![]()

1

Ecological living

There are two worldwide systems that we depend on for our existence. The first is the biosphere – all life on Earth. This is the extraordinarily complex web of extremely complex ecosystems, along with the planet’s soil, water, and air. We depend on this system for the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the food we eat. The second system is made up of the mines, wells, refineries, factories, warehouses, and shops that supply us with the many goods and services we’ve come to need and take for granted. This productive system includes the world’s farms and ranches, and also its ships, railroads, trucks, highways, etc. It might seem that we could get along without most of the productive system. Human beings did spend most of our existence with extremely simple production, in which everything was made by hand out of wood, bone, skins, and stones, and trade between groups was very limited. So we could live that way again, but probably only with the sorts of populations we had then – maybe 20 million for North America. Getting there would be unpleasant at best, and disastrous at worst. And while some people romanticize hunter-gatherer life, very few would really want to live that way. So we need both systems.

Unfortunately, however, there is a basic conflict between the two systems. The productive system seems to be dependent on extracting more and more resources from Earth and turning them into pollution that damages ecosystems. Perhaps the most harmful effects of our ever-growing production are the unprecedented extinction of species − which is rapidly reducing the diversity that the biosphere depends on – and climate change – which is disrupting the biosphere in many known and unknown ways. The productive system’s need for ever-increasing extraction of resources also means that it is running out of high-quality, easy to get resources and must use more energy, and do more harm, to get more materials out of low-grade, harder to get ores or deposits. This process is already obvious in the new techniques we’re using to extract fossil fuels – mountain top removal, deep water and arctic drilling, and tar sands and hydraulic fracturing (fracking). The combination of the need for more extraction each year and more harmful extraction methods means that the conflict between the two systems we depend on will only get worse, at least as long as the productive network continues to work as it has for the last two or three centuries.

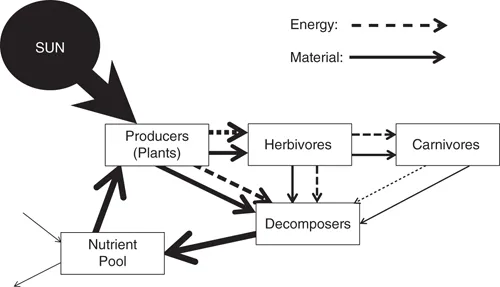

So, the most important question of our time is this: Can the two systems work well together, and if so, how? Is it possible to have thriving life on earth and at the same time supply people with at least the most important goods and services from our productive system? To even begin to answer these questions, we need to know more about these systems, networks, orders, or webs, or whatever you want to call them. The biosphere and its ecosystems are solar-powered recyclers of materials. Plants capture solar energy and turn basic materials into living matter that contains energy. This matter and energy go up the food chain until the energy is exhausted, and the materials are recycled to the soil. The energy has to be renewed constantly, but most of the materials are recycled again and again, as shown in Figure 1.1. This has allowed life on Earth to evolve, recover from disasters, and thrive for hundreds of millions of years.

Figure 1.1 A simplified diagram of energy and material flows in an ecosystem. Energy flow is one-way; material flow is cyclical. Fine arrows represent minor material flows into and out of the system.

(After Kormondy, 1969, p. 4)

The productive system has been called the extended order of human cooperation. It includes the networks of production and transportation, and also the political, legal, and financial systems that go with it. The extended order includes our laws, customs, and morals which evolved along with the rest of it. The extended order also includes concern for future generations, for the simple reason that societies that have had that concern tended to do better than those that did not. The extended order and the biosphere are similar in many ways. Both evolved. Both are far too complex to have been designed or created by one person or one group of people, and neither can be completely understood, directed, or controlled by a single person or group. Both thrive on diversity and consist of billions of individual agents, all pursuing their own goals and allowing each other to survive – often to thrive. Both free-market supporters and environmentalists believe that these complex evolved systems should not be interfered with; they just disagree on which one should be respected and which should be bent to our will.

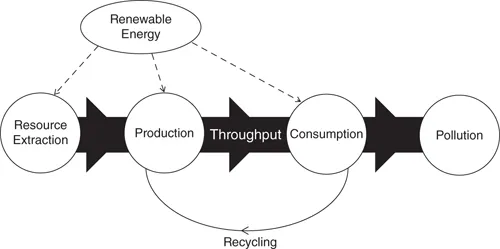

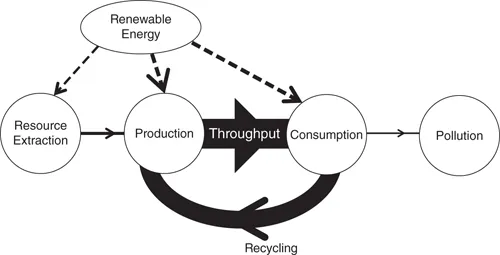

I will try to show that the two systems we depend on can work well together. To make that happen, the human extended order has to change from extracting more resources each year to extracting fewer. In order to do that, it must use resources less wastefully and must depend more and more on renewable energy and recycling instead of extraction. This means making the extended order work like the biosphere – making it a renewably powered recycler of materials, the only kind of world-scale system that can survive on Earth for long periods of time (see Figures 1.2 and 1.3). Having the biosphere and extended order work together – or at least moving in the direction of being able to do so – can be called ecological living. Although making the extended order develop in that way will be an unprecedented intervention in its working, I believe it can be guided in that direction by means that are consistent with its basic principles.

