eBook - ePub

Relational Patterns, Therapeutic Presence

Concepts and Practice of Integrative Psychotherapy

This is a test

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Relational Patterns, Therapeutic Presence

Concepts and Practice of Integrative Psychotherapy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book presents a comprehensive integrative theory and style of therapeutic involvement that reflects a relational and non-pathological perspective. It discusses various psychotherapy theories and methods, and examines the implications and magnitude of an involved therapeutic-relationship.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Relational Patterns, Therapeutic Presence by Richard G. Erskine in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Integrative psychotherapy: theory, process, and relationship

Just as relationships between people are dynamic processes, so is the development of theory, originating as it does from the dynamic process of the individual theorist(s) and from the dynamic process of each therapeutic relationship which guides and informs that theory. Thus I would like to take the opportunity in this opening chapter to talk about how a relationally focused integrative psychotherapy has developed and how I think about it and practice it today.

The term “integrative” of integrative psychotherapy has a number of meanings. The original and primary meaning of “integrative psychotherapy” refers to the process of integrating the personality: helping the client to assimilate and harmonize the contents of his or her ego states, relax the defense mechanisms, relinquish the life script, and reengage the world with full contact. It is the process of making whole: taking disowned, unaware, unresolved aspects of the ego and making them part of a cohesive self. Through integration, it becomes possible for people to have the courage to face each moment openly and freshly, without the protection of a preformed opinion, position, attitude, or expectation.

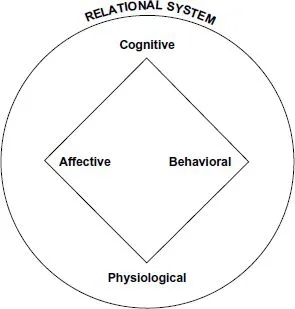

“Integrative” also refers to the integration of theory, the bringing together of affective, cognitive, behavioral, physiological, and systems approaches to psychotherapy. The concepts are utilized within a perspective of human development in which each phase of life presents heightened developmental tasks, need sensitivities, crises, and opportunities for new learning. Integrative psychotherapy takes into account many views of human functioning: psychodynamic, client centered, behaviorist, family therapy, Gestalt therapy, neo-Reichian, object relations theories, psychoanalytic self psychology, and transactional analysis. Each provides a valid explanation of behavior, and each is enhanced when selectively integrated with the others. The psychotherapeutic interventions are based on research-validated knowledge of normal developmental process and the theories describing the self-protective defensive processes used when there are interruptions in normal development.

The ABC’s and P

I presented the preliminary ideas of integrative psychotherapy in a series of lectures at the University of Illinois in 1972. A brief outline of these ideas was published in 1975 and then elaborated upon in 1980. Many of the ideas that my colleagues and I have written about have emerged from the case presentations, research, and discussions in the Professional Development Seminars of the Institute for Integrative Psychotherapy. I have an immense gratitude to this group of knowledgeable and curious psychotherapists who have helped me develop and refine the theories and methods of a relationally oriented integrative psychotherapy. Some of the clinical methods that will be briefly described in this and the following chapters are presented transaction-by-transaction in Integrative Psychotherapy in Action (Erskine & Moursund, 1988). In three subsequent books we elaborated on both the theory and methods of integrative psychotherapy. The books are: 1) Beyond Empathy: A Therapy of Contact-in-Relationship (Erskine, Moursund, & Trautmann, 1999); 2) Integrative Psychotherapy: The Art and Science of Relationship (Moursund & Erskine, 2004); and 3) Theories and Methods of an Integrative Transactional Analysis (Erskine, 1997c).

Our focus of integration is on five primary dimensions of human functioning and therefore our psychotherapeutic focus: cognitive, behavioral, affective, and physiological; each within a relational system. Simply put, the cognitive theories stress the mental processes of a person and focus on the question, “Why?” The cognitive approach explains and provides a model of understanding. Why do we have the problems that we have? Why does our mind work the way it does? It assumes that psychotherapy is an intellectual process and when the client comes to understand why he or she behaves and thinks in a particular manner, he or she will solve the conflicts involved.

