This is a test

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Looking at the globalization, urban regeneration, arts events and cultural spectacles, this book considers a city not until now included in the global city debate.

Divided into five parts, each preceded by an editorial introduction, this book is an interdisciplinary study of an iconic city, a city facing conflicting social, political and cultural pressures in its search for a place in Europe and on the world stage in the twenty-first century.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

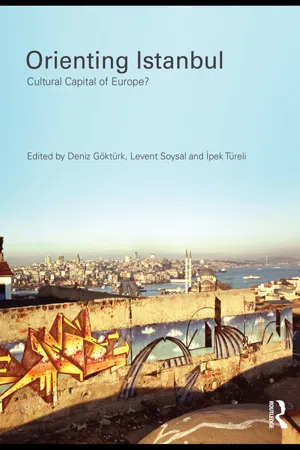

Yes, you can access Orienting Istanbul by Deniz Göktürk, Levent Soysal, Ipek Tureli in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I.

Paths to Globalization

In this opening Part, two seemingly disparate but ultimately complementary chapters locate Istanbul’s paths to globalization and set the agenda for the book. Çağlar Keyder, in ‘Istanbul into the Twenty-First Century’, true to well-established traditions of macro sociology, registers Istanbul’s trajectory to becoming a world city. Engin Işın, in ‘The Soul of a City: Hüzün, Keyif, Longing’, pursues a different course, a literary and photographic expedition, in search of the sources for Istanbul’s vitality at the beginning of the twenty-first century. They seem to be depicting two Istanbuls, worlds apart – for Keyder, a city in the grips of global currents and transformation process, for Işın, a city grappling with its particularities, detached from the world outside. This perfunctory glance is, however, misleading. The Istanbuls narrated in these chapters are not just two sides of the same coin, one socio-economic, the other cultural-aesthetic, but they form a constellation of the world city – in conversation with each other and with other chapters in the book.

Keyder’s purview of Istanbul’s ascendancy to being a global city proper answers the question he himself posed when prefacing his seminal volume Istanbul: Between the Global and the Local: whether Istanbul, then set to typify what he terms ‘informal globalization’, could become a global city. A decade later, his response is solidly affirmative. By the ‘standards’ that gauge a city’s standing in the world hierarchy of cities, Keyder concludes, Istanbul presents a success story. The city is now incorporated into the coveted real estate markets and financial centres; gentrification is continuing at rapid pace; skyscrapers form a discernible skyline; and the cultural landscape of the city offers an enviable diversity of art exhibitions, fashion shows, and festivals, culminating in the designation as European Capital of Culture 2010. Keyder provides a brief history of this success story, succinctly detailing macro transformations that have prepared the city for its new role as a world city, interlaced with a political history of contemporary Turkey since the 1980s.

Işın’s entry point to the discussion is Orhan Pamuk, renowned author of Istanbul, who ascribes the affective label of hüzün to the city in his memoir. In what develops at first as a personal account, walking the streets of Istanbul and capturing daily life at work, Işın grows sceptical of the weight Pamuk attributes to hüzün and proposes keyif (enjoyment of the city) as an alternative that describes the ‘soul’ of the city. Eventually, he concludes that both hüzün and keyif are discursive constructions that ‘orient’ Istanbul, simultaneously ‘orientalizing’ the city as an ‘object of desire’ and ‘Europeanizing’ it by speaking to the Occident through the city. To situate these constructs, Işın turns to the ‘local’ and searches for the ways social groups that inhabit the city deploy them as instruments of governance of the city commensurate with their tastes, habits, and dispositions.

Both Keyder and Iın are concerned with Istanbul’s place and image in a globalized world. Işın finds his objects of study in the representations of Istanbul for audiences in and travellers from the Occident, as well as images of the city that emerge from the everyday practice of the locals. Meanwhile, Keyder is not merely presenting a story of economic transformation; his argument about Istanbul becoming a ‘world city’ is mediated through cultural representations and paradigms that resonate with the images that Işın deliberates over.

