- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume in the seminal Encyclopaedia of Psychoanalysis Series is a daring reassessment of the psychoanalytic theory of phobia from numerous schools of thought. This book should illuminate why psychoanalysis has been under-used in the treatment of phobia - is it simply that other treatments are more successful or is it a symptom of today's "quick fix" culture? By considering the origins and meanings of phobia from such a wide range of viewpoints, it may be possible to formulate new approaches to the therapeutic treatment of phobia and re-engage the interests of the psychoanalytic community in this fascinating subject. 'In recent years research, theorization, and the treatment of phobias have been dominated by biological and psychopharmacological approaches, and by cognitive-behavioural therapies. Writings on phobia have diminished in the field of psychoanalysis. This book is an attempt to redress the balance and focuses not on treatment but on the origin and meaning of phobia. This collection, then, concentrates on the personal, mythological and cultural meanings of phobia and its origins' - The author from her Introduction.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Phobia: a biological perspective

Richard J. Evans

Phobias are characterized by fear or anxiety which is: (1) persistent; (2) out of proportion to the actual danger and demands of the situation; (3) cannot be explained or reasoned away; (4) is beyond voluntary control; (5) leads to avoidance of the feared situation; and (6) is in some degree disabling (Marks, 1969; Kräupl Taylor, 1979).

Phobias are a broad, non-homogenous range of conditions, of which anxiety and fear are the main features (Bowlby, 1973). Readers may already be well aware that agoraphobia, social phobia and the specific (or simple) phobias are all significantly different from each other, despite the way they are drawn together in common parlance under the generic term "phobia". Although the definitions used in the two major psychiatric classification systems—DSM-IV and ICD-10—are not entirely congruent, it is clear that in both the main characteristic of specific phobias is avoidance arising from the fear of—or anxiety about—a specific object or situation. There is no significant association between specific phobias and panic attacks. In the DSM-IV classification, avoidance in agoraphobia is regarded as commonly arising from the experience of panic attacks, with subsequent anxiety focused upon situations in which they might occur, and upon the possibility of loss of control. Although DSM-IV allows a diagnosis of agoraphobia without panic attacks, this is a rare occurrence and probably artefactual (Andrews et al., 1994). ICD-10, meanwhile, presents a diagnostic definition of agoraphobia which is closer to that of specific phobia than DSM-IV. Nonetheless, the two systems probably do not diverge too far from each other when applied in clinical practice (Andrews et al., 1994).

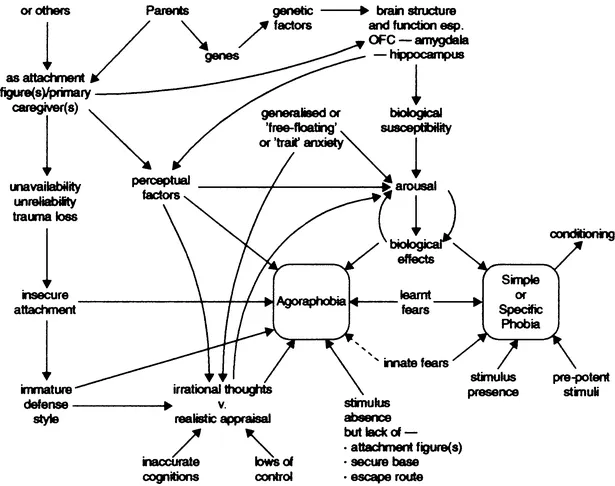

Figure 1 summarizes a proposed overview of mechanisms in the genesis of agoraphobia and specific phobia. It also attempts an integration of perspectives drawn from neurophysiology, ethology, evolutionary psychology, and attachment theory, as well as epidemiological research on susceptibility to anxiety disorders and studies on the nature of perception.

Figure 1 suggests that specific phobia is the less complicated clinical picture. It can probably be understood relatively easily in terms of both aetiology and pathogenesis. Agoraphobia is more multifactoral in origin. Given the number and complexity of its contributory factors, and the vulnerability which they impart, it is perhaps not surprising that there is extensive co-morbidity of agoraphobia with other psychological abnormalities—notably with depression and substance abuse. This co-morbidity is rare in the specific phobias, which can occur in individuals who are otherwise stable and psychologically well (Mavisakalian & Barlow, 1981a).

