eBook - ePub

Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

A Handbook

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides a complete and fundamental overview, from a psychoanalytical point of view, on theoretical and clinical aspects of psychodynamic or psychoanalytic psychotherapy. It includes the theory of the human mind, psychic development, psychic conflicts, trauma, and dreams.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

PSYCHOANALYTIC THEORY OF THE HUMAN MIND

Psychoanalytic models of the mind

What is psychodynamic psychotherapy; what does the term “psychodynamic” mean? For an answer to this question, let us look at the origins of psychodynamic science, rooted in psychoanalysis and developed by Freud from 1893 onwards. Psychiatric diagnosis in Freud’s time was no more than classifying people into different diagnostic categories, for instance, the so-called “psychopathic personalities” with hysteric, perverse, criminal, or addictive traits, the psychoses (schizophrenia, manic–depressive illness), neurasthenia, etc. Today, our diagnostic systems in psychiatry are much more refined, operationalised, and validated than they were at the turn of the twentieth century: we have ICD-10 or DSM-IV guide us. Nevertheless, the content of these diagnostic systems, too, is restricted to descriptive symptom diagnoses and does not tell us anything about the psychodynamics of the patient’s psychic disease. Therefore, for our psychotherapeutic purposes, the symptom diagnosis has to be supplemented by a psychodynamic diagnosis (see “Operationalised psychodynamic diagnosis” in Chapter Seven).

Psychiatric therapy in Freud’s time was mainly somatic treatment, operating on the body through hospitalisation, psychopharmacological medication (e.g., sedatives and stimulants—Freud also experimented with cocaine), electrotherapy, etc. However, for neurotic disorders these somatic therapy forms proved ineffective. Freud found out that in order to help these patients, it was not enough to explore their symptoms, formulate a descriptive symptom diagnosis, and prescribe some somatic treatment. What these patients needed was a therapist who would explore why patients became ill and developed their symptoms at a particular moment or in a specific situation of their life; the reason for their becoming ill (the function and the meaning of their symptoms); in other words, try to understand understand the patient’s symptoms as an expression of some inner “power struggle” between conflicting forces, especially emotional conflicts between specific wishes, needs, and fears of the patient.

Freud discovered that often the deepest longings and fears are unknown to the patient himself (they are unconscious), so you cannot simply ask the patient and get an answer. The therapist must, rather, learn the non-verbal, symbolic, and highly emotional “language of the unconscious mind”, which is expressed not in words but in the patient’s behaviour, his relationships towards other people, his emotional signals, phantasies, and dreams. By understanding not only words but also these non-verbal expressions of the patient’s deepest motives and hidden emotions, we can help the patient to better understand himself and others and to master his problems without becoming ill as a result of them.

This approach—not just exploring symptoms as such, but wanting to understand their function and meaning in terms of the underlying emotional forces—is Freud’s most important discovery, and this is what he called the psychodynamic point of view. The old Greek word dynamis means power, or force. Of course, here we are dealing not with physical forces, but psychological forces, which we describe in terms of

● drives (e.g., the sexual drive, aggressive impulses of competition or revenge);

● needs (the need for safety, for closeness, for affirmation and self-assertion, for autonomy and independence, the need to feel great sometimes, the need to have someone you can admire and take as a model, etc.);

● emotions (love and hate, anxiety and fear, shame, guilt, envy, jealousy, pride, arrogance, admiration, contempt, etc.).

What Freud and later psychoanalysts discovered is that often

● these manifold dynamic forces are not in harmony but in conflict with each other;

● one important reason for conflict is that some of the deepest needs, emotions, and impulses are rather immature, persisting from childhood and in conflict with adult self-concepts and values; in short, with the adult part of the patient’s personality;

● our patients’ deepest emotional conflicts, which made them become ill, are often unknown to them because these are mostly unconscious;

● such unconscious conflicts are often expressed indirectly, non-verbally, in the patient’s symptoms, interpersonal relations, emotional and behavioural signals, which we must understand in order to help the patient in therapy;

● in clinical practice, symptom diagnosis alone is mostly insufficient and has to be supplemented by a psychodynamic diagnosis in terms of emotional conflicts and the way a patient deals with them (defence mechanisms), developmental deficits, personality structure, etc.;

● psychoanalytical psychotherapy aims to help the patient to better understand and accept himself, to realise his emotional conflicts and to develop more adequate solutions for them. Since many of our patients have been hampered in their personality development, resulting in developmental deficits, an additional aim of psychodynamic psychotherapy should be to help them to face reality and resume their personality development in those areas where they are still clinging to childish or juvenile forms of behaviour and experience—in other words, help them to grow up to be a mature adult person.

On the basis of his clinical observations, Freud tried to order his findings systematically and develop a psychological model of mental functioning. Since the neuro-scientific knowledge of the brain and its functions was still very limited in his time, Freud had to give up his first attempt, in 1895, at constructing a neuropsychological model of mental functioning in health and mental disease. So, from that time on, he tried to outline a psychological theory of mental functioning. I want to be brief and concentrate upon the essentials.

In the development of psychoanalysis, we may distinguish first Freud’s three models of the mind. After Freud’s death in 1939, the development did not stop, but as the clinical spectrum changed, psychotherapists were confronted with new kinds of patients (for instance, patients with narcissistic and borderline personality disorder), necessitating new psychodynamic models to understand and treat them. From our clinical practice today, we see that the earlier models were not completely wrong and they still have their value, albeit limited, but they had to be supplemented by new models as soon as new kinds of patients appeared whose mental disorder could not be explained by way of the old model. So, all these models have to do with the kind of patients whom psychoanalytic therapists had to treat.

