This is a test

- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Body of the Organisation and its Health

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Using the frameworks of psychoanalysis, group relations, systemic organisational observation, consulting and research, this book explores the relationship between the health of the work force and the health of organisations. It seeks to do this through an exploration of experience that has three dimensions linked in a single matrix: The bodily, the emotional and the social. This exploration is inspired by Bion's original idea of the protomental matrix from which the group dynamics of basic assumption mentality are derived, leading to his initial ideas about group diseases and their cures.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Body of the Organisation and its Health by Richard Morgan-Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Chapter One

The body of the organisation and its health

The wounded surgeon plies the steel

That questions the distempered part;

Beneath the bleeding hands we feel

The sharp compassion of the healer’s art

Resolving the enigma of the fever chart.

That questions the distempered part;

Beneath the bleeding hands we feel

The sharp compassion of the healer’s art

Resolving the enigma of the fever chart.

East Coker from The Four Quartets, T.S. Eliot

I said to my, soul be still, and wait without hope

For hope would be hope of the wrong thing; wait without love

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith But the faith

and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

For hope would be hope of the wrong thing; wait without love

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith But the faith

and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

Burnt Norton from The Four Quartets, T.S. Eliot

The Collective Body:

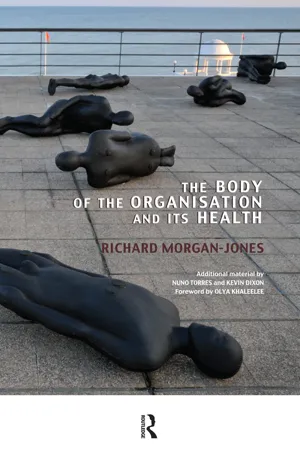

The body is the collective subjective and the only means to convey collective human experience perceived in a commonly understood way. Antony Gormley, sculptor, quoted in Antony Gormley, M. Caiger-Smith

Introduction

In this first chapter I am developing the metaphor of the organisational system as if it were a body. What I want to convey is the nature of engagement with the humanity of the enterprise, its spirit and its endeavour. This means that the chapter will move between different perspectives. I try to develop this metaphor and the role of human systems analyst, via examples from my own professional experience as it has unfolded. Each of these will try to indicate areas where addressing system failure is part of analysis and intervention, requiring the “sharp compassion of the healer’s art” (see Eliot quote above).

Use of metaphor of organisation as a body seeking health

“Community as Doctor” 1

The idea for this book has grown over the years and writing it has provided an opportunity to see if it is possible to clarify how the physical and emotional experience of the individual body connects to the experience of belonging to a group or an organisation. One dimension of this link is the human need for survival by social belonging. As the introduction to Part One suggested, never has this been a more pertinent issue when we as a human group have risked our own survival by putting our planet at risk. But another dimension of the social-body link is that the experience of belonging provides a vehicle for vitality, a sense of feeling alive with the possibility of an identity recognised by the group. The conflict between forces of life and vitality and forces of death and destruction can be explored at global, political, social, inter-personal, and intra-psychic levels.

My initiation into awareness of these issues occurred when I was 16 at a boys’ school where, for over a year, I was a member of a weekly Tavistock experiential group. This year-long group opened up the possibility of using language to describe experience and emotion. This learning eventually started a career, even though it took some years to crystallise.2 The weekly group was for me hugely therapeutic in the sense that I learned to “wait without hope”3 as experience emerged out of the unconscious world of the group process and we students learned to describe to each other deeply felt experience of relationships in families, to each other, to our gender identity as young men, and to our institution and culture more generally.

This experience left me searching for further group experience, so during a gap year before university, I was fortunate to secure a six month post as a social therapist at the Henderson Hospital. This was a Therapeutic Community in the Health Service, which used group and community therapy, treating patients with psychopathic personality disorders. There, patients who had been the despair of the prison, probation, and mental health services were invited to participate actively in their own therapy. They were helped to give voice to their impulses and feelings in groups, rather than acting them out in ways that had been dramatic, destructive, and without feeling. I learnt that in groups, irrational impulses can be brought under self-control by being talked through, even in those who appear least responsible for their actions.

At the age of 19 this was a baptism by fire into the world of therapeutic work. The daily dose of violence, passion, pain, tragedy, confrontation, and group dynamics opened me to experiences from which I still learn. Professional work was achieved by staff focusing on the dynamics and therapeutic norms of the unit. These were clearly spelt out in a research study that social anthropologist Robert Rapoport conducted under the title “Community as Doctor” (1960). It was this study and its title that had first attracted me to discover more about the hospital. It also drew me to the methodology of social anthropology of participant observation (Morgan-Jones, 1993).

The principles involved in the therapeutic community were clearly articulated ideas in the mind of staff and patients alike and constantly referred to as norms for relating in groups. These were to:

- Create a self-managing community in a hospital psychiatric unit by involving members lacking in social responsibility in the management and day-to-day running of the unit.

- Democratise the unit in the sense that all decisions, from admission to rehabilitation in the wider community, were subject to the views and interpretations of both members and staff.