Another way of viewing this is to regard the panic disorder/ agoraphobia/claustrophobia cluster as elements of a more diffuse disturbance characterized by generalized or "free-floating" anxiety. This is not a common feature of specific phobias, but is present in agoraphobia and the related conditions (Lader & Marks, 1971). However, what the specific phobias have in common with the cluster of other disorders is the triggering of fear and anxiety. Associated with these affective responses are the pronounced biological reactions which give rise to the well-recognized signs and symptoms of both types of disorder.

The aim of this chapter is to introduce psychoanalysts, psychotherapists, and counsellors to aspects of biology—particularly neurobiology—which are relevant to the understanding of phobia. In particular, this chapter considers the physiology of stress, fear, and anxiety, in the context of panic-disorder/agoraphobia/ claustrophobia, and of the specific phobias.

Figure 1. Contributory factors and mechanisms in the genesis of agoraphobia and simple phobias: a preliminary integration. Whilst there are some common factors it is apparent that innate fears and pre-potency are predominantly important for the development of simple phobia rather than agoraphobia. A significant difference is that for simple phobia the trigger stimulus is usually present in circumstances which activate fear, whereas agoraphobia is associated with an absence of security. Many more factors contribute to the development of agoraphobia, including attachment factors. Familial environment will contribute via genetic and interpersonal effects and these require further discrimination, particularly since there is likely to be strong interaction between them. There may prove to be some redundancy in the figure upon further investigation, for example, since factors represented separately may prove to be related or identical.

The evolutionary role of fear

Fear is a necessary and valuable behavioural response. Fear—alongside other innate and learned avoidance responses—is apparent in a very wide range of species of animals, as well as in human beings. It is essential to surviving the hazards of the environment. However, the dangers which confront all neonatal animals—when they are generally in the care of a parent, and often in some form of nest environment, either singly or alongside littermates or siblings—are clearly quite different from those which will face them as they become more independent and venture more widely into the environment. The early hazards of this exploratory phase may, once more, differ markedly from the dangers of adult life. Consequently, fearful responses to a wide variety of circumstances and stimuli, appropriate to these different stages in development, may be expected to possess survival value by restraining risky behaviour. The way in which key biological molecules and functions have been strongly conserved across evolutionary time and species appears to confirm this. In their examination of the evolutionary aspects of anxiety disorders, Stevens and Price (2000) argue for the importance of such archaic threats. Whilst some experimental studies support the interpretation that evolutionary-relevant fears are easy to establish and resistant to extinction (Ohman et al., 1985; Öhman and Soares, 1993), other studies (Cook et al., 1986; McNally & Foa, 1986) suggest that these findings are not robust.

Innate and learned responses

One might argue that, from an evolutionary perspective, some fearful responses would need to be innate, in order to deal with immediate dangers, such as predation. In later life the need to range more widely in order to find water, food, and mates will introduce new hazards, which do not concern the neonate, in which learning may play an important role. The distinction between innate and learned fear-responses is a teleological division. Almost invariably there is interaction between innate mechanisms and learning processes, so that individual animals may become well adapted to the local environment, and to the particular spectrum of possible hazards which that environment presents. In general, the more relevant a fear-response is to early life, or to hazards likely to be prevalent in later life (for example: snakes), the more likely it is to be predominantly innate. Marks (1969) and Seligman (1971) have suggested that fears of certain stimuli possess prepotency—that is, they are evolutionarily "prepared" such that they allow rapid learning of responses, particularly when they occur coincident with other dangerous, stressful or noxious stimuli.

Many ethological and experimental psychological studies have supported the existence of a range of innate (instinctual) fears in neonates. There has been considerable interest in the ability of neonatal and infant animals to detect exposure to predators or predator-like stimuli, and to make a fear-response. There is, however, debate on the extent to which the visual features of a stimulus (for example: hawk-like silhouettes presented to ducks or geese) are important, as opposed to the novelty of the stimulus to the observer.

