![]()

Part I

Critical parameters

![]()

1

Creative arts and media research

Key terms and perspectives

1.1 Introduction

We are, then, witnessing an increased role for research within the creative arts both within the academy and in the art world itself. The last ten years have in effect seen a reconceptualization of the creative practice project as a research-led exercise. Moreover, contemporary art practice and teaching are no longer tied to craft specifics and the mysteries of individual media. Conceptual activity and practices of research and development are now at the core of art and media education.

But how does artistic research fit into the broader field of academic research? What might be the basis for a systematization of its methods? For instance, can creative arts research methods be taught? Is it appropriate to try to systematize research methods in an area as singular as the creative arts? Does the emphasis within arts education on individual imagination and expressivity and on the creative development of the artist mean that artistic research is beyond the scientific pale?

1.2 Defining the key terms

Research is a portmanteau term with a number of meanings. For example, when we employ the internet and world wide web to conduct a series of informational searches for cheap air tickets, best web buys or possible partners, we now refer to this activity as “research”. The dictionary definition of the term focuses more on the systematic character of research as a knowledge-gathering activity, characterizing it as “an endeavour to discover new or collate old facts etc. by the scientific study of a subject or by a course of critical investigation”.1

This definition seems sufficiently wide to incorporate the creative arts. However, it is probably true to say that this and other standard definitions of research have at their core a privileged meaning, and this is related to notions of scientific investigation. Scientific research is held to follow certain methodological procedures involving observation, objective data gathering and quantification. It provides generic explanations rooted in substantiated bodies of theory. These empirical methods underwrite the validity of science’s knowledge claims (the logic of scientific discovery is examined in Chapter 4). It is argued that there is a unity of scientific method. So, ideally, all research activity should adhere to this model, including artistic research.

In addition, for research to be judged worthwhile in character, it should have a measure of originality and contribute something new and innovative to the field of investigation. It should come up with fresh empirical or theoretical findings which advance our knowledge in a field or apply existing knowledge to generate new practical outcomes of value, such as the technological sciences and design research do. Artistic research actually scores pretty well on the criteria of originality. Though, as we might expect, it is the originality of the artwork produced, whether painting, performance, film, composition or design, that is highly valued in arts research rather than any general conclusion or knowledge claim.

Of course, when we invoke the criteria of systematicity, artistic research seems to immediately run into problems. Research in the arts tends to follow an open discovery path (though often in the area of media arts, this is guided by professionally established codes of production). Its focus is primarily on the making of a unique art object or media artefact and only secondarily on reflecting upon this process with a view to arriving at any set of abstract generalizations.

The exception is perhaps advanced art education. Here, as we shall see, students undertaking creative project work are encouraged to treat the studio as a laboratory of sorts. And, as we shall see, historically it has been the pedagogic challenges associated with modernist art education that have provided the basis for an emergent research tradition within the visual arts. Thus, while there has been much talk within art discourse about the experimental nature of contemporary art, and a corresponding fondness for conceiving of the studio as a laboratory and the art process as an investigative activity, this use of scientific terminology within the creative sphere is largely metaphorical. The mode of understanding in the arts tends to focus on the specifics and materiality of the art process and on the production of an artefact, proposition or performance, rather than on the sort of law-like generalizations to which the natural sciences and some of the social sciences aspire. Yet to count as research within the academy, artistic research has to be seen as conforming – to some extent – to the established protocols of science.

This privileging of objectivist scientific method in the conduct of research and conceptualization of knowledge is often referred to as positivism. This powerful, indeed, “imperial” theoretical position (examined in depth in Chapter 4) plays a dominant role within the broad research community. With its roots in philosophy’s early twentieth-century accommodation to the rise of the natural sciences, positivism seems to want to legislate methodologically for other domains of enquiry, such as the arts and social sciences. Often it appears to have the institutional power to do so, despite the fact that a field like the creative arts does not seem at all to conform to the rationalist and nomological (law-like) character of the natural sciences.

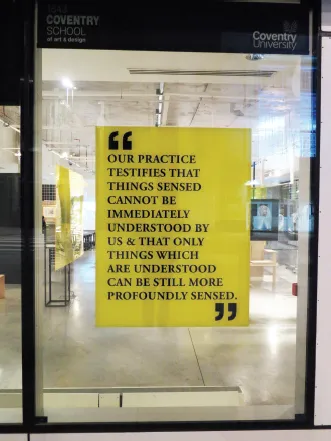

Moreover, this totalizing position is often what gets us into trouble when we seek to model artistic research. “Stupid as a painter” goes the age-old denigration of artistic intelligence. Certainly, in the past the work of visual artists was often unfavourably compared with the forms of rationality deployed by scientists and writers. But artists, I will argue, have a special way of seeing and understanding the world through their practice. Artistic research seeks to recognize and formalize the work of the “thinking eye” and the artist’s sensory engagement with the world. To quote the motif displayed on a poster prepared by the artwork collective Jeffrey Charles Henry Peacock for their 2014 Lanchester Gallery Projects (Figure 1.1) “our practice testifies that things sensed cannot be immediately understood by us and that only things which are understood can be still more profoundly sensed.”

By artistic research, I mean the research that artists do as artists, rather than the research that is done on them and their work by critical scholars. I prefer this term to the clumsier couplets practice-based arts research or practice-led research or, indeed, to the term practice as research. The notion of artistic research seems to acknowledge art activity as a fusion of creative and critical elements. It rejects any attempt to drive an analytical or institutional wedge between the acts of making and of theorizing. In the first instance, by theorizing I mean the process of providing a critical context for one’s creative work so that both its creative intent and communicational achievement can be understood and evaluated by others (in part by placing it alongside comparable work in the field and in part by setting it into conversation with various critical discourses and interlocutors and giving the work a social and historical context). This text champions the idea that practice can provide both an empirical and critical basis for theorizing arts and culture.