Significantly different from the cognitive is the behavioral approach which deals with the question of “What?” Behavioral therapy describes what exists and attempts to shape appropriate behavior. What is the specific problem? What contingencies shaped and now maintain the behavior? What changes are necessary in the reward system to produce new behavior? And since behavioral therapy emerged out of experimental psychology, there is a great deal of attention given to what measures are to be applied to evaluate the changes made. The application of behavioral therapy involves a shift away from the question of “Why?” and instead is focused on “What?” The goal of behavioral therapy is to identify and reinforce desired behaviors.

Both cognitive and behavioral therapy are significantly different from an affective psychotherapy. An affective approach deals with the question “How?” How does a person feel? Here the focus is on the internal experiential process: how each person phenomenologically experiences what has happened. The major focus is not on the why of cognitive therapy or the what of behavioral therapy, but on how we emotionally experience ourselves in the here and now. A basic premise in affective therapy is that people are out of touch with their feelings and internal processes. It is assumed that removing blocks to emotions and fully expressing repressed affect will produce an emotional closure and provide for a fuller range of affective experiences.

In addition to the dimensions of affect, behavior, and cognition, we include the physiological dimension. As many of the mind/body theories and modalities have developed, including the research on psychoneuroimmunology, it became imperative to include a focus on the body as an integral aspect of psychotherapy. Disturbances in affect or cognition can adversely affect the body as physiological dysfunction can impact changes in behavior, affect, and cognition.

The affective, behavioral, cognitive, and physiological foundations of the human organism are viewed from a systems perspective—a cybernetic model wherein any dimension has an interrelated effect on the other dimensions. Just as the individual is affected by others in a family or work system, he in turn contributes to the uniqueness of the system. In a similar systemic way the intrapsychic and observable dimensions of an individual are inherently influenced in the psychological function of the individual. The systems perspective leads to the question, “What is the function of a particular behavior, affect, belief, or body gesture on the human organism as a whole?” A major focus of an integrative psychotherapy is on assessing whether each of these domains—affective, behavioral, cognitive, and physiological—are open or closed to contact and in the application of methods that enhance full contact.

Contact

A major premise of integrative psychotherapy is that contact constitutes the primary motivating experience of human behavior. Contact is simultaneously internal and external: it involves the full awareness of sensations, feelings, needs, sensorimotor activity, thought, and memories that occur within the individual, and a shift to full awareness of external events as registered by each of the sensory organs. With full internal and external contact, experiences are continually integrated. To the degree that the individual is involved in full contact needs will arise, be experienced, and be acted upon in relation to the environment in a way that is organically healthy. When a need arises, is met, and is let go, the person moves on to the next experience. When contact is disrupted, however, needs are not met. If the experience of need arousal is not closed naturally, it must find an artificial closure. These artificial closures are the substance of physiological survival reactions and script decisions that may become fixated. They are evident in the disavowal of affect, habitual behavior patterns, neurological inhibitions within the body, and the beliefs that limit spontaneity and flexibility in problem solving and relating to people. Each defensive interruption to contact impedes full awareness. It is the fixation of interruptions in contact, internally and externally, that is the concern of integrative psychotherapy.

Relationships

Contact also refers to the quality of the transactions between two people: the full awareness of both one’s self and the other, a sensitive meeting of the other and an authentic acknowledgement of one’s self. Relationships between people are built on contact. Both internal and interpersonal contact are necessary for establishing and maintaining relationships. Integrative psychotherapy makes use of many perspectives on human functioning. For a theory to be integrative it must also separate out those concepts and ideas that are not theoretically consistent in order to form a cohesive core of constructs that inform and guide the psychotherapeutic process.

The single most consistent concept in the psychology and psychotherapy literature is that of relationship. From the inception of a theory of contact by Laura and Frederick Perls (Perls, 1944; Perls, Hefferline, & Goodman, 1951) to Fairbairn’s (1952) premise that people are relationship-seeking from the beginning and throughout life, to Sullivan’s (1953) emphasis on interpersonal contact, to Guntrip’s (1971) and Winnicott’s (1965) relationship theories and corresponding clinical applications, to Berne’s (1961, 1972) theories of ego states and script, to Rogers’s (1951) focus on client-centered therapy, to Kohut (1971, 1977) and his followers’ (Stolorow, Brandschaft, & Atwood, 1987) application of “sustained empathic inquiry,” (p. 10) to the feminist and relationship theories developed by the Stone Center (Bergman, 1991; Miller, 1986; Surrey, 1985), there has been a succession of teachers, writers, and therapists who have emphasized that relationship—both in the early stages of life as well as throughout adulthood—are the source of that which gives meaning and validation to the self.