The Cambridge ethologist R. A. Hinde (1954) made a detailed study of the interactions between chaffinches and owls, which supports the notion of the existence of innate fears and also demonstrates the conflict between opposed tendencies to approach the predator or to escape from it. Hinde's studies also suggest that hand-reared birds (which have had no opportunity to learn about predators) take around one month from hatching to mount a fear-response to a stuffed tawny owl. This demonstrates that maturation of innate fears can occur without learning playing a part in the process.

Studies of human infants suggest that fear of snakes is innate, but that it does not develop until around 4 years of age and continues to increase until late teenage years (Jones & Jones, 1928). This could be due to maturation or learning. The maturational argument is supported by experiments with chimpanzees, conducted by Donald Hebb (1946a,b), which included both wild and captivity-bred individuals. Hebb found that a model of a snake was one of the most effective stimuli for inducing fear-responses in chimpanzees and that individuals bred in captivity responded in the same way as those which had grown up in the wild. There is evidence that this response is also subject to maturation, reaching maximum intensity at around 6 or 7 years of age. Other fears displayed by chimpanzees—for example, of dead bodies and of strangers—also appear to be innate and to demonstrate maturation. Studies by Mineka and her colleagues (Mineka et al., 1984; Cook et al., 1985; Cook & Mineka, 1989) suggest that in rhesus monkeys, fear of snakes is specifically prepared and that whilst adverse exposure may have a role in the development of active fear, modelling of older monkeys showing fear responses in the presence of a snake was a powerful stimulus. However, in the case of fear of strangers, there is evidence that learning is involved in discriminating familiar individuals.

In human infants, an innate fear of falling (tested by using a "visual cliff" apparatus) can be demonstrated to appear at around 9 months of age. This period is associated with the development of crawling. The fear-response matures over subsequent months and then declines over the period from 2 to 5 years of age (Jersiid & Holmes, 1935).

The existence of innate fears or fear-dispositions suggests that there should be genetically determined variation in levels of fearfulness between individuals within a species. This has been well established in a large number of studies, largely—but not solely—carried out upon laboratory rodents, and analysing a specific unlearnt response to fear, i.e. defecation.

It has been shown that selective breeding can be employed to diversify reactive (or "emotional") and non-reactive (or "nonemotional") strains of rat (see, for instance, Hall, 1951 and Broadhurst, 1975). Further studies have demonstrated that this is not an effect of the maternal pre-natal environment. In studies examining the variation in fearfulness among unselected stock, it appears that genetic factors are responsible for half, or slightly more than half, of the total variation in the population. Differences between the reactive and non-reactive strains of rats have also been demonstrated in passive avoidance behaviour (for example, the reduction in speed of collection of a food-reward which is accompanied by an electric shock), and in the degree of disruption to learning and to performance of learning in the face of a fear-stimulus. These findings indicate that genetic selection affects a class of fearful behaviours, rather than one highly specific response. Experiments examining learnt responses of the reactive and nonreactive rats, in which fear was not an element of the experimental design, revealed no inter-strain difference, confirming the specificity of the genetic selection as fear-based (rather than learning-based).

The variation in the balance between innate mechanisms and learning processes across different fear-stimuli may be relevant to the genesis of phobias, and to the variety of presentations they adopt. For instance, childhood-specific phobias, which often resolve spontaneously, seem more closely related to innate fears than do many adult phobias. Conversely, adult-specific phobias may be due to reactivation of childhood fears under conditions of increased vulnerability, tension or stress. Even so, specific phobias might also be due to conditioning (see p. 29). It is clear that many fear-responses are learnt, and the way in which this may happen is discussed below. Before this a brief resume of neurobiology is necessary.

