- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mentalizing in Arts Therapies

About this book

This book describes the use of therapeutic art, music, and dance interventions against a background of mentalization, thus forging a link between arts therapies and mentalization-based treatment. This book has its roots in the theory of Mentalization Based Treatment by Antony Bateman and Peter Fonagy, and combines the broad experience of many art therapists with art, music and dance/movement therapy in psychiatric settings in the treatment of adults and adolescents both individually and in groups, as well as children with disorganised attachment. As a treatment concept, mentalization is quite straightforward because mentalizing is a typically human ability. As Bateman and Fonagy (2012) say: "Without mentalizing there can be no robust sense of self, no constructive social interaction, no mutuality in relationships, and no sense of personal security". On the other hand, it is not so simple to fully grasp the significance of mentalization. Mentalization-based therapy is a specific type of psychotherapy designed to help people reflect on their own thoughts and feelings and differentiate them from the perspectives of others.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

THEORY

CHAPTER ONE

What is mentalizing?

Mentalizing is a typically human capacity. It is something we do all day, every day. We often respond intuitively to the wide range of social exchanges around us. We see a facial expression or a posture and interpret it, depending in part on our own emotional state of mind at the time. We empathise and give meaning to the behaviour we see. In a sense, mentalizing is reading minds, feelings, and body language; it is largely nonverbal and implicit.

Bateman and Fonagy say that feeling understood stems from the experience of another person having your mind in mind, and much of this goes beyond words. They say that people can resolve interpersonal and intrapersonal problems by explicitly mentalizing about them—in other words, by dwelling on and reflecting on what both you and the other person think and feel about your relationship.

In Vermote and Kinet (2010) the Belgian authors Cluckers and Meurs give a clear example: “You’re not allowed to know what I’m going to do with that,” seven-year-old Sofie whispers to her therapist. “I know what it’s going to be, and you don’t!”…. “Guess!” (p. 11, translated for this edition).

In this exchange Sofie shows that she is aware she has thoughts and intentions that belong to her, that they are not automatically known to others, but that others can guess, ask about them, be curious or show an interest. In many of our clients, this awareness is far from self-evident. For them, their thoughts, fantasies, their feelings are not simply ideas; they are often part of reality as it happens to them, reality that can surely be seen and perceived by others. They make little distinction between external and internal reality and their own inner world, between their own mind and the mind of others. (p. 11, translated for this edition)

Mentalizing can be described as follows:

• Trying to understand yourself, another person, and your relationship by thinking about it.

• While you are arguing with someone, putting yourself in that other person’s shoes.

• Using the power of imagination to interpret human activity as based on intentions.

• Using understanding to perceive, experience, and observe the world around you.

• Empathising and giving meaning to mental content that determines your own behaviour as well as that of others.

• Thinking about what another person might mean, feel, or want and at the same time thinking about your own feelings, wants, or wishes.

• Seeing yourself as others see you and seeing others from the inside.

• Seeing through misunderstandings.

A Dutch-language training course provided by the Expertise Centre for MBT in the Netherlands, a partner in the worldwide network of the Anna Freud Centre (mbtnederland.nl), gave the following definition of mentalization:

The ability to perceive and understand your own behaviour and that of others in terms of intentional states of mind, such as feelings, thoughts, intentions, and desires. (Translated for this edition)

Why do some people have less capacity to mentalize?

In all of us, the capacity to mentalize changes from day to day, from moment to moment. Successful mentalization requires a balance between thinking and feeling. If you are overwhelmed by your feelings, or if you feel nothing, you cannot mentalize properly. To a certain extent, you must feel safe and secure in order to mentalize. If you are afraid, you will be preoccupied with protecting yourself and will be unable to take the time and trouble to mentalize.

You can even feel so panicked or angry that you cannot think clearly, let alone be aware of what another person thinks or feels. If you have had a huge fright, you may respond by scolding or railing against the other person without realising that he or she did not intend to frighten you. In such a case you are so agitated that you respond only to what you see, or think you see. Once you have calmed down, you usually realise that the other person meant no harm.

An iron that is too hot or too cool

The capacity to mentalize can be likened to an iron that is too hot or too cool. If you iron something and your iron is too hot, it will scorch. You stop mentalizing when you are in a highly emotional state: for example, when you are madly in love, or furiously angry. Then you are only capable of feeling, and you are unable to think about what you feel. You have to be able to think about your feelings in order to mentalize.

A state in which emotions run so high is a high arousal level, with increased stress and increased alertness. But if arousal levels are low—the other end of the scale—we cannot feel emotions properly. If your iron is too cool, it does not iron, leaving your garment still wrinkled. If you are depressed or listless, you will not mentalize. If the needs or feelings of others or yourself leave you cold, you will not want to mentalize.

You need to be able to feel what you are thinking and to think about what you are feeling in order to mentalize. If you find yourself in an argument with your loved ones and feelings flare up with great intensity, you will generally find it quite impossible to mentalize. It is at the times when you need it most, that mentalization is so difficult.

If problems are to be solved constructively, both parties need to bear in mind their own mental state and that of the other. The best way to get another person to mentalize is to do so yourself. Mentalization takes effort and motivation.

Rachel wants to work on the child in herself, whom she finds babyish and finicky. When this does not come up in our concluding discussion, she is angry with me and disappointed. The next week she talks about the clay figures she has made. The adult (Rachel) is exhausted and cannot lift herself off the ground; she cannot muster up the energy to look at the child. The clay does not show the babyish child who was discussed at the start of the session; she seems to have gone completely silent.

Illustration 1.1. The adult is exhausted and cannot bring herself to look at the child.

