Types

A vessel’s transportation network may be an origin-to-destination (O-D), a mainline-feeder (MAIN-FEED) or a mainline-mainline (MAIN-MAIN) transportation network (Chadwin, Pope and Talley 1990). In an O-D network, the same vessel transports cargo from its origin port through the network to its destination port. In the MAIN-FEED and MAIN-MAIN networks, the same vessel does not necessarily transport cargo from its origin port to its destination port. These networks consist of sub-networks that are connected by a common port. For the MAIN-FEED network, the sub-networks consist of a mainline network over which cargo is transported in relatively large vessels and a feeder network over which relatively small vessels feed cargo to and from the mainline network via the connecting (or feeder) port. When cargo is transferred from one vessel to another at a given port, the cargo is referred to as transshipment cargo. The MAIN-MAIN network consists of two mainline networks, where cargo is transferred from one mainline network to another at a port that is common to both mainline networks. By contrast, an O-D network is one for which there is no transshipment of cargo among the network’s ports.

An O-D network may be a constant or a variable frequency port-call network. A constant frequency port-call network is one over which a vessel calls at all ports in the network the same number of times (generally once) on a given round trip. A variable frequency port-call network is one over which a vessel calls at some ports more than others on the same round trip.

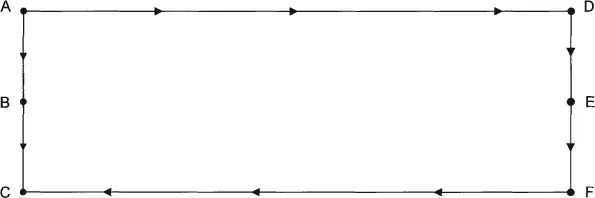

A constant frequency port-call O-D network is depicted in Figure 1.1. The figure has two separate ranges of ports separated by an ocean, with ports A, B and C on one side and ports D, E and F on the other side of the ocean. A vessel calls once at each port on each round trip, covering a broad range of ports. If the number of port calls on the network increases, vessel schedule adherence (and thus the reliability of service) is likely to be adversely affected.

Figure 1.1 Constant frequency port-call O-D network

A variable frequency port-call O-D network is depicted in Figure 1.2. It depicts the network in Figure 1.1 except a vessel calls at port A twice while maintaining one call at each of the remaining ports on each round trip. A broad coverage of ports is maintained on a variable frequency port-call O-D network, while providing more frequent vessel calls at ports where there are higher volumes of cargo.

Figure 1.2 Variable frequency port-call O-D network

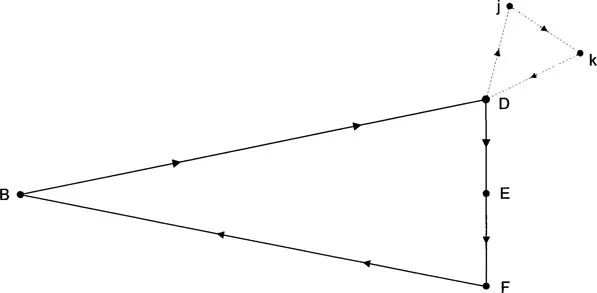

Figure 1.3 Mainline-feeder network

A mainline-feeder network is depicted in Figure 1.3. The mainline network DEFB has a connecting feeder network Djk, feeding cargo into and out of feeder port D, a port common to both networks. Relatively large vessels serve mainline network DEFB and relatively small vessels operate over feeder network Djk. The vessel service achieves broad coverage in the DEF port range, takes advantage of a vessel’s cost economies of vessel size at sea by calling at only one port on the ABC port range and takes advantage of a vessel’s cost economies of vessel utilization (or load factor) in port from the increase in the concentration of cargo at port D.1

Cost savings to the shipping line in the network in Figure 1.3 are expected to arise from feeder-ing cargo on a relatively small vessel from port j to port D and then combining this cargo with cargo already at port D for transport on a relatively large vessel to destination port B – as opposed to providing direct service between ports j and B and between ports D and B. However, with this cost savings, a loss in revenue to the shipping line is also expected. Feeder vessel service generally is a poorer quality of service than direct vessel service. For example, the sum of the transit times of cargo moving from port j to port D and then to port B will be greater than the transit time of direct service between ports j and B. If the shipping line seeks to maximize profits, it will have been rational in establishing a feeder port at port D if the cost savings related to the feeder port are greater than the revenue lost.

In Figure 1.4, a mainline-mainline network is depicted, consisting of mainline networks ABCE and GHIE, having the common port E. At port E, cargo is transferred to and from the two networks from one vessel to another. Since relatively large vessels are used on mainline networks, the vessel service is able to take advantage of cost economies of vessel size (i.e., utilizing a larger vessel) at sea. The shipping line will have been rational in establishing a transshipment port at port E if the cost savings related to the transshipment port are greater than the revenue lost. In Figure 1.5, a combination of mainline-feeder and mainline-mainline networks has been created by merging the networks depicted in Figures 1.3 and 1.4.2

Vessel service patterns

Figure 1.4 Mainline-mainline network

In sailing over vessel transportation networks, vessels may use a number of service patterns, for example, end-to-end, round-the world, pendulum, triangle and double-dipping service patterns (Tran and Hans-Dietgrich 2015, p. 145). In an end-to-end vessel service pattern, a vessel sails back and forth between two markets, say the West Coast of North America and the Far East markets. In a round-the-world vessel service pattern, a vessel sails in only one direction, say westbound or eastbound. In a pendulum vessel service pattern, a vessel sails among three markets and the middle market is the service’s fulcrum, where a vessel swings to its either side in order to service the three markets. In the triangle vessel service pattern, a vessel serves three markets, but only in one direction in order to eliminate the imbalance of cargo traffic between the markets. In the double-dipping service pattern, a vessel calls at a middle port both ways to combine short-haul and long-haul traffic.

Figure 1.5 Mainline-feeder and mainline-mainline networks

Port positions

Centrality

A port’s centrality position in a vessel transportation network is indicative of the port’s strategic ability in the network to attract port traffic (cargo and passengers) – that is, traffic that passes through the port to and from the port’s hinterland and foreland markets (Hayuth and Fleming 1994). The port hinterland is the port’s landward side and the port foreland is the port’s seaward side. With ports centrally located in their vessel transportation networks, they have greater ability to attract cargo for export and import. “Port centrality represents a port’s ability to attract both cargo traffic from its hinterland area and liner shipping services from its foreland market” (Wang and Cullinane 2016, p. 327).

Origin-destination (O-D) cargo is cargo that is loaded on a vessel at its port-of-origin and is unloaded from the same vessel at its port-of-final-destination. O-D ports arise because of their greater cargo-traffic-generating power (attributed to their centrality-location attributes). O-D cargo moves between two ports – its origin port and its destination port – and it is economical to provide this direct service between the two ports. Such ports have been referred to as hub ports.

Intermediacy

A port’s position in a vessel transportation network has also been described in terms of its intermediacy location. As opposed to direct service, ports may also be involved in transshipment service. At a transshipment port, cargo is unloaded from arriving vessels and then loaded on departing vessels destined for the cargo’s port-o...