![]()

PRE-ROMAN POMPEII

AND HERCULANEUM

The vast majority of our evidence for the early history of Pompeii and Herculaneum is archaeological. Scatterings of prehistoric artefacts indicate a long history of activity on the lava plateau at the mouth of the River Sarno occupied by the later town of Pompeii, but we have to wait until the sixth century BC for what can be identified as a city to develop on the site. During that century, the Doric Temple and sanctuary of Apollo were constructed, and an area of around 66 hectares was enclosed in a defensive wall. It had long been thought that it was possible to discern in the current street pattern the less regular layout of the earliest settlement at Pompeii. This so-called ‘Altstadt’, or ‘Old Town’, covered an area of about 14 hectares. It is now clear, however, that this area was not an original nucleus from which the settlement later expanded. Exactly what it does represent is still much debated. Ten miles away from Pompeii around the Bay of Naples, Herculaneum was a much later foundation, with the earliest evidence on that site dating only from the fourth century BC, and was on a much smaller scale of approximately 20 hectares. Nevertheless, both towns celebrated their mythological foundations by the Greek hero Hercules (A3–6).

The earliest writing from Pompeii is scratched upon fragments of pottery, notably in a deposit of votive offerings in the Temple of Apollo. Some of these texts are dedications, while others record the identity of the owner of the pottery. They range in date from c. 600 to c. 475 BC and are written in Etruscan. Otherwise, the earliest decipherable writing from the site (second/first centuries BC) appears in Oscan, an Italic language used in parts of southern Italy. Written from right to left, it uses an alphabet different from that of Latin, although some words mirror Latin usage. Monumental inscriptions and graffiti in Oscan provide our main documentary source for life in Pompeii before it came directly under Rome's control in the first century BC (A11–17, A20–21, A27–30). These Oscan inscriptions give an insight into how the town was administered and what gods were worshipped. Although a few of these inscriptions were still on public display in AD 79, the majority were found where they had been reused as building material. By contrast, only one monumental Oscan inscription has been found so far at Herculaneum (A18), with only two other Oscan texts also known, a graffito in the Samnite House (Ins. V.1), recording possibly craftsmen's signatures, and another on a tile.

Two main areas of pre-Roman burials have been uncovered at Pompeii. Twenty-nine inhumations from the fourth to mid-second centuries BC were found beyond the Herculaneum Gate, in the area to the west of the last shops along the north side of the street and in the area of the Villa of the Mosaic Columns. These were not monumental tombs, and contained few grave goods, including pottery, coins and a bronze mirror. The Fondo Azzolini necropolis, about 500 metres beyond the Stabian Gate, contains an area (c.400 square metres) enclosed by a wall, where 44 inhumations from the fourth to second centuries BC were discovered. Almost all the pre-Roman tombs are non-monumental, with only one (Tomb X) containing two small burial chambers preceded by a vestibule. Among the few grave goods were some coins minted at Naples, metal strigils (used by bathers to clean their skin), bronze bracelets and silver earrings. There were also 119 Roman-period cremations, and inscriptions from these identify the deceased as members of the Epidii family. This raises the possibility of a continuous sequence of burials by that family from the Samnite period down into Roman times. A picture of another prominent local family, the Popidii, can be pieced together from a variety of different sources (A27–31).

During the third century BC, Pompeii entered into alliance with Rome, a period that heralded major developments in the town's public buildings, infrastructure, and domestic spaces. By the late second century BC we can see the impact of Hellenistic culture upon Pompeii's public and private buildings (A19–25). By contrast, Herculaneum's main phase of urban development appears to have occurred only later, towards the end of the first century BC. The monumentalization of the Sanctuary of Dionysus just outside Pompeii in the late third/early second century BC (A19–21) and construction of the Basilica at its heart in the late second century BC illustrate the impact of Hellenistic culture upon the town's public character. The long-established Sanctuary of Apollo adjacent to the Forum was also re modelled along Hellenistic lines in the second century BC, when a temple in stone replaced the wooden temple. The addition of a palaestra and portico to the Stabian Baths in the mid-second century BC also reflected the same tendency. At about the same time, the town's elite increasingly adopted Hellenistic culture in their private lives too, and the House of the Faun provides an outstanding example of this (A22–23). The impact of the Greek language is evident in the names of Oscan measures inscribed (and later erased) upon the Forum's measuring table, which were derived from Greek (H98).

* * *

GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION OF POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM (A1–2)

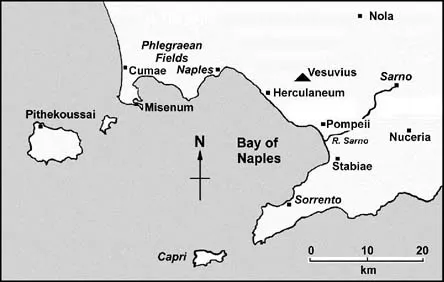

A1 Map of the Bay of Naples

Figure 1.1 Map of the Bay of Naples (modern place names given in italics)

A2 A description of the Bay of Naples

From here Italy curves towards the Tyrrhenian Sea and the other side of the land … the bay of Pozzuoli, Sorrento, Herculaneum, the sight of Mount Vesuvius, Pompeii, Naples, Pozzuoli, Lake Lucrinus, Lake Avernus, Baiae, Misenum – that being now the name of the place of the former Trojan soldier – Cumae, Liternum, the River Volturnus, the town Volturnum, the pleasant shores of Campania.

(Pomponius Mela, Geography 2.4.70)

Pomponius Mela probably wrote his geography in celebration of Claudius' conquest of Britain in AD 43.

ORIGINS AND EARLY HISTORY OF POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM (A3–10)

MYTHOLOGICAL FOUNDATION OF POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM BY HERCULES (A3–6)

As one of his twelve labours, Hercules was sent to the western edge of the world, to Gades (modern Cadiz, Spain). Having defeated the monster Geryon there, he drove Geryon's herd of cattle back to Greece, passing through Italy on his travels. As he did so, he was said to have bestowed upon Pompeii its name, derived from the word for procession common to Greek and Latin (pompe/ pompa). Nearby Herculaneum was also reputedly founded by the Greek hero and named after him. The cult of Hercules was one of the earliest known at Pompeii, where he was worshipped along with Athena in the Doric Temple. Both deities are represented on fourth-century BC terracotta antefixes from the so-called ‘Triangular Forum’ (actually a sanctuary), whose Doric Temple may have honoured him alongside Athena (Carafa 2011: 95, Figure 5). At Herculaneum, the hero featured in sizeable wall paintings found in various public buildings: two paintings – one depicting his introduction among the gods on Mount Olympus, and the other his contest with the river-god Achelous – filled both sides of the shrine in the ‘College of the Augustales’, while another in a grandiose building on the other side of the decumanus (‘so-called basilica’) illustrated Hercules' discovery of the infant Telephus (MANN inv. 9008). A frieze of episodes in the life of Hercules was also found in the same building.

A3 An etymological explanation of Pompeii's name

Pompeii (was founded) in Campania by Hercules, who had led a procession {pompa} of cattle from Spain as victor.

(Isidore, Etymologies 15.1.51)

Isidore, a late antique Christian writer (sixth/seventh centuries AD) from Spain, wrote a massive encyclopaedia.

A4 Hercules’ pompa

As he was c...