Rachel experienced the fact that her work was not discussed in the psychic equivalent mode: what she experienced externally and what she felt inside was the same. “I didn’t get a turn; Marianne (therapist) couldn’t even find the energy to look at me.” Her perception, reality, and her art work all seemed to momentarily coincide. The following week she is able to mentalize about the incident. She can leave behind the vehement emotion of the moment and think about her feelings: “I felt rejected. The whole situation seemed just like my clay figure, but time was up and the next group would come in any minute.”

This shows that the extent to which you are able to mentalize is always changing. The stronger your emotions, the harder it is to mentalize.

But you cannot mentalize all day long, and you should not. If you are in danger, you don’t stop to think about what you are feeling, you take action! Fortunately, this is usually second nature to us. If our stress levels are too high, our brain instinctively switches from the prefrontal cortical circuits, where the ability to mentalize is located, to the reflexive brain activity of the fight, flight, or freeze reflex. Hyperarousal and mentalization levels are like communicating vessels: when one increases, the other automatically decreases.

In addition to this natural reaction to a state of agitation, there can be another reason why a person is not able to mentalize properly. It is possible that the basis on which this capacity can best be developed was inadequate. Fonagy has demonstrated that the capacity to mentalize can only develop stably and well in a secure attachment relationship. Parents who are securely attached spontaneously adopt a mentalizing attitude towards their children. A complex interaction between the child’s genetic predisposition, parents who do not mentalize, and environmental factors is regarded as the most probable cause of a lessened capacity to mentalize.

Switch-point

An insecure attachment relationship can undermine the development of the capacity to mentalize, but this capacity can also be lost quickly when stress levels rise. People with a combination of early childhood trauma, insecure attachments, and certain genetic factors are at a disadvantage in their capacity to mentalize. When stress levels rise, the point at which the ability to mentalize is lost is much lower for them than for people without this vulnerability. When a child has been exposed to stressful situations for a long time, even a slight increase in arousal will cause his brain to switch to an automatic response. The switch-point at which the brain goes from controlled mentalization to an automatic reflex may have been permanently damaged.

Laura

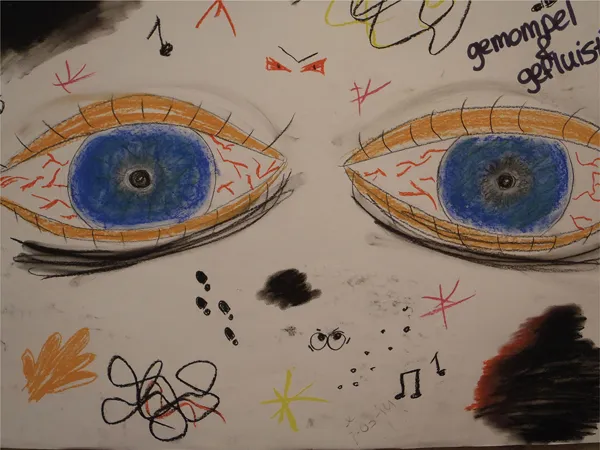

Hesitantly, Laura presents her collage to the group. It shows that she hears and sees things she knows are not there.

She talks about it during verbal group psychotherapy. In the individual art therapy that follows, I ask her how she thinks the others in the group see her now. Laura is pleased with their reactions and understanding, but she thinks that she is loopy. “What do you mean?” She explains: there are the real nutcases, then there are people who are obviously bonkers (like the ones who come to her mother’s house), and there is herself. She sees and hears things that are not real, and then you are really loopy; it’s scarier, because you can’t tell by looking at people that they have “it”. For her, too, it is scarier. I can follow her, and ask what she thinks about what goes on in her head. This is how she sees it: because she is very alert, she has a hard time falling asleep. This gets her brain mixed up and it sends out the wrong stimuli. But she doesn’t understand why it also happens when she is feeling well-rested. It reminds me of two of her art works, which show this watchful behaviour.

Illustration 1.2. Hearing and seeing things you know are not real.

I suggest that we take a closer look at these works, against the background of hearing and seeing things that are not real, in an attempt to make her implicit knowledge somewhat more explicit. We look at the fox who keeps one eye open to see whether anything is wrong. Laura made the fox to portray her interpretation of another person’s attitude towards her (see the opening section of Chapter Thirteen). Remarkably, she has symbolised only her own alert pose. In the other assignment, to depict the situation in the family in which she grew up in the form of a family boat, she draws a dilapidated pirate ship. On the stern she draws an armed pirate (Laura) protecting the captain (her mother), who is drunk, from a band of pirates (mother’s multiple partners) who are climbing on board and trying to enter the ship.

Illustration 1.3. The fox who keeps one eye open to see whether anything is wrong.

I tell her about the switch that changes position when danger threatens, and this leads us to discuss the automatic fight, flight, or freeze reflex.

Until recently, Laura fought and intervened in threatening situations. She does not do this in the group, because it would mean the end of her therapy. In the group, she either falls silent (the freeze response) or withdraws (flight). Yesterday her stress levels rose when two other members of the group had an argument, and they went down again when the nurses entered the room. She was very aware of this experience and realised that it meant that she trusted them! In the past, the youth care workers and the police just stood there and looked on, doing nothing, which confirmed to Laura that she had to watch over things herself.

I tell her that according to the theory, when children are exposed to high stress levels for a long time, the alarm goes off earlier and earlier and can even go off at times when ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- FOREWORD

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND CONTRIBUTORS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I: THEORY

- PART II: PRACTICE

- GLOSSARY

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Mentalizing in Arts Therapies by Marianne Verfaille in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.