Introduction

South Korea is a nation of extreme changes, rigidities, complexities, intensities, and imbalances. According to World Bank data, South Korea’s nominal per capita GDP was a mere 156 US dollars in 1960 (World Bank 2016). It rose to 27,970 US dollars in 2014 thanks to several decades of explosive economic growth (and despite a few intermittent economic crises). World Bank data also show that the volume of the entire national economy in 2005 ranked South Korea at the world’s 11th, between India and Russia, and this ranking was largely sustained until recently. This process of explosive economic growth has been accompanied by a thundering restructuring of society. The urban population (in official urban districts called dong) was only 28.0 percent in 1960 but kept bloating to reach 81.5 percent in 2005, a level sustained for the following decade (KOS IS 2016).1 Private domains of life have not been exempted from radical alteration. South Korean women shocked the world (and South Koreans themselves) by recording a total fertility rate of 1.076 in 2005, the world’s lowest except the two city states, Hong Kong and Macao, whose citizens were agonizing about their uncertain futures under China’s new rule (NSO 2 006; World Bank 2016). The highest total fertility rate in South Korea was recorded in the early 1960s (6.0 in 1960).

Having recorded historically and internationally unprecedented changes in their society and life, the same South Koreans have stubbornly resisted certain significant changes. Above all, having become the world’s most rapidly aging population, most South Koreans continued to regard elderly care as the exclusive domain of filial piety. In 1998, when South Koreans had to confront an unprecedented national financial crisis, as many as 89.9 percent of them reportedly considered elderly care as the sole responsibility of children (KOSIS 2016). However, the widespread and prolonged material hardship for both young and old people in post-crisis South Korea would rapidly reduce this proportion to 33.2 percent in 2012 and induce 48.7 percent of South Koreans to demand familial-social-governmental co-responsibilities in the same year. Perhaps not unrelatedly, the supposedly traditional norm of son preference was intensely manifested until the final years of the 20th century, but it would gradually become insignificant thereafter. The sex ratio at birth remained at levels higher than 110 during most of the 1990s (except 109.6 in 1999), but has suddenly been attenuated so as to approximate the so-called “natural” level of 105 in recent years (KOSIS 2016). These enduring features of South Korea in tandem with explosive changes in many other aspects have inevitably made the country an extremely complex social entity for which no easy sociological account is available.

The miraculous transformations and tremendous complexities of South Koreans’ economic, social, and political life have required South Koreans to devote astonishing amounts of time and energy for national and/or individual advancement (or for sheer adaptation and survival). According to the OECD, South Koreans were the only people on earth working more than 2,000 hours yearly as of 2007 (2,261 hours on average) (OECD 20 08). South Korea has continued to remain at similar levels even though a few other countries under economic hardship (e.g. Mexico, Greece) have joined the 2,000-plus working-hour club. Before toiling in the labor market, South Koreans have to go through no less spartan processes of studying, and almost all students advance to next levels of schooling up to college (NSO 200 5; World Bank 2016). Relatedly, numerous international surveys have shown that South Korean youth study longer and sleep less than most of their counterparts in other industrialized societies (National Youth Policy Institute 2009; OECD 20 09).

In spite of – or perhaps because of – such devotion to work and study at internationally unrivalled levels, South Koreans have been endemically subjected to critical social imbalances in terms of social, physical, and spiritual risks, again at internationally incomparable levels. Among 20 OECD member countries with available data for 2005, South Koreans were least satisfied with their job (68.6%), with the French (70.5%) and the Japanese (72.4%) trailing behind (OECD 2009). More seriously, the number of safety-related deaths per hundred thousand workers was 12.4 in 2007, the largest among all 30 member countries of the OECD (Nocutnews 15 July 2008). Both industrial accidents and traffic accidents contributed to this gruesome dimension of South Korean development. Despite a sustained rise in life expectancy, South Koreans’ health conditions continue to suffer from what they call “backward country symptoms.” As of 2011, South Korea was the only OECD member country with more than 100 tuberculosis incidents per 100,000 people despite a gradual decline thereafter – 101 in 2011, 96 in 2012, 90 in 2013, and 86 in 2014 (WHO 2016). Furthermore, South Koreans inflict fatal harm on themselves at one of the highest levels in the world – e.g. 29.1 out of 100,000 South Koreans committed suicide in 2012, the highest level among all OECD countries (WHO 2016). Age-adjusted data on suicide in 2014 ranks South Korea at the world’s third (29.34 per 100,000 people) after Guyana (43.22) and North Korea (37.44).

