![]()

![]()

Knowing Isn’t Everything

Have you ever made coffee in the morning on “autopilot” or drove to school without trying to remember how to get there? What about choosing what to have for lunch: how often do you really think about all of the options available? You don’t need to know what you are doing to get things done. You can tie your shoes without making bunny ears and read a book without sounding out each word. All of these thought processes are implicit, or unconscious. How did you decide to read this book (and if you have to read it for class or professional development, then why right now)? Perhaps you chose it from a list of books on implicit bias or saw a review you liked. Maybe you were assigned this book and realized that you had to read it now or you wouldn’t get the reading done in time. These kinds of thoughts are more explicit, or conscious. Implicit thoughts are those we don’t really think about and just do, while explicit ones are those where we consider options and often reason our way to conclusions.

This book is dedicated to the part of our cognition that is activated involuntarily and outside of our intentional control. By definition, implicit bias refers to stereotypes and attitudes that occur unconsciously and may or may not reflect our actual attitudes. Although unconscious, implicit biases can affect our perceptions, actions, and our decisions across realms ranging from the relatively trivial (e.g., recognizing that “green means go” on a stoplight) to those quite significant (e.g., in a school discipline situation, which student is perceived to be more or less culpable than another). This chapter begins the conversation to understand how – regardless of our explicit intentions – the unconscious part of our cognition can shape our actions and ultimately the outcomes that occur in educational environments.

Good Intentions Gone Wrong

– Anna Danylyuk

Education for ALL

The U.S. Department of Education claims to work toward this mission in two ways: by the secretary and department leading national dialogues on result improvement and by the administration of a variety of education-focused programs.

The desire for our education system to support every student along the pathway to success is embodied by the United States Department of Education’s mission to “promote student achievement and preparation for global competitiveness by fostering educational excellence and ensuring equal access” (U.S. Department of Education, 2011, p. 1). Schools need to equip all students – regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, or ability status – with the opportunities and skills necessary to reach their full potential. Despite these good intentions, achieving these aims is challenged by issues rooted in the educational system such as overworked teachers, extensive standardized testing, and paperwork that seems to never end. In addition to these pressures, person-to-person issues such as language barriers, children who have experienced trauma, and differences in cultural backgrounds may impede educators’ progress in developing relationships with their students. Outside of schools, even more factors can contribute to students’ success – family support, economic advantages, neighborhood dynamics – this list can go on and on. Taken together, schools are facing an uphill battle in the pursuit of equitable academic excellence access.

If we want to make schools a place that benefits all students, we must explore why our intention to provide educational opportunities falls short of producing equitable outcomes. A critical piece of this puzzle is the immense need to highlight the importance of students’ identities as a factor that can support or inhibit their academic and social-emotional development. A growing body of research on implicit bias (also called unconscious bias) demonstrates that aspects of an individual’s identity such as race, gender, or ability status are associated with a variety of stereotypes that can influence how others perceive or interact with that individual.

Don’t Sound the Alarms Yet!

While bias typically holds a negative connotation, bias is in actuality a neutral term. You might have a bias for summery weather or delicious food as opposed to an ice storm or sour milk. Not all biases are harmful and in some cases they can be quite helpful. Next time you avoid stepping on a wad of chewing gum, know your bias for clean ground is there to assist you.

Biased perceptions can unintentionally influence decision-making and actions outside of conscious awareness in ways that do not mirror our explicit commitment to equality (Greenwald et al., 2002; Kawakami & Miura, 2014). Often, these biases reflect stereotypes and patterns of marginalization in society rather than what we actually believe or feel. In acknowledging that implicit biases often run counter to the values that we – as educational leaders – hold, we begin to understand the nuances of how inequities can persist in the absence of overt discrimination. By revealing the nature and operation of implicit bias, the authors of this book hope to move readers toward becoming better practitioners, leaders, and people.

What Is at Stake?

The achievement gap refers to differences in the academic results (test scores, higher education, job attainment) between different groups of students – typically between students who are Black and students who are White. Similar terms include the opportunity gap, which refers to differences in resources and educational quality, the learning gap referring to differences between what students actually learn and what they are expected to learn, and the discipline gap referring to differences in how often students of different groups are suspended and expelled from schools. In all of these gaps, low socioeconomic status students and students of Color typically experience more detrimental outcomes (lower test scores, more suspensions) than White students.