A central point of correspondence between the two chapters is circulation. Whether in pictures of the city tinted in hüzün or scenes of keyif, Istanbul images travel the world and bring the world back to Istanbul. These images permeate academic research and artistic expression as well as planning policy and city branding to enhance tourism. Istanbul as narrated by Keyder and Işın is not a city of permanent lives but a city of and for migrants or strangers, who come in search of better fortunes, or of uprooted Istanbulites, now living elsewhere, but nonetheless desiring the pasts embodied and left behind in the city. Like these inhabitants, Keyder and Işın, and several other authors contributing to this book, relate to the city as transient citizens, who maintain homes and jobs in Istanbul and elsewhere. These impermanent lives enable a convergence of perspectives, looking at the city simultaneously as insider (experiential of a citizen) and outsider (looking at Istanbul from afar and comparing it to other cities). Empowered with distanced connectedness to the city, the essays in this and the following Parts propose to decipher and complicate the globalizing ‘success story’ that is Istanbul.

Chapter 1

Istanbul into the Twenty-First Century

Çağlar Keyder

The Globalization Project

During the first decade of the new century Istanbul appeared confident and prospering. There were blocks of newly erected high-rise office buildings, luxury residential compounds and towers, and dozens of shopping malls offering global wares. The city centre was beautified and prepared to anchor global networks. Gentrification of the Beyoğlu area and the historic peninsula, as well as the rebuilding of the waterfront around the Golden Horn, created new spaces of leisure and culture. A feverish pace of projects and plans, all designed to enhance Istanbul’s standing in the global sweepstakes for investment, revenue and culture, coincided with the preparations for the coveted status of 2010 European Capital of Culture. By the standards of city marketing worldwide, Istanbul was a success story.

Back in 1980 Istanbul was a fairly typical Third World sprawl. The old city retained most of its glory and the older neighbourhoods some of their charm, but the overwhelming impression was one of dilapidation and crowdedness. Environmental degradation in the industrial periphery of the city was matched by the lack of urban amenities in the shantytowns; constant construction activity produced the ever-present mud and dust that plagued the streets; and there was an unavoidable gloom of air pollution emanating from old cars and cheap coal. But the city attracted investment and migrants from the countryside, and performed as the principal transmission mechanism for the ‘modernization’ of the peasantry. Istanbul had been responsible for the absorption of a quarter of the new urban population in Turkey during the period from 1960 to 1980. The new migrants could not readily find good employment; but there was a widely shared belief that manufacturing would expand, well-paying jobs would be forthcoming and eventually all households would attain decent comfort. Furthermore, there was provision for the newcomers to access the urban space through informal mechanisms of land occupation and housing construction. As in many cases of Third World urbanization, migrants were permitted to share in the fruits of growth through a politics of populism which suspended the strictures of the law of property. Takings were modest, but their distribution seemed if not fair at least not grossly polarizing.

All this changed when Istanbul, in common with other globalizing cities of the Third World after the 1980s, experienced the shock of rapid integration into transnational markets and witnessed the emergence of a new axis of stratification. Those in the new professions who could participate in global networks gained disproportionately in status and income. Istanbul as Turkey’s primate city in the 1980s was already the centre of high-level services oriented to the national economy. Trade and finance were concentrated in the city, as were the culture and media industries catering to the country as a whole. With globalization and liberalization, however, all these sectors – finance, real estate, advertising and media – experienced explosive growth. Along with culture industries and those service sectors that cater to producers, there was also a resurgence of the art scene, well integrated into global networks. All this growth in activity and employment accelerated with the impetus of tourism which expanded rapidly during the most recent period (now reaching eight million visitors a year), boosted by the city being ‘discovered’ and thus earning a place in the global ‘cosmopolitan’ consciousness.

The predominance of new service sectors and culture industries, even if these account for a smaller proportion of employment in Istanbul compared to London or New York, follows the pattern of de-industrialized global cities around the world. This thin social layer of a new bourgeois and professional class which adopted the lifestyle and consumption habits of their transnational counterparts seems to define a mission for the city, especially because of the obsessive coverage of their lifestyles in the media. The social and cultural ascendance of the new global class is reinforced through carefully cultivated distinctions in lifestyles, residential choice and material consumption, with all the expected ramifications for social and spatial stratification. It is now clearer than ever where the lines of demarcation lie.

