sanctioned.

The social model of disability

The social model of disability emerged within British disability theory and offers an alternative construction to dominant medical and philanthropic philosophies. The social model challenges the medical model by reconfiguring disability in terms of social oppression and by questioning the function and nature of rehabilitation itself. According to this model, disability does not inevitably stem from the functional limitations of impaired individuals, but from the failure of the social and physical environment to take account of their needs. It is ‘a political issue, a matter of civil rights, not medical needs’ (Abberley, 1991, p174). While the social model definition of impairment remains largely the same, the concept of ‘handicap’ disappears, and disability is reconceptualised:

Disability is the loss or limitation of opportunities that prevents people who have impairments from taking part in the normal life of the community on an equal level with others due to physical and social barriers. (Finkelstein & French, 1993, p28)

Like other models of disability, the social model is intrinsically complex and constantly evolving. It draws on many influences, particularly anti-sexist and anti-racist movements. However, it can be fairly succinctly described in terms of two key concepts: disabling barriers and the disabled identity.

Disabling barriers

According to the social model, people are disabled, not by their own inabilities but by the socially constructed barriers which spring up around them. These can take a variety of forms:

All disabled people experience disability as a social restriction, whether the...