It is hard to imagine this society used to be called a “hermit kingdom” when it was first exposed to Westerners. How can social sciences, sociology in particular, deal with this miraculous yet simultaneously obstinate and hystericalized society? Social sciences in general have been employed from the West, especially the United States, and dispatched to South Korean realities throughout the postcolonial era (Park and Chang 1999). Besides hiring Koreans with academic degrees from major Western universities for most faculty positions, renowned Western social scientists have frequently been invited and oftentimes begged to speculate upon South Korean realities. But borrowed Western social sciences in the South Korean context, no matter how much adapted locally, have critically added to the complicated nature of South Korean modernity by inundating this society with hasty speculative prescriptions under the rubric of Westernizationcum-modernization. Many South Korean scholars have responded to this dilemma by proposing the construction of “indigenous social sciences” or “Korean-style social sciences” (Shin, Y. 1994). However, South Korean society’s distinctiveness since the last century seems to consist much more critically in its explosive and complex digestion (and indigestion) of Western modernity than in some isolated characteristics inherited from its past.

A globally grounded comparative modernity approach to what I conceptualize as compressed modernity – drawing insights from critical debates on postcolonialism, multiple modernities, reflexive modernization, and postmodernity – is called for. Compressed modernity is a critical theory of postcolonial social change, aspiring to join and learn from the main self-critical intellectual reactions of the late 20th century as to complex and murky social realities in the late modern world. Such intellectual reactions include postmodernism (e.g., Lyotard 1984), postcolonialism (e.g., Chakrabarty 19 92), reflexive modernization (Beck, Giddens and Lash 1994), and multiple modernities (Eisenstadt 200 0). Postmodernism forcefully argues that modernity has exhausted or abused its progressive potential, if any, only to spawn deleterious conditions and tendencies for humanity and its civilization and ecological basis. Postcolonialism cogently reveals that postcolonial modernization and development have been far from a genuinely liberating process due to the chronic (re)manifestation of colonial and neocolonial patterns of social relations and cognitive practices in the supposedly liberated Third World. Reflexive modernization in late modern reality, as argued by Beck, Giddens, and Lash, is a structurally complicated process of social change under the uncontrollable floods of choices that expose modern society and people to more risks than opportunities. The multiple modernities thesis emphasizes a comparative civilizational perspective that can help recognize variegated possibilities and forms of modernities in the diverse historical and structural contexts for nation-making or national revival. As directly indicated or indirectly alluded to below in this chapter, all of these critical debates on modernity have essential implications for the compressed modernity thesis.

Since the early 1990s, I have tried to argue that compressed modernity can help to construe, one the one hand, the extreme changes, rigidities, complexities, intensities, and imbalances in South Korean life and, on the other hand, analyze interrelationships among such traits and components. In a rapidly increasing body of international research on South Korea and East Asia, the concept of compressed modernity has been widely adopted as a conceptual/theoretical tool for organizing and interpreting empirical findings in various lines of social research.2 In this chapter, I intend to present a formal definition and core theoretical components of compressed modernity, point out historical and structural conditions for compressed modernity, and discuss the historical and theoretical relevance of compressed modernity beyond the South Korean context.

Compressed modernity in perspective

Definition

Compressed modernity is a civilizational condition in which economic, political, social, and/or cultural changes occur in an extremely condensed manner in respect to both time and space, and in which the dynamic coexistence of mutually disparate historical and social elements leads to the construction and reconstruction of a highly complex and fluid social system (Chang 2015). Compressed modernity, as detailed subsequently, can be manifested at various levels of human existence and experience – that is, personhood, family, secondary organizations, urban/rural localities, societal units (including civil society and nation), and, not least importantly, the global society. At each of these levels, people’s lives need to be managed intensely, intricately, and flexibly in order to remain normally integrated with the rest of society.

