- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to Environmental Remote Sensing

About this book

Taking a detailed, non-mathematical approach to the principles on which remote sensing is based, this book progresses from the physical principles to the application of remote sensing.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Remote Sensing Principles

1 Monitoring the Environment

1.1 Growth in Awareness of Environmental Problems

As we enter the twenty-first century, most people are aware of environmental problems and are concerned about the quality of life they can enjoy in their own locality. These feelings are triggered mainly by events affecting the air they breathe, the water they drink, or the open green spaces they are accustomed to using for leisure. In the main the problems arise from human use of land, air and water, for pressures on land and resources are higher than ever before, and growing fast.

Some people live in constant fear of hazardous environmental conditions, which can lead with frightening speed to disasters that threaten life and property. These environmental threats may involve earthquakes, volcanic activity, flooding, storms, droughts or other factors. Each of these may be of sufficient severity to cause considerable damage to property and loss of human life.

As people become more mobile and see beyond their immediate localities they grow increasingly aware of even larger-scale problems facing particular regions of the global environment. The Earth is the only planet in the universe known to sustain humanoid life. Yet it is human activity that is now conspiring to reduce the life-supporting capacity of planet Earth. In part this is due to the disproportionate consumption of world resources by an affluent minority, and in part to the damage caused by high-tech systems and attendant ways of life. Meanwhile, a majority of the world's population is relatively poor and struggling to achieve better standards of living, including an adequate supply of food. And there is growing evidence that many nations are degrading or even destroying globally significant resources in their own struggle for betterment.

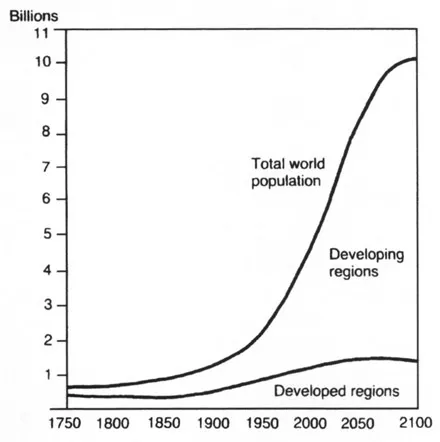

Clearly we as a species have developed the capability of subjugating all other biological species to our own ends. One spectacular result is that the human population of the Earth has grown from about 200 million some 2000 years ago to about 5 billion today. It is still rising today (Fig. 1.1), and population pressures are expected to continue to build in the new century. Therefore, the very important question arises as to when the global population may stabilize. Some authorities have suggested this may not happen until figures of between 10 and 14 billion have been reached.

Through activities resulting from this population explosion we are decimating the biological and genetic diversity of the Earth. An estimated 25 000 plant species and more than 1000 vertebrate species surviving today are now threatened with extinction. Because of these trends, there is justifiable concern that our relationship with the biosphere (the thin covering of the planet that contains and sustains life) will continue to deteriorate, and at an accelerating rate, unless a new environmental ethic is adopted.

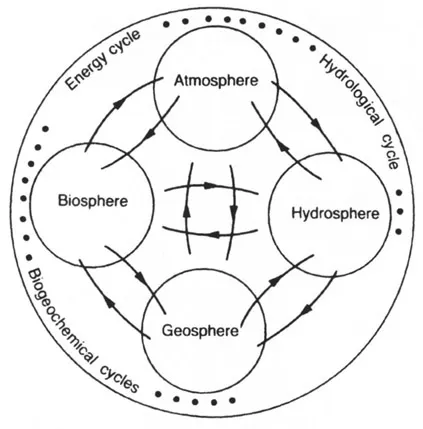

Moreover, although the human race and other living creatures inhabit the biosphere, the global environmental system contains other important components that interact with it (Fig. 1.2). These include the atmosphere, geosphere and hydrosphere, each of which makes

Fig. 1.1 World population growth with future projections.

important contributions to the conditions of the environment affecting human life. The principal processes influencing the development of the global environment drive the energy, hydrological and biogeochemical cycles which affect us all.

Although it is often hard to dissect out the relationships linking us with our environment that are distinctly natural, technical or cultural, there is no doubt that, through our ability (conscious or unconscious) to interfere with natural phenomena, our species is today a key, possibly the key, participant in planetary processes. Many chains of cause and effect are intricately ramified, and inadequately known or understood. The great majority involve so-called feedback effects. Thus even our 'improvements' to the environment may prompt another person's environmental problems —or, ultimately even our own.