The Triumph of Marketing

There is no doubt that Istanbul’s success in capturing a share of the global dazzle is due in large part to the world economy, since the 1980s, favouring the resurgence of the metropolis: this was a period in which the control and management functions of global capital shifted to the great cities of the world and those sectors which are specifically urban gained ground (Scott, 2008). Finance increased its share, real estate development became a leading sector and culture industries expanded. This political and economic shift by itself, however, cannot explain Istanbul’s performance: the world economy provides an opportunity but there is also and always resistance against global projects by the potential losers, the ‘defenders of old space’,1 those who will be displaced socially and spatially. In Turkey’s case anti-globalization was a banner in the hands of the ‘nationalists’ suspicious of the claims of the Davos crowd; for Istanbul this meant the deflation of the global-city project by the land-bound state elite in Ankara. In fact, until the 1990s it looked as if Istanbul would miss the opportunity. Caught between a political class committed to populist modernization and a timid bourgeoisie reluctant to alienate Ankara’s bureaucracy, actors in the city were unable to mobilize significant resources towards global success. Things changed, however, when the conservative-Islamic party which won the local elections in 1994, receiving the bulk of its support from the peripheral neighbourhoods of migrants, proved to be surprisingly pro-business. Their adoption of the neo-liberal discourse found a perfect fit in projects preparing the city for global exhibit, implying that traditional solidarism would be abandoned in favour of chasing after investment. The new urban coalition – the city government, real estate concerns, the bourgeoisie in its manifold manifestations, and the top echelons of the civil society, including the media and the city-boostering foundations funded by businessmen – strived to consolidate the city around their image of gentility.

The marketing of Istanbul proceeded along expected lines: the historical riches of the city as well as its night-life and culinary diversity were (and are) highlighted, along with dozens of music, art, and film festivals, new museums and exhibits. This, of course, was not a conflict-free process. The archaeological layers of the city’s many incarnations were alternative candidates for foregrounding.2 The Byzantine city, the Ottoman city of many cultures, or the imaginary Islamic city of the devout had to wage a battle with the Turkish city of the Republic. Since this last had too narrow a reference and obviously lacked marketing potential, what won out after a few years of competition was an inclusive Ottomanism, a re-imagined rubric encompassing the multifarious heritage of which the city could boast. The elite were happy to display their mansions and objets dating from the Empire; churches and synagogues were carefully restored along with mosques and the architecture of the everyday – apartment buildings and houses of the ordinary people. Ottoman art of the nineteenth century became a staple in the new museums where exhibits helped establish that the Ottoman elite had been very much engaged with European art, music, and literature. This was a new (and post-national) representation of the city in which the peripheral modernity of the Empire seamlessly flowed into an aspired status in contemporary global space. What it achieved was a narrative that could be easily appropriated by the global media, the art world, and taste makers who helped put Istanbul on the map – of investors, discerning tourists, curators of exhibits, real-estate developers, buyers of residences in ‘in’ cities of the world, and sundry consumers of culture.

I had written in 1999 that the city had embarked on the path to globalization but the process was haphazard and the results could best be termed ‘informal globalization’ (Keyder, 1999a). Istanbul’s success in this path, however, has become undeniable in the new century, and it is now grounded on solid institutional foundation. This should be attributed in large measure to the coincidence of political and economic expectations from the city, thus to the coherence of the urban coalitions which strived to upgrade the city’s image and marketing potential in the eyes of a footloose global demand – whether for investment, culture, or leisure. Since the mid-1990s, Istanbul has been governed by the same political party, and in fact by its leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan – first as mayor then as party leader and prime minister, but always hands-on where Istanbul was concerned. This is an unusual continuity given the political instability that characterized earlier periods. Especially after the national election in 2002 when Erdoğan became the prime minister, the central government allocated resources to upgrade the city’s infrastru...

Table of contents

- Planning, History and Environment Series

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- The Contributors

- Introduction: Orienting Istanbul – Cultural Capital of Europe?

- Part I. Paths to Globalization

- Part II. Heritage and Regeneration Debates

- Part III. The Mediatized City

- Part IV. Art in the City

- Part V. A European Capital?

- Index