![]()

Part I

‘Conventional’ Property Crime

This opening part of the book covers what we describe as ‘conventional’ forms of property crime: in essence, ‘volume’ offences which are prominent in official crime statistics and the investigation of which forms part of ‘bread-and-butter’ police work. Less frequently reported or researched forms of crime involving property, including ‘scams’, corporate and business crime, and state corruption, are covered in later sections. The use of the term ‘conventional’ also reflects the fact that the crime categories included in this part are closer to official and legal classifications than is the case with many of the other types of criminal behaviour discussed later.

The first three chapters deal with crimes against specific types of property: Maguire, Wright and Bennett focus on domestic burglary, Brown on vehicle crime, and Tilley on shoplifting. The fourth chapter by Sutton reviews what is known about a wide range of activities that are officially classified under the heading of ‘handling stolen goods’.

In combination, these four chapters provide many insights into modern forms of property crime. Maguire, Wright and Bennett reconsider, three decades after their original work on this topic, the current state of knowledge and thinking about domestic burglary. Since their research in the early 1980s, domestic burglary rates in England and Wales have more than doubled and then more than halved, and are now back roughly to where they started. Over that time, the nature of burglary has changed considerably, with new forms of the offence emerging, such as the growth in distraction burglaries (entry by trickery), car key burglaries (with the objective of car theft) and new forms of items being stolen (such as mobile phones). Moreover, the extent to which drug addiction acts as a motivating factor for burglary appears to have increased significantly. Extensive changes over time are also identified by Brown in his study of vehicle crime. Like burglary, car-related crime has seen a significant increase followed by a similar decrease. At the same time, there now exist more sophisticated methods of exporting vehicles and vehicle parts into Europe and beyond, while methods of enacting the theft have changed in response to changes in security technology.

By contrast, Tilley provides a trend curve for shoplifting which shows a gradual and sustained increase over time. However, he warns that official data are not good measures of shoplifting. The research evidence is also limited in that there is a strong correlation between the types of customers and types of shoplifters, both of which might change over time in response to changes in shops and shopping habits. Sutton has an equally difficult task in uncovering the characteristics of hidden markets in stolen goods. The kinds of goods traded reflect closely the types of goods that are fashionable and in demand.

The most striking theme that emerges from this collection of papers is that property crime is in itself innovative and changes in nature and form in response to broader social and cultural changes. It would appear that some of the most ‘conventional’ crimes that we might expect to know well from the past have in fact changed dramatically over the last two or three decades and may well continue to do so in the future.

![]()

Chapter 1

Domestic burglary

Mike Maguire, Richard Wright and Trevor Bennett

Background and definitions

‘Burglary’ in its modern guise in England and Wales is an offence defined under section 9 of the Theft Act 1968, which brought together under one umbrella the ancient offence of burglary (which referred only to forced entry into a dwelling by night with intent to commit a felony) with a variety of other offences which had accumulated over time, including house-breaking (which included entry in daylight), breaking into other kinds of building (shop-breaking, factory-breaking and so on) and non-forced entry into all kinds of building with intent to commit any of a number of named crimes. A person is now guilty of burglary under the above-mentioned Act if:

(1) (a) he enters any building or part of a building as a trespasser and with intent to commit any such offence as is mentioned in subsection (2) below; or (b) having entered any building or part of a building as a trespasser he steals or attempts to steal anything in the building or that part of it or inflicts or attempts to inflict on any person therein any grievous bodily harm

(2) The offences referred to in subsection 1(a) above are offences of stealing anything in the building or part of a building in question, of inflicting on any person therein any grievous bodily harm or raping any woman therein, and of doing unlawful damage to the building or anything therein.

In addition, a person is guilty of ‘aggravated burglary’ if he or she ‘commits any burglary and at the time has with him any firearm or imitation firearm, any weapon of offence, or any explosive’.

‘Burglary in a dwelling’ (also referred to as domestic burglary or residential burglary) is hence not a separate offence in law, although it is a Home Office classification used in the official recording and counting of criminal offences.