The literature on human development also leads to the premise that the sense of self and self-esteem emerge out of contact-in-relationship. Erikson’s (1950) stages of human development over the entire life cycle describe the formation of identity (ego) as an outgrowth of interpersonal relations (trust vs. mistrust, autonomy vs. shame and doubt, etc.). Mahler’s (Mahler, 1968; Mahler, Pine, & Bergman, 1975) descriptions of the stages of early child development place importance on the relationship between mother and infant. Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980) has emphasized the significance of early as well as prolonged physical bonding in the creation of a visceral core from which all experiences of self and other emerge. When such contact does not occur in accordance with the child’s needs there is a physiological defense against the loss of contact, poignantly described by Fraiberg in “Pathological Defenses in Infancy” (1982).

From a theoretical foundation of contact-in-relationship coupled with Berne’s concept of ego states (particularly Child ego state) comes a natural focus on child development. The works of Daniel Stern (1985) and John Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980) are presently most influential, largely because of their emphasis on early attachment and the natural, lifelong need for relationship. Based on his research of infants, Stern delineates a system for understanding the development of the sense of self which emerges out of four domains of relatedness: emergent relatedness, core relatedness, intersubjective relatedness, and verbal relatedness. As we take this view of the developing person into our psychotherapy practice, we have a deep appreciation for the vitality and active constructing that is so much a part of who our client is. By looking at the client from a simultaneous perspective of what a child needs and how he or she processes experiences as well as these being ongoing life processes, we use our self in a directed way to assist the process of developing and integrating.

What is frequently very significant in the psychotherapy is the process of attunement, not just to discrete thoughts, feelings, behaviors, or physical sensations, but also to what Stern terms “vitality affects,” such that we try to create an experience of unbroken feeling-connectedness. The sense of self and the sense of relatedness that develop seem crucial to the process of healing, particularly when there have been specific traumas in the client’s life, and to the process of integration and wholeness when aspects of the self have been disavowed or denied because of the failures of contact-in-relationship.

Psychological constructs

Integrative psychotherapy correlates constructs from many different theoretical schools resulting in a unique organization of theoretical ideas and corresponding methods of clinical intervention. The concepts of contact-in-relationship, ego states, and life script are central to our integrative theory.

Ego states and transference

Eric Berne’s (1961) original concept of ego states provides an overall construct that unifies many theoretical ideas (Erskine, 1987, 1988). Berne defined the Child ego states as an archaic ego consisting of fixations of earlier developmental stages; as “relics of the individual’s own childhood” (1961, p. 77). The Child ego states are the entire personality of the person as he or she was in a previous developmental period (Berne, 1961, 1964). When functioning in a Child ego state the person perceives the internal needs and sensations and the external world as he or she did in a previous developmental age. This includes the needs, desires, urges, and sensations; the defense mechanisms; and the thought processes, perceptions, feelings, and behaviors of the developmental phase when fixation occurred. The Child ego state fixations occurred when critical childhood needs for contact were repeatedly not met and the child’s use of defenses against the discomfort of the unmet needs became habitual.

The Parent ego states are the manifestations of introjections of the personalities of actual people as perceived by the child at the time of introjection (Loria, 1988). Introjection is a self-stabilizing defense mechanism (including disavowal, denial, and repression) frequently used when there is a lack of full psychological contact between a child and the adults responsible for his or her psychological needs. By internalizing the parent with whom there is conflict, the conflict is made part of the self and experienced internally, rather than with that much-needed parent. The function of introjection is in providing the illusion of maintaining relationship, but at the expense of a loss of self.

Parent ego state contents may be introjected at any point throughout life and, if not reexamined in the process of later development, remain unassimilated or not integrated into the Adult ego state. The Parent ego states constitute an alien chunk of personality, imbedded within the ego and experienced phenomenologically as if they were one’s own, but, in reality, they form a borrowed personality, potentially in the position of producing intrapsychic influences on the Child ego states.