Figure 1.1 JCHP poster, Critical Décor: What Works Exhibition, Lanchester Galleries, Coventry, 2014

In part, the notion of “theory” employed in creative arts research and pedagogy refers to the importation of general sociological concepts, models of mass communication process and forms of cultural analysis into the fields of media, communication and cultural studies. But it is also used in a more specific manner within media arts and in studio-based art education to refer to the analysis of cultural representation and of semiotic and ideological processes and to privilege this field of investigation over other approaches to researching the creative arts. In this latter case, the term critical theory is often invoked to qualify the notion of theory employed. And, in this guise, the notion draws upon a varied body of sophisticated critical and philosophical theory, much of which is derived from French poststructuralist and deconstructionist sources (Roland Barthes, Jacques Lyotard, Julia Kristeva, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Gilles Deleuze, Helene Cixous – to list but a few of the luminaries whose work is often drawn upon).

However, the notion of critical invoked in artistic research is a complex one with at least three, often overlapping, meanings.2 Firstly, the term alludes to the classic Enlightenment concern with the rational foundations of scientific and other forms of knowledge. In the case of the creative arts, the focus is often on the basis of aesthetic judgements. Philosopher Immanuel Kant sought to identify the conceptual foundations of Newtonian physics and expose the limitations of metaphysical thinking in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781/2007). Kant was also concerned with the rational basis of moral reasoning and of aesthetic judgement.

The second use refers to the radical critique of political economy and capitalist society advanced by Karl Marx. This approach envisages a form of social and political theory committed not only to understanding the structure and dynamics of capitalist development but also to providing the scientific basis for transforming society. A later generation of social theorists, associated with the Institute for Social Research in Weimar Germany, sought to extend Marx’s analysis to the broader study of social domination. They began to use the term critical theory to discriminate their radical approach to social and cultural theory from positivist accounts of social science method.

Lastly, the term critical has been used to refer to traditions of exegetical scholarship and cultural evaluation, that is to say, to practices of criticism or critique.3 With its origins in biblical interpretation, from the eighteenth century the term spread to the assessment of cultural works – books, plays, performances, exhibitions – by specialist intellectuals operating within the sphere of public culture. The critic sought to understand and evaluate the merits of a text or form of discourse or artwork, performance or proposition in a reading shared with an interested audience to whom they offered a considered judgement. As Raymond Williams points out (1976:75), such judgements became associated with an ability to “discriminate” in matters cultural. Thus, the term became inextricably connected with questions of taste and distinction:

criticism in its specialized sense developed towards TASTE (q.v.), cultivation, and later CULTURE (q.v.) and discrimination (itself a split word, with this positive sense for good or informed judgment, but also a strong negative sense of unreasonable exclusion or unfair treatment of some outside group – cf. RACIAL).

Creative art and media students are pretty familiar this third use of “criticism”. After all, since the end of the nineteenth century, the “crit” has been institutionalized within the art school as a key pedagogic tool central to studio-based learning. The crit, or critical review, is a one-on-one tutorial meeting between student and tutor – or a group tutorial encounter between tutors and a group of students. Work is presented to a tutor for comment and in some cases to industry practitioners (common in architecture, design, film and photographic education). The aim is to strengthen the development of the student’s work and their insight into art and design processes more generally.4 The crit is designed to provide feedback and evaluation of a student’s creative work and to more generally foster a spirit of self and peer criticism on the part of students. Students are expected to communicate the creative intent of their work and identify its artistic and intellectual auspices to their tutor, who, in turn, seeks to objectively comment on work presented.

I use the term creative art 5 to refer to the broad range of studio-based arts disciplines concerned with “making and doing” – the visual arts and design; the lens and screen-based arts forms, such as film and photography; performance, literary and sonic art activities, such as drama, dance, music making and creative writing; and all the hybrid forms that mix and merge these practices. The couplet creative arts and media acknowledges a common field of professional and educational practices concerned with invention and creation. Indeed, that commonality at least in part rests on the widespread use of a range of lens and screen-based media across a range of arts disciplines. It also rests on the conceptualist character of much contemporary art. Ideas, rather than the use of specific media or production techniques, now drive most contemporary art projects. The notion of studio I use here is a broad-based one incorporating the traditional artist and designer’s atelier, but also the photography and film studio, the performance workshop and adapted gallery space, the writer’s study and the multimedia workspace – in short, anywhere creative projects and practices are originated, developed and delivered and ideas and creative strategies are explored and implemented to produce creative work.

Figure 1.2 William Kentridge, More Sweetly Play the Dance, multiscreen installation, Luma Gallery, Arles 2016

Figure 1.3 More Sweetly Play the Dance close-ups

Again, I do not wish to draw any hard and fast lines between fine and applied art, or between the visual arts and the media and performing arts. Today the creative arts are increasingly interdisciplinary in character with elements of performance, installation, lens-based imaging, blending with the traditional concerns of the painter, sculptor, musician, film-maker and photographer.

For example, in the summer of 2016 the South African artist–film-maker William Kentridge exhibited a multiscreen installation More Sweetly Play the Dance at the Luma Foundation gallery in Arles in the south of France (Figures 1.2/1.3), a piece previously shown at the EYE Film Museum in Amsterdam and reported on in a book with the same title (Kentridge 2015).

This tableau vivant portrays a caravan of dancers, marching bands and animated figures that winds its way past the viewer across eight assembled cinema size screens over 40 metres in length in a riveting Dans...