- Deploy staff to ensure the boundaries of the programme were worked within and to be available for interpretation of here-andnow experience.

- Reflect on experience as a means of psychotherapeutic treatment in doctors’ groups run by a psychiatrist,4 in ward groups run by nursing staff, in work groups, and in the daily large group community meeting.

- In sum, all these principles facilitated the idea and practice of health and healing to be found in the inter-personal and intergroup processes of a psychiatric unit, geared to the twin tasks of treatment and rehabilitation.

Health in this context can be seen in the quality of inter-relationship between the different parts of the articulating organisational body—hence the book title “Community as Doctor”. Each and every relationship, activity, and process was available for commentary and reflection. The community as a whole was held together by its principles and the skill of staff and patients alike in engaging in the therapeutic task, inspired by psychoanalysis, that feelings and experiences need expression, not impulsive acting out in a way that might do material damage to the body and soul of perpetrator and victim.

I now want to illustrate the theme of this chapter with an illustration of health, conceived as: experience of the body seeking recognition and meaning.

Illustration: The body seeking recognition and meaning

Working in a social education project in the early 1970s, attached to Coventry Cathedral, I was part of a team running three or four day courses for groups of young people and those in their early 20s. The team specialised in social experiments with encounters between groups from very different backgrounds. The idea was that one group might, by its encounter with the other, provide a mirror to reflect un-thought experiences that could be shared and articulated. A theological college chaplain had paired up with the chaplain of a young offenders’ institution (a Borstal) to run an event for a group from both institutions. Our educational philosophy was based on a very simple three stage approach to creating opportunities for learning from experience:

- Send people out on a visit.

- Tell them they had to offer or give something and to receive something in the form of an activity, a gift, or a shared experience of relating.

- Create a setting where they could reflect on the experience in a group situation making observations on each other and those they met.

This approach was not far from Harold Bridger’s dual task approach (2001) to experience based learning, although I had not come across it at that stage.

When the chaplains and colleague staff met us for a planning meeting, the theme that emerged as relevant to both institutions was the experience and meaning of the body. The young offenders came from families marked by neglect, abuse, sexualised swearing, and violence that they had often recycled in crimes against the bodies of others. They had to suffer the institutionalisation of a celibate life in sexual frustration as part of their punishment for crimes within a culture where the vocabulary was strewn with bodily and sexual words and forms of aggression.

The theological students were exploring the Christian belief that in Christ the “word of God” was made flesh. Like the young offenders, they too lived in a somewhat celibate context, where encouragement to sublimate awareness of bodily experience into the spirit and the mind was ritually expressed in study and worship. For them the body was turned into a metaphor in a way that rendered sexuality unconscious. In exploring these two apparently different institutional cultures there were overlaps as well as differences. If the Borstal institutional culture over-stressed the body, often aggressively at the expense of others, the college appeared to avoid it. Crimes created secure accommodation and loss of liberty in a prison regime and theological students submitted themselves to the dependent security of obedience to study and ritual worship. One expressed aggression actively, the other passively with all the possibilities of alienating sado-masochistic relating.

It is worth noting that the Christian vision of the relationship between Christ and the body of the Church is compared to the relationship between a bride-groom and his bride. Further, one expression of Church membership—to some the most significant—is partaking in the communion service or mass where individuals receive and eat specially blessed bread with Christ’s words: “This is my body”. Nowhere is the relation between bodily experience and membership of the group so clearly articulated in the Western world as in the Christian teaching on incarnation and the doctrine of the Church as a body with membership.

As part of the design of their programme we paired people up from the two institutions and sent them in three different directions. One set of pairs went to visit people in the orthopaedic ward of a general hospital to find out what had caused the injuries to their bodies. Another went to a local school that specialised in children who were thalidomide victims, born with deformed or rudimentary limbs, with the task of organising a series of football matches with different groups. The third group of pairs went to the local crematorium to witness a funeral and to see behind the scenes what the process of disposal of the body entailed.

In the review, eyes had been opened to new dimensions of the body that had perhaps been known but not thought about (Bollas, 1999). One theological student reported that his Borstal partner had surprised him with his pastoral skills by making a “boys talk” relationship with a smashed-up teenage motor-cyclist. They had compared how to survive in a prison rather than a hospital with sexual frustrations. The budding priest had never thought of a pastoral conversation discussing the risk of shame in being discovered with a sticky handkerchief under the pillow!

One pair made common cause at the crematorium arguing that burning bodies behind the scenes was an inhuman indignity that others inflicted on the unknowing relatives through empty ritual. Later, friends in the reflective discussion pointed out that one was being trained to preside over such occasions and the other had been convicted of grievous bodily harm after a drunken fight put someone in intensive care fighting for his life.

One pair of the football “coaches”—again from both institutions—at the special school was bowled over by the courage and determination of the kids to play football using their various prosthetic limbs, carriages, cycles, and vehicles. They both asked for the possibility of a lon...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- INTRODUCTION Foundation stones to keep body and soul together

- PART I

- PART II

- REFERENCES

- INDEX