The Adult ego consists of current age-consistent emotional, cognitive, and moral development; the ability to be creative; and the capacity for full contactful engagement in meaningful relationships. The Adult ego accounts for and integrates what is occurring moment-by-moment internally and externally, past experiences and their resulting effects, and the psychological influences and identifications with significant people in one’s life.

The object relations theories of attachment, regression, and internalized object (Bollas, 1979, 1987; Fairbairn, 1952; Guntrip, 1971; Winnicott, 1965) become more significant when integrated with the concepts of the Child ego states as fixations of an earlier developmental period and the Parent ego states as manifestations of introjections of the personality of actual people as perceived by the child at the time of introjection (Erskine, 1987, 1988, 1991).

The psychoanalytic self psychology concept of selfobject function (Kohut, 1971, 1977) and the Gestalt therapy concept of defensive interruptions to contact (Perls, Hefferline, & Goodman, 1951) can be combined within a theory of ego states to explain the continued presence of separate states of the ego that do not become integrated into the Adult ego (Erskine, 1991).

Ego state theory also serves to define and unify the traditional psychoanalytic concepts of transference (Brenner, 1979; Friedman, 1969; Langs, 1976) and non-transferential transactions (Berne, 1961; Greenson, 1967; Lipton, 1977).

Transference within an integrative psychotherapy perspective of ego states can be viewed as:

1. the means whereby the client can describe his past, the developmental needs which have been thwarted, and the defenses which were erected to compensate

2. the resistance to full remembering and, paradoxically, an unaware enactment of childhood experiences

3. the expression of an intrapsychic conflict and the desire to achieve intimacy in relationships, or

4. the expression of the universal psychological striving to organize experience and create meaning.

This integrative view of transference provides the basis for a continual honoring of the inherent communication in transference as well as a recognition and respect that transactions may be non-transferential (Erskine, 1991).

Script

The concept of script serves as the third unifying construct and describes how as infants and small children we begin to develop the reactions and expectations that define for us the kind of world we live in and the kind of people we are. Encoded physically in body tissues and biochemical events, emotionally, and cognitively in the form of beliefs, attitudes, and values, these responses form a blueprint that guides the way we live our lives (Erskine, 1980, 2010a).

Eric Berne termed this blueprint a “script” (1961, 1972) and Fritz Perls, innovator of Gestalt therapy, described a self-fulfilling, repetitive pattern (1944) and called it “life script” (Perls & Baumgardner, 1975). Alfred Adler referred to this as “life style” (Ansbacher & Ansbacher, 1956); Sigmund Freud ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction Philosophical principles of integrative psychotherapy

- Chapter One Integrative psychotherapy: theory, process, and relationship

- Chapter Two A therapy of contact-in-relationship

- Chapter Three Attunement and involvement: therapeutic responses to relational needs

- Chapter Four Psychotherapy of unconscious experience

- Chapter Five Life scripts and attachment patterns: theoretical integration and therapeutic involvement

- Chapter Six Life scripts: unconscious relational patterns and psychotherapeutic involvement

- Chapter Seven The script system: an unconscious organization of experience

- Chapter Eight Psychological functions of life scripts

- Chapter Nine Integrating expressive methods in a relational psychotherapy

- Chapter Ten Bonding in relationship: a solution to violence?

- Chapter Eleven A Gestalt therapy approach to shame and self-righteousness: theory and methods

- Chapter Twelve The schizoid process

- Chapter Thirteen Early affect-confusion: the “borderline” between despair and rage

- Chapter Fourteen Balancing on the “borderline” of early affect-confusion

- Chapter Fifteen Relational healing of early affect-confusion

- Chapter Sixteen Introjection, psychic presence, and Parent ego states: considerations for psychotherapy

- Chapter Seventeen Resolving intrapsychic conflict: psychotherapy of Parent ego states

- Chapter Eighteen What do you say before you say goodbye? Psychotherapy of grief

- Chapter Nineteen Nonverbal stories: the body in psychotherapy

- Chapter Twenty Narcissism or the therapist’s error?

- References

- Index