Fortunately, alongside a recent growth in environmental concern there has also been a growth in our awareness of the need for conservation. Conservation, like 'development', is designed to be beneficial primarily to people. However, whereas development aims to

Fig. 1.2 Components of the global environmental system. (Courtesy, NASA.)

achieve benefits through exploitation of the environment, conservation aims to achieve benefits by ensuring that such use is 'sustainable'. There is a growing realization that the world economy must be based on sustainable development, not the destruction of natural resources. In this respect, living resource conservation has three specific objectives:

- To maintain essential ecological processes and life-support systems.

- To preserve genetic diversity.

- To ensure the sustainable utilization of species and ecosystems.

Many organizations, activities and reports relating to our environment and its everyday use have been evident since the first World Environment Day in 1974. The International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU) has been a major coordinator of international environmental research programmes. Likewise, initiatives of the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) have played important parts in developing knowledge of environmental problems and how to solve them. Programmes such as the International Geophysical Year (1957-1958) and the International Biological Programme (IBP) running from 1964 to 1974 were early studies of significance. The UNEP has been active in promoting the Global Environment Monitoring System (GEMS), which provides databases for the international community on environmental matters. In more recent years the practical lead in developing an integrated concept of research on the global environment has come from the USA. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) have made significant contributions to this. One result is the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP), supported by the ICSU. Other large-scale studies of special note are the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) inaugurated in 1979, and the much younger Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), confirmed in 1991.

The IGBP is just one of many major projects that are attempting to integrate a wide variety of disciplines and areas of study within global environmental research programmes. In it, particular emphasis is being placed on the need for development of an adequate global data and information system. Without this it will be impossible to make sound policy decisions for the maintenance of a stable and productive Earth environment. In assessing environmental matters, it has become commonplace to follow a well-established sequence of steps. These include:

- The recognition of forms, structures, and/or processes of significance.

- The identification of such phenomena in their real world situation(s).

- The recording of their distributions, often through both space and time.

- The assessment of these distributions, sometimes singly, but more often in some combinations.

- Attempts to understand the nature and causes of any specially significant relationships between and amongst the key phenomena and processes.

It is only when such background studies have been completed successfully that their results can be used to benefit the human race and its environment. Commonly these results are used in one or more of the following ways:

- The preparation and execution of schemes of environmental or resource management.

- The prediction of forthcoming events, especially those over which we have less direct control.

- The planning and development of future projects to modify and improve the environment.

At the heart of the all-important basic — or background — studies are problems concerned with observation, for it is only when we know the true state of our environment that we can predict the future with confidence, including effects of our own impacts on it. Data must be obtained by appropriate means; they must be put into permanent forms; and there are great advantages if they lend themselves readily to computer processing for rapid analysis, interpretation and intercomparison. It is here that environmental remote sensing has its most important part to play, and it is with such activities that this book is mainly concerned. By common consent, remote sensing is beginning to fulfil a long-recognized need for both intensive and extensive monitoring of the Earth, simultaneously in much more detail yet also with much greater uniformity than has ever been possible before.

But first, let us review the development and roles of environmental observation by longer-established means, which will help to set the scene.

1.2 In Situ Sensing of the Environment

Humans have made measurements of key aspects of our environment since an early stage in the development of our civilization and culture. Examples of primitive measuring devices include the famous Nilometer by which water levels in the River Nile were noted, and the rudimentary rain gauges used by natural philosophers in the city states of Ancient Greece. The European Renaissance of art, science and literature marked a very significant surge of interest in the need for, and design of, monitoring instruments. Attention began to be paid not only to environmental variables or effects which were readily visible, but also to others less directly evident in the world of nature. In the present context the invention of the thermometer by Galileo at the end of the seventeenth century is particularly noteworthy. A steady deepening of interest in environmental factors and conditions ensued in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The scientific rebirth of the Renaissance period and its aftermath was followed by a rapid acceleration in our concern for the environment as the twentieth century unfolded. Not only could the environment be monitored by a wide range of sophis...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- The authors

- Abbreviations and acronyms

- PART ONE REMOTE SENSING PRINCIPLES

- PART TWO REMOTE SENSING APPLICATIONS

- Appendix: Internet sources of further information

- Selected bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Introduction to Environmental Remote Sensing by Eric C. Barrett,Leonard F. Curtis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.