eBook - ePub

Writing Science Right

Strategies for Teaching Scientific and Technical Writing

This is a test

- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Writing Science Right

Strategies for Teaching Scientific and Technical Writing

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Help your students improve their science understanding and communicate their knowledge more effectively. Writing Science Right shows you the best ways to teach content-area writing so that students can share their learning and discoveries through informal and formal writing assignments and oral presentations.

You'll teach students how to…

-

- identify their audience and an appropriate organizational structure for their writing;

-

- achieve a readable style by knowing the reader's background knowledge;

-

- build effective sentences and concise paragraphs;

-

- prepare and deliver oral presentations that bring content to life;

-

- use major science articles, abstracts, and summaries as mentor texts;

-

- and more!

Throughout the book, you'll find a wide variety of sample articles and suggested assignments that you can use immediately. In addition, a list of additional teaching texts and resources is available on the Routledge website at www.routledge.com/9781138302679.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Writing Science Right by Sue Neuen, Elizabeth Tebeaux in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Educación general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Writing for the Readers: Know Your Audience and Analyze Their Needs

What Is Writing Science Anyway?

Writing science—to explain, describe, argue for or against scientific ideas—differs from other writing students have done in school. All of us learn to write by writing to our teachers. Our goal: to get a good grade, which we hope shows that we understand the material that has been presented. However, as we begin to study science and do so with more depth, we have to recognize that if we Write Science Right, we have to learn to write to a variety of readers, depending on the purpose we have in writing and the knowledge level of our audience.

The foundation of writing science and any technical writing is knowing how to write for its readers. This chapter will explain how to help your students design basic reports for various readers.

To begin:

- Readers must understand the meaning of what is written exactly as the writer intended.

- Writing must achieve its goal with the reader.

- Writers must create and maintain a positive relationship with their readers.

Questions for students to ask themselves about their readers:

- Who will read what I write?

- How much do they know about my topic?

- What is their educational background?

- Will they be interested in what I write?

- Why am I writing? What do I want them to know or do from what I have written?

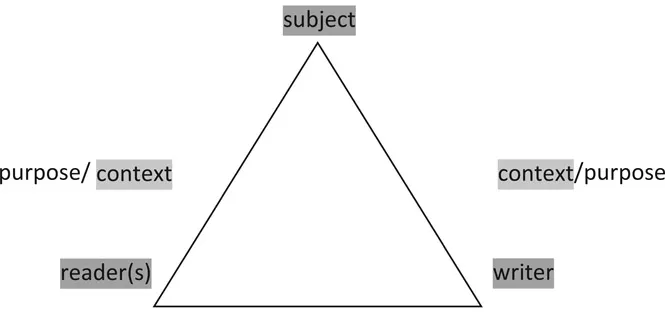

All writing is not the same and differs based on readers, purpose, context, and the subject.

Figure 1.1

All communication occurs in a context, the area outside the triangle in Figure 1.1. The subject, purpose, writer, and readers occur as a result of the context—what is occurring that makes the communication necessary. The emphasis and relationship among the three will determine the communication type.

For example, in science writing, the writer wants to create a relationship between the subject and the reader(s). The writer must attempt to bring the readers to the subject by knowing the readers’ needs and the intended goal for writing.

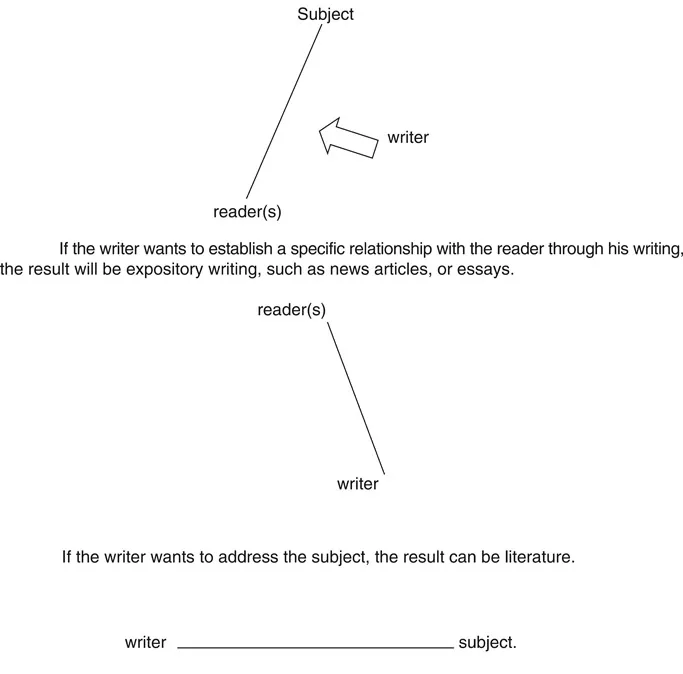

Communication forms assume their character depending on the relationships established around the communication triangle between the writer, the reader, and the subject.