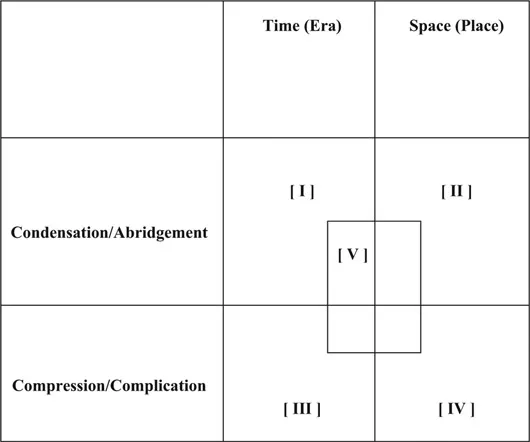

Figure 1.1 shows that compressed modernity is composed of five specific dimensions that are constituted interactively by the two axes of time/space and condensation/compression. The time facet includes both physical time (point, sequence, and amount of time) and historical time (era, epoch, and phase). The space facet includes physical space (location and area) and cultural space (place and region). As compared to physically standardized abstract time-space, era-place serves as a concrete framework for constructing and/or accommodating an actually existing civilization.3 Condensation/Abridgement refers to the phenomenon that the physical process required for the movement or change between two time points (eras) or between two locations (places) is abridged or compacted (Dimensions [I] and [II] respectively). Compression/Complication refers to the phenomenon that diverse components of multiple civilizations that have existed in different areas and/or places coexist in a certain delimited time-space and influence and change each other (Dimensions [III] and [IV] respectively). The phenomena generated in these four dimensions, in turn, interact with each other in complicated ways and further generate different social phenomena (Dimension [V]).

Figure 1.1 Five dimensions of compressed modernity

The above schema of differentiating time and space and separating condensation and compression needs a logical justification. In a non-Western historical/social context in which Western modernity is conceived as the core source of civilizational as well as politico-military superiority, the West stands not only as a discrete region but also as a discrete (but prospectively own) moment of history. Where indigenously conscious efforts for civilizational rebirth are defeated by external forces or frustrated internally, the West often becomes both a direction for historical change (modernization) and a contemporaneous source of inter-civilizational remaking (Westernization in practice). The more condensed these changes become – that is, the faster modernization proceeds and the fuller Westernization takes place – the more successful the concerned countries tend to be considered (in spite of cultural and emotional irritations, as well as political and economic sacrifices experienced by various indigenous groups). However, the very processes of modernization and Westernization endemically induce the cultural and political backlashes on the part of the adversely affected groups and, in frequent cases, systematically reinforce the traditional/indigenous civilizational constituents as these are deemed ironically useful for a strategic management of modernization and Westernization. Thereby compression becomes inevitable among various discrete temporal and regional civilizational constituents.

Constitutive dimensions

The five dimensions of compressed modernity (in Figure 1.1) can be explained in terms of South Korean experiences in the following way. Time (era) condensation/abridgement (Dimension I) can be exemplified by the case that South Koreans have abridged the duration taken for their transition from low-income agricultural economy to advanced industrial economy on the basis of explosively rapid economic development. The rapid changes so often discussed in connection with South Korea – such as the “compressed growth” of the economy and the “compressed modernization” of society – belong to this dimension. That is, compressed modernization is a component of compressed modernity. Such compressed (condensed) changes are also apparent in the cultural domain, so that even postindustrial and/or postmodern tendencies are observed in various sections of society. South Koreans’ pride that they have supposedly achieved in merely over half a century such economic and social development carried out over the course of two or three centuries by Westerners has been elevated to the level of the state. The South Korean government has been busy publishing numerous showy statistical compilations that document explosive economic, social, and cultural changes for the periods “after liberation,” “after independence,” and so on (NSO 1996, 1998).

South Koreans’ success in condensing historical processes, however, does not always reflect the outcome of voluntary efforts but, in numerous instances, has simply resulted from asymmetrical international relations in politico-military power and cultural influence. For instance, no other factor was as crucial as the American military occupation during the post-liberation period for their overnight adoption of (Western-type) modern institutions in politics, economy, and education (Cumings 1981). Nowadays, even the postmodern culture has been instantly transposed on to South Koreans through internationally dependent media and commerce (Kang 1999). Even in those areas in which voluntary efforts have been decisive, targeted end results do not alone tell everything. For instance, if one drives between Seoul and Busan taking ten, five, or three hours respectively, the driver (and passengers) will feel differently about the trip in each case and the probability of experiencing accident and fatigue from driving cannot but differ as well. We should analyze South Koreans’ experience of overspeeding towards development y focusing on the very fact of their overspeeding.

Space (place) condensation/abridgement (Dimension II) can be exemplified by the fact that the successive domination of South Korea by various external forces in the last century compelled the country to change in diverse aspects ranging from political institutions to mass culture under the direct influence of other regions (societies) no matter what geographic distances and differences existed. After South Koreans were physically subdued by colonial or imperial external forces, many ideologies, institutions, and technologies engendered in dissi...