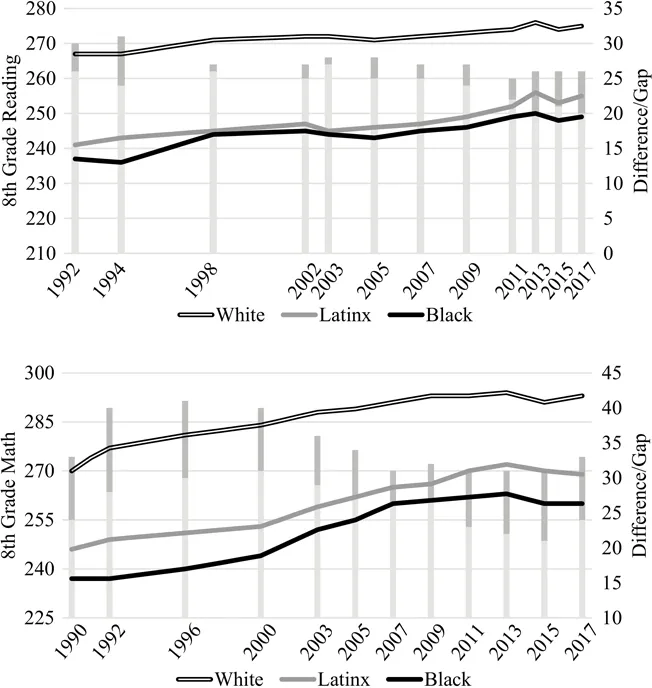

Our nation’s students depend on schools to uphold their commitment to educational excellence and equal access. When we fail to uphold this commitment to all students we encounter issues like the achievement gap between White and racial minority students – particularly Black and Latino students as compared with White students. While the achievement gap as a whole has narrowed in the past 50 years, notable progress has stalled. According to National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) data, the progress made to begin closing the achievement gap in the 1970s and 1980s reached a plateau by the early 1990s, since when it has remained relatively stable (Barton & Coley, 2010). Figure 1.1 shows the achievement gap since the early 1990s. Beyond the academic outcomes, racial disparities occur along the pathway to achievement including different levels of advanced course access for Black and Latino students as compared with White and Asian students (who have far greater access) – especially for math and science (Office for Civil Rights, 2016).

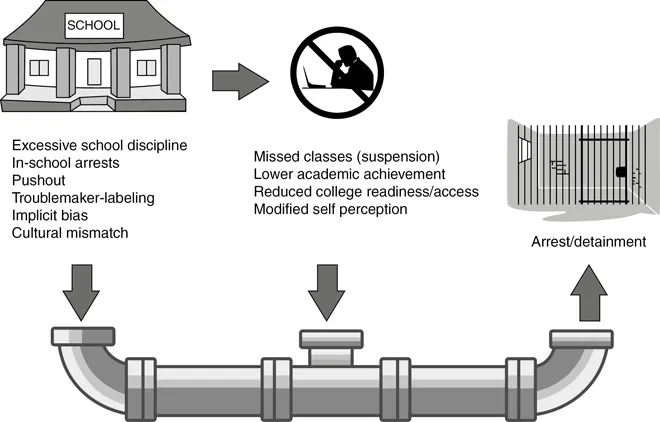

Academic achievement is only one, albeit large, piece of this puzzle. Punitive discipline use can limit students’ educational opportunities and even push students toward justice-system involvement – otherwise known as the school-to-prison pipeline, as illustrated in Figure 1.2. As Senator Dick Durbin (2012) described in an address to Congress on the school-to-prison pipeline, “For many young people, our schools are increasingly a gateway to the criminal justice system. What is especially concerning about this phenomenon is that it deprives our children of their fundamental right to an education” (p. 1). By calling attention to the culture of punitive discipline prevalent in public schools, Senator Durbin urged the committee representatives to consider the implications of school discipline practices and the role of race in disciplinary outcomes.

Researchers often explore links between the achievement gap and the discipline gap, considering that these gaps might be “two sides of the same coin” (Gregory, Skiba, & Noguera, 2010). Just as expected, disparities in school discipline are just as pronounced and pervasive as academic disparities (American Civil Liberties Union, 2008; Losen, Hodson, Keith, Morrison, & Belway, 2015; Office for Civil Rights, 2016). For example, the Office of Civil Rights’ analysis of 2013–2014 discipline data found Black students were 3.8 times more likely to receive an out-of-school suspension than White students (Office for Civil Rights, 2016). The data also revealed American Natives, Latinx, Pacific Islanders, and multiracial boys were disproportionately suspended, but to a lesser extent than Black boys. Other studies show drastic differences in days suspended by race for students with special needs, with Black students with disabilities receiving three times as many days of lost instruction as White students with disabilities (Losen, 2018). These examples are just small pieces of part of a large body of evidence showing disparities in school discipline that span across racial, gender, and ability identities. Together, these disparities in academic and discipline outcomes contribute to persistent racial differences in high school completion rates (Barton & Coley, 2010; Reeves, Rodrigue, & Kneebone, 2016).

As these disparities show, we still need to address the inequity in our education system. Before we provide you with the knowledge and tools you need to begin this process through implicit bias remediation, we must begin by considering the influence of our collective past. By examining the education system’s policies, practices, and historic barriers to achieving racial equity, we can better understand how implicit biases emerge and learn from previous successes and failures to improve educational trajectories for students of Color. Like other national institutions, the education system is part of a legacy of legally endorsed discrimination. Though a full retelling of this history is outside of the scope of this book, it is worth considering key points in our history that made a lasting imprint on the co...