Burglary – and particularly residential burglary – has always been treated very seriously by legislators and the courts. Night-time forced entry into houses carried the death penalty until the early nineteenth century, and the current maximum penalty for burglary is 14 years, rising to life for aggravated burglary. There is also a minimum sentence of three years for a third burglary (unless there are exceptional circumstances) under the ‘three strikes and you’re out’ rule of the Crime (Sentences) Act 1997. As Chappell (1965: 3–9) argues, the origins of the severe penalties attached to burglary lie in the fact that it was attacks upon the security of a building or settlement – and hence of its occupants – rather than theft of the contents that the law was principally designed to punish. One of the earliest known definitions, recorded by Britton in about 1300, referred not only to housebreaking but also to the breaking of the walls or gates of cities. The emotional impact on victims of modern-day residential burglary can reflect similar anxieties about security, victims reporting fear, a sense of violation and no longer feeling safe in their own home; it is this, rather than the scale of financial loss, that motivates judges to continue to pass relatively heavy sentences on burglars.

This chapter presents a broad descriptive and (to a limited extent) explanatory overview of the offence and its perpetrators and victims, drawing on published statistics and a range of academic and government literature. It begins with a summary of trends in burglary rates over the past thirty or so years, together with an outline of common characteristics of the offence and the kinds of household most at risk. This is followed by a discussion of research findings on burglars’ perceptions of what they do and why, addressing questions about their general motives as well as their decision-making behaviour in specific circumstances. The chapter ends with a consideration of responses to burglary by various key actors: victims, police and other agencies concerned with crime prevention, and sentencers. The main focus is on domestic burglary in England and Wales, but evidence from the United States and elsewhere is also included.

Patterns and trends

In 2008/9 there were over 280,000 recorded offences of burglary in a dwelling in England and Wales (Walker et al. 2009). This represents 48 per cent of all burglaries (including commercial burglaries), 8 per cent of all property crimes, and 6 per cent of all recorded crimes. Domestic burglary ranked fifth in numbers of crimes recorded behind ‘other theft offences’ (approximately 1.1 million), criminal damage (940,000), vehicle crime (600,000) and burglary in a building other than a dwelling (300,000).

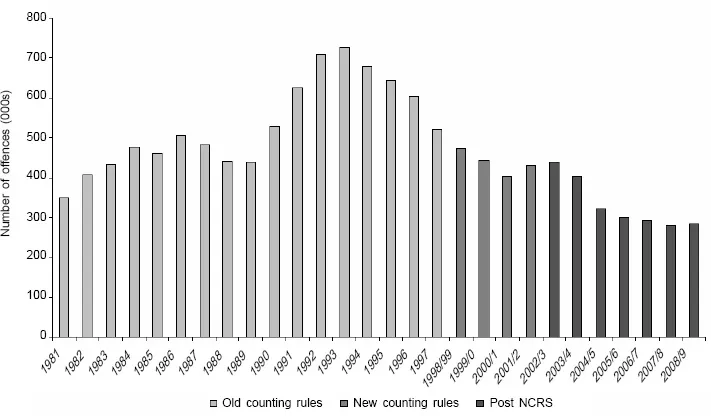

The long-term annual trends in police recorded ‘burglary dwelling’ show a gradual increase over the 1980s and a particularly steep rise in the early 1990s, but then a lengthy and sustained decrease from the peak in 1993 until 2007/8 (see Figure 1.1). This trend is largely mirrored in British Crime Survey (BCS) findings on reported domestic burglaries, which also show a peak in the mid-1990s, followed by a marked decline until the mid-2000s. Indeed, according to the BCS, the numbers of such offences have more than halved since 1995. Large falls have also been observed in several other western countries (Bernasco, 2009). However, there is some current concern in England and Wales that this trend may have come to an end. The Home Office Statistical Bulletin for 2008/9 showed that there had been an increase of 1 per cent in police recorded residential burglaries from the previous year, which represented the first annual increase in the offence since the introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard in 2002.1 BCS figures also rose marginally over the same period, as they had done in 2007/8. The media has seized upon such figures as evidence for the idea that property crimes, such as residential burglary, are likely to increase during a recession (Field 1990, 1999). However, the increase in both cases is modest, and whether it really marks a break in the long-term declining trend and the beginning of a recession-fuelled rise will not be known until further evidence becomes available.