The first model—the model of “blocked affect—therapeutic abreaction”—was developed by Freud and his colleague Breuer when they treated hysterical patients with dissociative symptoms and found that many of these patients suffered from some early trauma, such as sexual abuse, early loss of a beloved parent, etc. In the beginning, Freud used hypnosis in order to facilitate remembering, later (in the 1890s) he replaced this with the technique of free association—psychoanalysis. In the course of treatment, when the patients remembered the trauma that had been repressed, they often enacted the traumatic event in dramatic form in the therapy situation, and afterwards, they often felt much better or even lost their symptoms.

The second topographic model was suitable for a wider spectrum of neurotic disorders: anxiety hysteria and phobic neurosis, conversion hysteria, and obsessive–compulsive disorder.

The third, structural model had to be developed to account not only for the symptom neuroses, but also for depression, and narcissistic, masochistic self-defeating, and paranoid personality disorders.

Later models of the mind developed after Freud’s death (e.g., object relations theory, self psychology) are still more apt to account for the less integrated forms of severe personality disorders, for example, borderline, narcissistic, schizoid, and antisocial personalities.

Freud’s first model to explain what he observed in his—mostly female—hysterical patients was a model of blocked affect and therapeutic abreaction. We find a good description, together with very vivid case presentations, in his book (with Breuer) Studies on Hysteria, published in 1895. Using hypnosis, or his early forced association method, Freud often found that at the centre of the patient’s suffering there was some repressed memory (of sexual abuse, for example, or early loss of a beloved parent), or some secret passion, forbidden love, or hidden death wish against a close relative, etc. When therapy succeeded in recovering this personal secret, thus helping the patient to remember and admit what had happened and to re-experience vividly in the therapy situation the traumatic event, together with the painful emotions associated with it, the neurotic symptoms (such as hysterical paralysis, functional pain, anxiety attacks) disappeared—at least for some time. So, Freud (1895d, p. 7) discovered “Hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences”. The typical sequence of events, according to this model, is as follows.

1. The patient had been overwhelmed by her emotions in connection with a psychic trauma or unbearable passionate experience (secret passion, forbidden love, or hidden death wish against a close relative, etc.).

2. The traumatic experience was repressed from consciousness, because it was too painful, so it could not be remembered (amnesia for the trauma). The traumatic affects (death anxiety, excitement, helpless rage, shame, and guilt) were blocked from feeling and “converted” (conversion) into functional somatic symptoms—so-called neurotic (hysterical) symptoms.

3. In therapy, the patient feels safe enough to lift the “repression barrier” and re-experience the traumatic events, together with the painful affects, because, under the protection of therapy, the traumatic affects are no longer blocked, but can be expressed, that is, “abreacted”. By way of abreaction of the formerly blocked affect, the patient is relieved from pressure and the symptoms are dissolved.

Limitations of this model are: relief from symptoms usually was only temporary; often the symptoms reappeared later (no working through); psychodynamic understanding was limited; there was insufficient appreciation of inner conflict.

The unconscious (topographic model, 1900)

Freud’s first model of the mind was a model of the traumatised psyche, a model of the post trauma mind. When Freud realised that at least some of the traumatic events which he reconstructed from the fantasies, dreams, and associations of his hysterical patients probably had never really happened, but had been a fantasy construction of the patients, he arrived at a crisis. In the end, he recognised that on the unconscious level, our minds are not able to distinguish between fantasy and reality, so, in the unconscious mind, fantasy is treated as if it were real—not factual reality, but psychic reality. This finding was very important. Freud had discovered the enormous psychodynamic role of unconscious wishful fantasies and of negative unconscious convictions. For example, Anna O, the famous female hysterical patient of Freud’s colleague Breuer, towards the end of her treatment with Breuer, developed the unconscious wishful fantasy that she was pregnant by her therapist, so that he would leave his wife and live with her. Although this was not real, the patient behaved as if it were real. What she presented was a false pregnancy, but with the typical appearance of a real pregnancy.

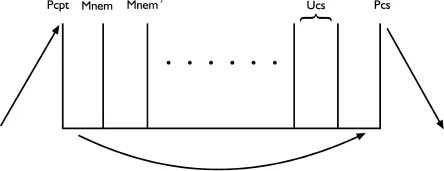

In the seventh chapter of his book The Interpretation of Dreams (1900a) Freud described his new topographic model of the mind. According to this model, the mind is an organ (a “psychic apparatus”, as he called it) for the processing of stimuli—perceptual information from outside, drive impulses and emotions from inside. These stimuli are stored in memory systems, that is, associative networks of emotionally charged ideas. Parts of these memories are preconscious, which means they are accessible to consciousness, which is kind of an inner sense organ. Other memories or ideas are unconscious: they are kept out of consciousness by repression or some other defence mechanism, because awareness of these memories or wishful fantasies would cause painful feelings of fear, or shame, or guilt. So, Freud’s new model was like a topography of the human mind, with an unconscious, a preconscious, and a conscious area (Figure 1.1).

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the Editors and Contributors

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Preface

- Chapter One Psychoanalytic Theory of the Human Mind

- Chapter Two Psychoanalytic Theory of Psychic Development Through the Life Span

- Chapter Three Conflict, Trauma, Defence Mechanisms, and Symptom Formation

- Chapter Four Dreams

- Chapter Five The Therapeutic Relationship

- Chapter Six The Setting in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

- Chapter Seven Diagnosis and Treatment in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

- Chapter Eight Psychopathology and Psychodynamics of Neurosis

- Chapter Nine Psychopathology and Psychodynamics of Psychosomatic Disorders

- Chapter Ten Psychotic Disorders, Addiction, and Suicide

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy by Matthias Elzer, Alf Gerlach, Matthias Elzer,Alf Gerlach in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.