1 New relationships for old

‘She who has a hammer sees only a world of mails.’

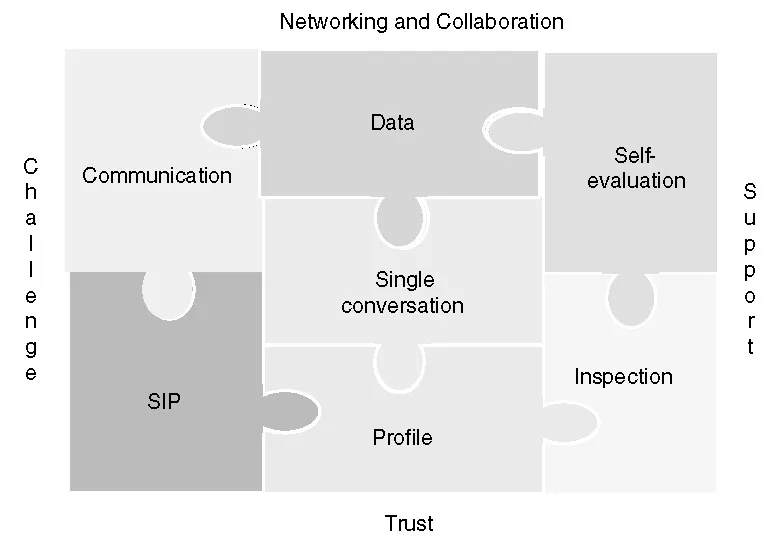

This opening chapter sets the scene for the New Relationship with Schools, (NRwS), examining the perceived need for a new relationship in light of what had gone before. Each of the seven elements of the NRwS jigsaw are examined in turn, arguing that schools need to view these with a critical and enlightened eye.

There is a new relationship between government and schools. It is an implicit recognition that the old relationship had been damaged by a decade of tensions and antagonism between agencies of government and schools. The legacy of the Thatcher regime, which cast teachers and ‘progressive educators’ as the enemy within, was little attenuated under a Labour government which did not want to be seen as soft on teachers. The retention of Ofsted and its Chief Inspector were a signal to teachers, but primarily to a wider public, that this administration too could be tough. After nearly a decade in power it became increasingly apparent that the old relationship was no longer sustainable and that it was time for a new approach.

The concept of a new relationship was first spelled out by the Government Minister, David Miliband in a high-profile policy speech on 8 January 2004.

There are three key aspects to a new relationship with schools. An accountability framework, which puts a premium on ensuring effective and ongoing self-evaluation in every school combined with more focussed external inspection, linked closely to the improvement cycle of the school. A simplified school improvement process, where every school uses robust self evaluation to drive improvement, informed by a single annual conversation with a school improvement partner to debate and advise on targets, priorities and support. And improved information and data management between schools, government bodies and parents with information ‘collected once, used many times’.

The New Relationship, elaborated in subsequent documents, promised to allow schools greater freedom, to free them to define clearer priorities for themselves, get rid of bureaucratic clutter and build better links with parents. Advances in technology promised improved data collection and streamlined communication. A School Improvement Partner, described as a ‘critical friend’ would liaise with schools and support them in achieving greater autonomy, releasing local initiative and energy. The seven elements of the new relationship were portrayed as an interlocking set, framed by trust, support, networking and challenge (Figure 1.1).

It is not hard to imagine hours spent in offices of government, redrafting and refining images and terminology to achieve the right register and to convey a genuine conviction that things could be different. While it is important to welcome the apparent goodwill and the government’s desire to build bridges, it is important to understand the political and economic context in which that relationship is set. On the economic front its main driver is the imperative to reduce public spending. Drastic reduction in the Ofsted budget, spelt out in the Gershon Report1 specified the need for ‘light touch inspection’, as much a concomitant of reduced funding as an argument for ‘grown up’ quality assurance. The political driver, closely allied to economic policy and New Labour’s embrace of the internal market2, required funding to be pushed down to front line services, accompanied by consumer choice and institutional accountability.

The good ideas inherent in the New Relationship, symbolised in the interlocking pieces in the jig saw need therefore to be examined with a critical and enlightened eye.

Elements of the New Relationship with schools

Self-evaluation

Prior to the election of New Labour in 1997 the Conservative government and its Chief Inspector of Schools rejected self-evaluation as a soft option which, it was claimed, had done nothing in its previous incarnations to raise standards. The 1997 election of a Labour government was a watershed for self-evaluation as, over the following years, it moved gradually but progressively towards centre stage. With the coming of a new Chief Inspector, David Bell, it was given a new status at the very heart of the new relationship. The key difference in this reborn self-evaluation was its liberation from an Ofsted pre-determined template, schools now being encouraged to use their own approaches to self-evaluation with the self-evaluation form (the SEF) serving simply as an internal summary and basis for external inspection. That at least, is the theory.

In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.

In theory self-evaluation allows schools to speak for themselves, to determine what is important, what should be measured and how their story should be told. In theory self-evaluation is ongoing, embedded in the day-to-day work of classroom and school, formative in character, honest in its assessment of strengths and weakness, rigorous in its concern for evidence. The New Relationship explicitly accepts these tenets and advises schools to adopt and adapt their own approach.