Figure 1.2 The way our productive systems work now. Throughput is high and growing in “normal” periods. Renewable energy use and recycling rates are low, so extraction, throughput, and pollution are approximately equal. Pollution includes GHGs from fossil fuels.

Figure 1.3 The way our productive systems will work in ecological living.

Reducing resource consumption while producing the same or more goods and services is called decoupling, and a lot of this book deals with questions about decoupling. Is it real? Could it allow continued economic growth with less resource extraction? Could it help to provide a decent standard of living for all the billions of people on Earth now and in the future? Could it allow a slowly growing or steady-state economy to get along with less extraction each year? If so, how long could that go on? Fortunately, every resource has a certain number of years left at the rate we’re extracting it, and there is a constant rate of decrease that will allow that resource to last forever. And it looks like decreasing extraction at these rates should be possible, which means that ecological living should be possible.

Global and local, large and small scale

This book focuses on the global scale – on world resources, extraction rates, standards of living, and population. Many people who are concerned with sustainability may believe that this is the wrong approach – that global schemes are necessarily destructive and that we have to focus on local production for local consumption. But many of the things that we depend on and take for granted can only be the products of a global system. Earth’s resources are very unevenly distributed, and all are required in each country’s economy. So international trade in resources is inevitable. As ecological living leads to less extraction and more recycling at the local level, the amounts of resources shipped around the world will decrease. Importing most of our consumer goods because they can be made with cheap labor somewhere else will decrease rapidly, as the incentives that will keep an economy in ecological living will also encourage more domestic manufacturing. Maybe in a century or two our technologies will have improved to the point where (almost) everything can be made locally out of (almost) entirely recycled materials, but until then we will continue to be dependent on the necessarily global extended order.

Ecological living will almost certainly involve a steady-state, or slowly growing, economy. It may even go through a period of economic de-growth as particularly wasteful consumption is eliminated. For this to work, societies will have to be much more economically equal than they are today, particularly in the United States. Extreme and increasing inequality is very harmful to most people – not just the poor – and should be reduced in any case. In a (near) steady state, the need for less inequality will be even stronger because economic growth will no longer be available as a substitute for equality.

It’s impossible to say how successful ecological living will be in terms of providing good standards of living. That will depend on what future technologies will be like and particularly on how effective decoupling will be at providing goods and services with less extraction. What is clear is that the sooner we begin the transition, the more remaining resources there will be, and the better our futures can be. If ecological living is done right, it should involve less production because goods will use fewer resources, and they will be more durable and recyclable. Combined with continuing automation, this would mean that less labor will be required. In a more equal society, this cannot mean more unemployment. It would mean that people will work less; work weeks will get shorter, and/or people will take longer vacations. As people have more free time, they’ll have the freedom to become what they want to be and to make ecological living what they want it to be.

The ideas behind ecological living can be considered a branch of environmentalism. They grew out of concern for the harm that our productive systems are doing to our planet. But unlike a lot of environmentalism, ecological living is not about doom, gloom, guilt, and doing without. Reducing some aspects of excess consumption and consumption for its own sake can be part of it, but it’s mainly a positive vision of a future in which people are more economically secure and have more freedom to grow and develop as they choose.

Reference

Kormondy, Edward J. (1969). Concepts of Ecology, Prentice Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

![]()

2

Ecological living, the steady state and sustainability

The ideas behind ecological living have a long history, perhaps starting with John Stuart Mill in 1857. Mill believed that economic growth must someday end in a “stationary state,” which “would be, on the whole, a very considerable improvement on our present condition” (1857). The first modern thoughts on the subject came from the economist Kenneth E. Boulding, who summed up the basic concept very well in 1966:

The closed earth of the future requires economic principles which are somewhat different from those of the open earth of the past. For the sake of picturesqueness, I am tempted to call the open economy the “cowboy economy,” the cowboy being symbolic of the illimitable plains and also associated with reckless, exploitative, romantic, and violent behavior, which is characteristic of open societies. The closed economy of the future might similarly be called the “spaceman” economy, in which the earth has become a single spaceship, without unlimited reservoirs of anything, either for extraction or for pollution, and in which, therefore, man must find his place in a cyclical ecological system which is capable of continuous reproduction of material form even though it cannot escape having inputs of energy.

The difference between the two types of economy becomes most apparent in the attitude towards consumption. In the cowboy economy, consumption is regarded as a good thing and production likewise; and the success of the economy is measured by the amount of the throughput from the “factors of production,” a part of which, at any rate, is extracted from the reservoirs of raw materials and noneconomic objects, and another part of which is output into the reservoirs of pollution. If there are infinite reservoirs from which material can be obtained and into which effluvia can be deposited, then the throughput is at least a plausible measure of the success of the economy.

[ … ]

By contrast, in the spaceman economy, throughput is by no means a desideratum, and is indeed to be regarded as something to be minimized rather than maximized. The essential measure of the success of the economy is not production and consumption at all, but the nature, extent, quality, and complexity of the total capital stock, including in this the state of the human bodies and minds included in the system. In the spaceman economy, what we are primari...