![]()

Lady Gaga exploded onto the popular music charts in 2008, selling millions of CDs, cycling through hundreds of dramatic and provocative costumes, and achieving a level of cultural resonance that made her ubiquitous within a year. If you somehow missed her throaty “Ga ga oh la la” on the radio, there’s little chance you also missed the media coverage of her meat ensemble, her egg enclosure, or her Kermit the Frog dress.

One of Gaga’s signature rallying cries is “I’m a free bitch!” But her actions indicate how far from “free” she is. In theory, she can play the music business game however she wants; but if only one path—a path that emphasizes sex and shock value over musical talent—leads to stardom for female artists, so-called artist agency scarcely matters. “Bad Romance,” which won MTV’s Best Video Award in 2009, features Gaga changing clothes 15 times, and then being pawed by a group of women while men watch from a nearby couch.1 As Gaga crawls toward the audience, she sings, “I want your love,” and then dances in her bra and panties before ending up scorched in her bed by the video’s end. If that’s not an allegory for life as a contemporary female popular music star, it probably should be.2

Just prior to releasing ARTPOP in November 2013, Gaga fired her manager, Troy Carter, whom she had worked with on The Fame, The Fame Monster, and Born This Way. The split, widely attributed to creative differences, found Gaga untethered and seemingly desperate. In mid-November, she appeared on Saturday Night Live with accused pedophile and notorious creep R. Kelly3 to duet on a song called “Do What U Want,” during which he did simulated sex pushups on her.4 Then, in March 2014, in her live performance at South by Southwest, Gaga went performance-arty, forsaking pop music for a different kind of expression, which involved presenting herself as a pig on a spit, telling the audience she hadn’t showered in a week, and encouraging her friend, Mille, to vomit neon green liquid all over her.5

Meanwhile, as ARTPOP tanked, Beyoncé had a different kind of surprise in store for pop music, dropping Beyoncé with no warning. Fans scrambled to gain access to it, publicizing the release far and wide in their frantic pursuit. Even though it was released in mid-December, it quickly became the eighth best-selling album of 2013. Beyoncé went on to use all of the alter-ego characters employed on the album to thrill audiences with her awkwardly-named-but-brilliantly-executed Mrs. Carter Show World Tour.

Like Gaga before her, critics and fans have called Beyoncé a true game-changer for women in popular music. From a branding standpoint she is: Her ability to tap into universal narratives and cultural tensions simultaneously makes her powerful, resonant, and rare. But if you look carefully at Beyoncé’s strategically selected props, elaborate choreography, family dynamics, and surprise releases, what she really sells is a modern adaptation of the sexual fantasy offered by many of her peers—differentiated by a dash of goddess imagery/marital kink, a heap of vulnerability, and a series of exciting art installations. Beyoncé would go on to have parallel “Bad Romance” and “I’m a free bitch” moments—declarations of empowerment tempered, strategically, by time-honored, industry-mandated, sexual pandering.

Take, for example, the song “Partition.” In the chorus Beyoncé implores her lover to “take all of me. I just want to be the girl you like. The kind of girl you like.” This is not Beyoncé demanding to be respected for the complex nuances of her identity. It is Beyoncé saying she wants to be whatever it takes to fulfill someone else’s desire. These lyrics provide a fitting meta-narrative for her life as a female pop star.

Similarly, at the MTV Video Music Awards in 2014, Beyoncé was praised far and wide for standing in front of a 10-foot-tall sign that said “Feminist.” But that moment only lasted 5 or 6 seconds in a performance that exceeded 14 minutes, in which Beyoncé also appeared in front of a sign that read “Cherry,” as in “turn the cherry out,” and danced on a stripper pole—moves more common in contemporary female pop performances.6 The use of feminism was encouraging, yet fleeting, leaving attentive audience members to wonder whether it was a statement of purpose or merely another prop in Beyoncé’s performance.

Having encoded the norms of the industry expertly, Beyoncé and her handlers knew how far to push, and how much to conform. As foreshadowed in Gaga’s “Bad Romance,” Beyoncé had her way with the industry, and it had its way with her. Both emerged from the relationship wealthier, but arguably a little scorched.

Beyoncé knows that in the end her “best revenge” is her “paper,” or the money she can generate through her brand. So on her 2016 follow-up release, Lemonade, she clarified her brand platform, making it more political, distinctive, and meaningfully differentiated, both personally and socially.

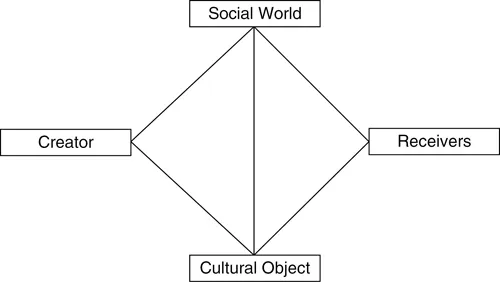

The Cultural Diamond

Beyoncé’s appeal reaches well beyond her music. Her success stems in large part from her ability to represent and empower large groups of people who have historically felt left out of pop cultural narratives and windfalls. Additionally, her pride in her body, her inconsistencies, and her brand empire provide an aspirational model for those struggling with dimensions of their appearance or identity or economic circumstances. Wendy Griswold’s Cultural Diamond (2012) supplies a useful framework for considering the sociological forces that influence the construction and reception of female pop stars such as Beyoncé and their related product offerings. Griswold sets up four points of interaction: the social world, cultural object, creator, and receivers (see Figure 1.1). These four points are critical for understanding any sociological process, as they are inextricably linked and mutually reinforcing.