The nervous system: overview of structure and function

Co-ordination of the majority of bodily processes and responses is under the control of the brain and spinal cord (which together constitute the central nervous system, CNS) and the hormonal system (the endocrine system). Some hormones originate within or are controlled by the brain, particularly by the hypothalamus. Within the brain there are regionally organized collections of nerve cells (nuclei) which subserve specific functions—for example, the regulation of breathing. Thus correlations can often be drawn between functions and specific anatomical regions of the brain. From the CNS, peripheral nerves run out to control muscles, organs, and glands. These nerves can be divided into two main subsystems: the autonomic nervous system and the somatic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system is responsible for the control of "vegetative functions": heart rate, blood pressure, gut motility, airway diameter, and the like. It is further subdivided into sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. The distribution of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems is different but overlapping; many organs are innervated by both, but by no means all of them. The sympathetic system is activated to produce awareness and arousal, in preparation for fight or flight, after a fear-arousing stimulus or during exercise. Increased heart rate and raised blood pressure are amongst the many signs of sympathetic activation. The parasympathetic division is activated when arousal is minimal and vegetative functions—such as digestion—take priority over exertion. The second main system—the somatic nervous system—carries sensation from the skin, skeletal muscle, tendons and joints, and controls the movement of muscle of the limbs and body wall.

Memory

Fear and anxiety evidently have multiple contributory mechanisms and factors. The evidence from ethology and experimental biology shows clearly that there is a contribution from inherent mechanisms. This constitutive element, responsible for innate fears, is most likely to contribute to childhood and specific phobias. The studies on breeding, which made it possible to select rats with differing degrees of anxiety, clearly indicate that general levels of anxiety are genetically controlled. There is also substantial evidence for this in human beings (Andrews et al, 1994). However, fear and arousal are also clearly connected to internal models of external reality, and thus memory is also a central element.

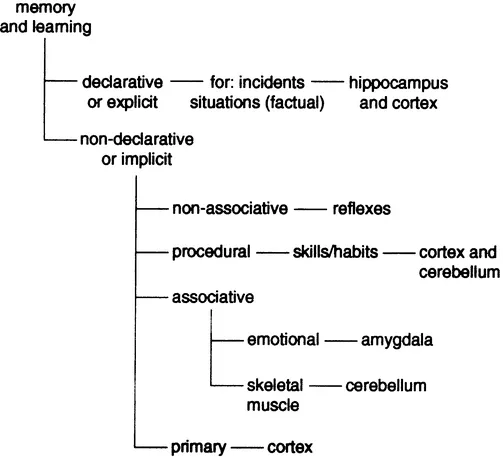

When a threatening or traumatic event occurs it will result in the laying-down of both conscious and unconscious memory-traces. It seems likely that these occur in parallel. It is therefore important to consider memory systems and their operation. Although lay individuals commonly think of memory as a single entity, and psychotherapists will generally think in terms of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious or repressed memory, it is now clear from studies in experimental psychology and neurobiology that there are many memory systems within the brain (Figure 2).

From a neurobiologieal perspective these memory systems may be divided into two main categories. One of them is "explicit, conscious, autobiographical or declarative memory". Essentially, this is memory of facts and events, i.e. of what happened. This memory involves three main brain structures: the hippocampus, the medial temporal lobe, and the cerebral cortex. The other type of memory is "implicit, unconscious or non-declarative memory". This is a collection of procedural memories, i.e. how to operate production of some physiological or psychological response. This memory deals with skills, habits, priming, emotional responses, autonomic skeletomuscular skills (for example, typing), and changes in reflex pathway activity. Emotional and motor skill learning processes are associative, in that they involve learning about causal and temporal relationships between occurrences. Non-declarative learning is localized in many different brain-areas, depending upon which brain area subserves the particular function(s) being learned.

Figure 2. Categorization of different types of memory system identified by experimental studies of learning processes. The brain areas with which they are predominantly associated are also indicated. Modified from Zigmond et al. (2000), Fundamental neu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- FOREWORD

- CONTRIBUTORS

- Introduction

- CHAPTER ONE Phobia: a biological perspective

- CHAPTER TWO High anxiety: a Jungian analysis of phobia

- CHAPTER THREE Phobic anxiety: learning from clinical experience and psychoanalytic observations of children

- CHAPTER FOUR Phobia and object relations theory

- CHAPTER FIVE Phobia as a quest for fantasy

- CHAPTER SIX Phobias and primitive psychotic anxieties

- CHAPTER SEVEN Fathers and phobias: a possibly psychoanalytic point of view

- CHAPTER EIGHT The history of phobia: an overview of the development of ideas on the origins and meaning of agoraphobia

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Phobia by Sian Morgan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.