Figure 1.1 The seven elements of the new relationship.

In practice it is a different story. A recent study for the National College of School Leadership (NCSL)3 asked schools to describe the framework or model currently used in their school. The predominant response was simply ‘Ofsted’, ‘the SEF’ or its predecessor the S4. Asked for reasons for their choice the following was fairly typical. ‘We use Ofsted because we will be inspected and need to be prepared for that.’

While it was equally common for schools to say they used a combination of local authority guidelines and the Ofsted framework, the NCSL survey revealed that these are now closely matched to Ofsted protocols. Previous research by NFER4 in 2001 surveying 16 schools in 9 LEAs reported that 10 were using a local authority model, 4 were using the Ofsted framework while others used a ‘pick and mix’ approach, in one case Ofsted, plus Investors in People plus Schools Must Speak for Themselves. Since then the convergence between local authority models and Ofsted has gown stronger and the earlier more creative models tend to have been marginalised.

However strong the disclaimer by HMCI that the Ofsted SEF is not self-evaluation it is clear that self-evaluation is seen by the large majority of schools as a top-down form of review closely aligned with the criteria and forms of reporting defined by the inspectorate. Faced with an array of consultant leaders, LA advisers, school improvement partners and governing bodies all urging conformity to the SEF, it is only a brave, and perhaps reckless, headteacher who would not play safe. The availability of on-line completion of the SEF is a further impetus to see self-evaluation as forms to be filled and an event to be undertaken rather than a continuing process of reflection and renewal.

Inspection

The new inspection process takes the SEF as its starting point, so allowing a shorter and sharper process, given that schools have laid the groundwork and provided the Ofsted team with a comprehensive, rounded and succinct picture of their quality and effectiveness, strengths and weaknesses, allegedly warts and all. The main features of the new inspections are described in NRwS in the following terms:

- shorter, sharper inspections that take no more than two days in a school and concentrate on closer interaction with senior managers in the school, taking self-evaluation evidence as the starting point;

- shorter notice of inspections to avoid schools carrying out unnecessary pre-inspection preparation and to reduce the levels of stress often associated with an inspection. Shorter notice should help inspectors to see schools as they really are;

- smaller inspection teams with a greater number of inspections led by one of HMI. Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector will publish and be responsible for all reports;

- more frequent inspections, with the maximum period between inspections reduced from six years to three years, though occurring more frequently for schools causing concern;

- more emphasis placed on the school’s own self-evaluation evidence as the starting point for inspection and for schools’ internal planning, and as the route to securing regular input and feedback from users – pupils, their parents and the community – in the school’s development. Schools are strongly encouraged to update their self-evaluation form on an annual basis;

- a common set of characteristics to inspection in schools and colleges of education from early childhood to the age of 19;

- a simplification of the categorisation of schools causing concern, retaining the current approach to schools that need special measures but removing the categorisations of ‘serious weakness’ and ‘inadequate sixth form’, replacing them with a new single category of ‘Improvement Notice’.

‘Shorter’, ‘sharper’, ‘smaller’ are key downsizing elements of the new inspection. ‘Shorter’ applies to less notice so that schools may be seen ‘as they really are’, while a short stay in the school is premised on the school having ‘hard’ evidence of its practice, not preparing for inspection but always prepared. While it may easily be assumed from this that the purpose of the new inspection is to validate the school’s own self-evaluation, Ofsted is quick to disabuse people of that notion. While self-evaluation is described as an integral element of the process, inspectors will continue to arrive at their own overall assessment of the effectiveness and efficiency of the school. They reserve their judgement on the capacity of the school to make improvements, taking into account its ability to assess accurately the quality of its own provision. ‘Taking into account’ is an important caveat as it signals clearly the nature of the relationship between the external and the internal team. There is no pretence that this is an equal partnership.

Every Child Matters

A key constituent of the new relationship takes account of the five outcomes for children and young people defined in the policy document Every Child Matters.5 These are:

- staying healthy

- enjoying and achieving

- keeping safe

- contributing to the community

- social and economic well-being.

In judging leadership and management and the overall effectiveness of a school, inspectors examine the contribution made to all five outcomes. Claims made for validity and objectivity have, however, to be open to question given the breadth and ambition of the issues addressed. The highly subjective and sensitive nature of enjoyment, personal growth, parent and community links and equality belie any bold claims to objectivity and quantifiable ‘outcomes’. While now deeply internalised in the linguistic canon of school improvement, outcomes in relation to these five areas of growth seems singularly inappropriate.

Undaunted by complexity and subtlety inspectors are required to quantify their judgements on the following four-point scale, while schools are enjoined to do likewise.

| Grade 1 | Outstanding |

| Grade 2 | Good |

| Grade 3 | Satisfactory |

| Grade 4 | Inadequate |

These rest on very broad and, to a large degree, impressionistic judgements. They are necessarily selective as to evidence that can be found and can be measured. It is open to question whether these labels enhance or diminish the nature of the judgements made. While their virtue is simplicity, their weakness is the gloss which undermines the nuance and complexity of what is being e...