The social world covers all social interaction, including institutions such as families, schools, or governments, and less organized social relationships. It represents all parts of our constructed social reality, including the aforementioned institutions, those who create symbols and messages, those who receive symbols and messages, and the symbols and messages themselves. The cultural object point on the Cultural Diamond is, for the purposes of this book, the female pop star. (It could also be a specific single or performance, but the artist serves as the dominant unit of inquiry throughout the text for consistency.) The creator point of the Cultural Diamond represents the people who create and distribute the messages and symbols that circulate throughout society. In the music industry, these roles are inhabited by publicists, artist managers, bloggers, photographers, radio programmers, and retailers—basically anyone involved in assembling pop star symbols, images, messages, and narratives. One could also argue that modern artists such as Beyoncé are creators as much as they are cultural objects, as long as we acknowledge that any pop star at or near Beyoncé’s level has legions of people working on her behalf to fastidiously create, maintain, and update her brand. Finally, the receiver point on the Cultural Diamond corresponds with music and pop culture audiences—fans of Beyoncé who follow her for her music, her performances, her narratives, her relationships, her fashion choices, her social agenda, or any combination of these things.

If we accept the relatively stable, mutually reinforcing societal forces presented in the Cultural Diamond, and acknowledge that there are constantly changing social dynamics among the individuals living within them, it makes sense to look for integrated explanations about individual behavior. This search has led scholars from numerous fields to study how symbols, negotiated reality, and the social construction of society aid our general understanding of the roles that people play in society and the reasons for their role choices.

Sociological approaches to cultural production

For our purposes, the Cultural Diamond should be viewed as an umbrella or a container for the other theories presented throughout the book. Griswold notes that it is intended as a framework for all social interaction, and encourages the supplemental use of theories and models to explain more about the nature of the relationships between the points on the diamond.

Two schools of thought from the field of sociology prove useful in explaining the construction, maintenance, and reception of female popular music stars: critical theory and symbolic interactionism. Critical theory is a macro-level perspective that argues that popular culture arises from a top-down approach in which profit-motivated media companies sell the masses mindless entertainment to uphold dominant ideologies, thus controlling and profiting from audiences (Grazian, 2010). Those subscribing to the critical theory approach regard the media industries as able to “manufacture desires, perpetuate stereotypes, and mold human minds” (Grazian, 2010, p46) and to “reproduce social inequality by reinforcing degrading stereotypes of women” (Grazian, 2010, p57). This approach may sound somewhat anachronistic in that it often assumes a helpless audience unwilling or unable to resist the dominant messages of the culture industries. But progressive scholars within this tradition believe in the notion of polysemy, or the idea that a single sign (e.g., word, image, or, for our purposes here, pop star) can have multiple reasonable meanings or interpretations. Nevertheless, these words, images, and symbols exist in a broader production context, which helps to shape at least some of these meanings. Grazian (2010, p61) explained the process by which meanings can become powerful myths that act as cultural shorthand for those receiving them: “cultural hegemony operates at the level of common sense; it is a soft power that quietly engineers consensus around a set of myths we have come to take for granted.” In the world of female pop stars, these myths center around youth, beauty, and sexuality, discussed in greater detail later in the book.

While the critical perspective provides a useful way of understanding the production of popular culture, we must dig deeper into symbolic interactionism and selected theories from sociology/women’s studies/popular culture studies, communication/media studies, and marketing/branding to assemble all the parts necessary to study the way in which female pop stars are created, managed, and received by the various players on the Cultural Diamond.

Symbolic interactionism is a micro-level theory that suggests that neither the audience nor the media system singularly produces popular culture; rather, popular culture arises from the interactions between the various players and positions on the Cultural Diamond. In other words, audiences can resist dominant messages sent by producers, but they can also be influenced by them, as well as by other micro-level influences, such as friends and thought leaders in their given cultural circles.

Symbolic interactionism, named by Herbert Blumer in 1969, developed out of resistance to behaviorism, which held that all behaviors are acquired through conditioning, typically through reinforcement or punishment (Watson, 1913; Blumer, 1986). But the foundations of this type of interactionism, which informs contemporary thinking in communication and sociology, began as far back as 1902, when sociologist Charles Horton Cooley offered the concept of a “looking glass self,” where a person’s view of herself is a reflection of her expectation or imagination of other people’s evaluations of her. In other words, we internalize how we think other people view us into our own self-image. “The imaginations people have of one another,” Cooley (1902, pp26–27) wrote, “are the solid facts of society.” Philosopher George Herbert Mead (1934, 1982)7 used baseball as a way of showing how people learn to play various roles in society, offering that people don’t learn from simple mimicry, but rather from interaction with and reinforcement from one another. (Mimicry wouldn’t work in baseball, as we need pitchers, catchers, first basemen, and all of the other positions, and players need to adapt their behavior for the role/position they play.)

Sociologist and social psychologist Erving Goffman (1959) suggested that the roles people play are essentially scripted for various audiences and that, as people act out such roles, they view themselves through the lens of their perceived audience. Returning to Beyoncé, we can see that how she acts or evolves is (at least in part) based on her interpretation of how she will likely be received by the music industry, fans, and other artists alike. Goffman (1959) would likely classify Beyoncé as a master of “impression management” because, while most people attempt to regulate their self-image to some extent, female pop stars arguably do so consciously and continuously, as their “self” is often a branded commodity. How these various audiences interpret or receive Beyoncé’s actions, music, or narratives depends upon the meanings they ascribe to her, and this is a function of the ever-changing factors discussed above. Audiences also respond to Beyoncé based on their expectations of normative feminine behavior in contemporary society. For example, her decision to release “Formation” challenged the idea in pop stardom, and in American culture, that a woman’s power derives mainly from her attractiveness or sexuality. The messaging in this video provided a different and exciting demonstration of female power, while Beyoncé maintained her aspirational image throughout.

Mead (1982) posited that human beings do not react...