Figure 1.2

Helping Students Create and Organize Their Writing

- Collecting and Grouping Information

- Planning Content Development According to Four Reader-Friendly Text Patterns:

- Topical Arrangement

- Reports Designed for Specific Reader Needs

- Chronological Arrangement

- Persuasive Argument Arrangement

- Strategies for Developing Content

- Partitions

- Definitions

- Questions

- Headings

When developing a report, first be sure students know the subject. They should not just begin writing! During the process of collecting information from research, interviews, and assimilation of material about the topic, have them think about how to organize the information collected: ways to arrange the ideas, where to place material within specific sections, how to decide “what goes where.” Considering arrangement of content during planning helps generate content in collecting information.

Organization is the heart and soul of effective writing.

Collecting and Grouping Information

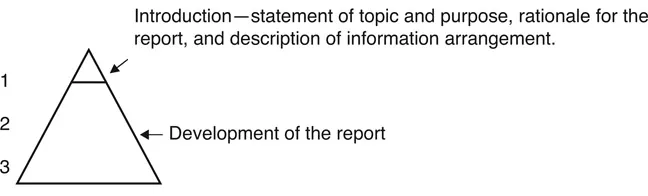

During research for information, have your students try grouping material and notes into specific categories. Have them label the categories. Next, instruct them to consider developing the report around main sections—the introduction and then information categories ordered in terms of the report purpose and reader needs. For long reports, students should consider having a file for each section, starting with the introduction.

Introduction

State the purpose of the report—what the report expects to accomplish and what reader(s) should learn. Any additional information can be included later. Stating the report purpose at the beginning of the draft helps students stay focused and tells reader(s) what to expect. Students can initially write down a list of the categories or topics that will be covered to achieve the purpose of the report:

- Category/topic 1: phrase describing the issue you want to present

- Category/topic 2: etc.

- Category/topic 3: etc.

Figure 1.3

After your students have determined the report information categories, they can begin inserting information under each topic or subject category. Initially, they insert information under the appropriate general topic. They can combine, revise, and delete ideas later. Examine the three paragraphs taken from James Watson’s DNA: The Secret of Life, Example 1.1. Watson carefully designs these paragraphs to help readers follow the DNA story. Note how Watson begins with a direct topic sentence (underlined), and then he develops support for the topic sentence. The more complex the concept is, the more important it is to carefully develop and organize the paragraphs to allow readers to follow the author’s main idea.

Notice how Watson uses examples to explain DNA in this first paragraph. As we will show, examples, description, and cause/effect provide just a few of the ways to explain concepts.

Example 1.1: Organizing Information Under Topics

¶ 1. The human body is bewilderingly complex. Traditionally, biologists have focused on one small part and tried to understand it in detail. This basic approach did not change with the advent of molecular biology. Scientists for the most part still specialize on one gene or on the genes involved in one biochemical pathway. But the parts of any machine do not operate independently. If I were to study the carburetor of my car engine, even in exquisite detail, I would still have no idea about the overall function of the engine, much less the entire car. To understand what an engine is for, and how it works, I’d need to study the whole thing—I’d need to place the carburetor in context, as one functioning part among many. The same is true of genes. To understand the genetic processes underpinning life, we need more than a detailed knowledge of particular genes or pathways; we need to place that knowledge in the context of the entire system—the genome.

(165)

In the second paragraph, Watson uses amplification to give readers a sense of the size of DNA.

¶ 2. The genome is the entire set of genetic instructions in the nucleus of every cell. (In fact, each cell contains two genomes, one derived from each parent: the two copies of each chromosome we inherit furnish us with two copies of each gene, and therefore two copies of the genome.) Genome sizes vary from species to species. From measurement of the amount of DNA in a single cell, we have been able to estimate that the human genome—half the DNA contents of a single nucleus—contains some 3.1 billion base pairs: 3,1000,000,000 As, Ts, Gs, and Cs.

In paragraph 3, Watson provides more examples, this time describing some of the ways genes affect our human lives.

¶ 3. Above all, the human genome contains the key to our humanity. Genes figure in our every success and woe, even the ultimate one: they are implicated to some extent in all causes of mortality except accidents. In the most obvious cases, diseases like cystic fibrosis and Tay-Sachs are caused directly by mutations. But many other genes have work just as deadly, if more oblique, influencing our susceptibility to common killers like cancer and heart disease, both of which may run in families. Even our response to infectious diseases like measles and the common cold has a genetic component since the immune system is governed by our DNA. And aging is largely a genetic phenomenon as well: the effects we associate with getting older are to some extent a reflection of the lifelong accumulation of mutations in our genes. Thus, if we are to understand fully, and ultimately come to grips with, these life-or-death genetic factors, we must have a complete inventory of all genetic players in the human body.

By organizing information, students can watch ideas gro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- eResources

- Meet the Authors

- Preface

- 1 Writing for the Readers: Know Your Audience and Analyze Their Needs

- 2 Achieving a Readable Style: Learn Techniques for Clear, Concise, Active Writing

- 3 Reporting Research Findings: Explore the Use of Science Articles and Letters

- 4 Planning and Presenting Oral Presentations: Discover Ways to Grab, Inform, and Persuade an Audience

- 5 Communicating a Complex Issue: Examine the Impact of Major Science Articles, Abstracts, and Editorials

- Afterword