Figure 1.1 Trends in police recorded domestic burglary, 1981 to 2008/9

Source: Walker et al. (2009).

Some significant variations in domestic burglary are apparent across different areas. As with many other types of volume crime, higher rates tend to be found in major cities than elsewhere. BCS figures for 2007/8 show that the rate of burglaries per household in London was 411 offences per 10,000 households, while in Wales it was only 226. At the same time, they indicate that, over the past few years, domestic burglaries have declined more rapidly in deprived areas than in more wealthy areas. For example, over the period 2001/2 to 2007/8, there was a reduction of 38 per cent in the 20 per cent most deprived areas, compared with one of only 9 per cent in the 20 per cent least deprived areas (Kershaw et al. 2008).

Characteristics of the offence

The regular Home Office statistical publications give few details about offences of domestic burglary. However, in 2007 a special Home Office analysis of BCS results was published which went some way towards addressing this omission (Kent 2007). In this section, we briefly summarise what is known from this document and elsewhere about the times at which burglaries are most likely to take place, how entry is most frequently made and the types of household most likely to be victimised. We also consider the extent to which burglaries are reported to the police.

According to the 2005/6 BCS (Kent 2007), burglaries were relatively uncommon in the mornings (8 per cent) but fairly evenly distributed during the rest of the day (24 per cent in the afternoon, 25 per cent in the evening and 25 per cent overnight). The front of the property was a more common entry point (48 per cent) than the back (40 per cent) or the side (9 per cent). Doors (70 per cent) were also more common entry points than windows (28 per cent). Although the majority of entries were forced, over a quarter of all reported cases involved entry through an unlocked door.

The 2007/8 BCS further shows that the median value of goods stolen in domestic burglaries was £360. The most common group of items stolen was ‘purse/wallet/money etc.’ (51 per cent of all reported burglaries in which entry was achieved), followed by ‘jewellery’ (29 per cent) and ‘electrical goods/cameras’ (24 per cent). Mobile phones have also become a target in a significant proportion of burglaries, rising from about one per cent in 1993 to almost 20 per cent in 2003/4, although since then falling back to around 15 per cent. By contrast, there has been a major reduction in a type of burglary that was common twenty or thirty years ago: cases involving theft of the cash contents of gas or electricity pre-payment meters. This phenomenon, which was often regarded cynically by police officers as ‘do-it-yourself’ crime by members of the household (Maguire and Bennett 1982), has virtually disappeared with the introduction of token systems and other non-cash payment methods.

Finally, apparent increases in two specific types of burglary have caused concern in recent years. One is ‘distraction burglary’, particularly when committed against older people. This is defined as gaining entry by ‘a falsehood, trick or distraction’ (Home Office 2003), and often involves offenders posing as officials to ‘talk their way’ into the house or to distract the victim’s attention in order to steal (Thornton et al. 2003). Estimates based on samples of police reports suggest that in 2003/4 distraction burglary accounted for 4 per cent of all recorded burglaries in England and Wales (Ruparel 2004). This is similar to a finding from the 2005/6 BCS that 5 per cent of burglaries involved entry by ‘false pretences’. The other phenomenon causing concern is ‘car key’ burglary, where the offender enters the house in order to steal the victim’s keys and drive off in their car. Recent police figures indicate that the numbers of such cases are rising, and in 2008/9 occurred in 7 per cent of domestic burglaries (Walker et al. 2009).

Victims and repeat victimisation

According to the BCS, the annual risk of an average household in England and Wales being a victim of burglary has been fairly stable over the last few years at around 2.5 per cent (Walker et al. 2009). However, this risk varies con...