Part 1

Introduction

In this introduction, the many facets that make up technical design will be described in an attempt to illustrate a complicated process when seen in isolation. In reality, however, it represents a series of skills that are acquired progressively by most designers in addition to those intuitive skills they are already blessed with.

Technical design in architecture is on one level a process whereby conceptual designs are converted into ‘buildable’ schemes and on the other hand, the design of particular processes that form the foundations on which conceptual design can take place. For example, a completely new conceptual design may require a completely new approach to the design of its individual elements, or alternatively, a new conceptual design may only become possible because of new developments in the design of the individual elements.

Conceptual design can be, and often is, technology driven. However, it is during the detail design stage that the majority of decisions are taken to realise the design vision – a period during which technology is applied to abstract ideas and concepts.

(Emmitt, 2002)

In this section, we will examine how the existing knowledge and skill level of designers will affect the detailed requirements of the process and the actual process itself.

Defining the task

The formal approach to arriving at design solutions starts with a definition of the task at hand. Although it is possible to keep this definition fairly vague in some circumstances, a clear definition does have a distinct role to play in reaching appropriate solutions. Clarity of definition identifies parameters that have a bearing on the particular task. This definition allows unrelated issues to be dismissed and relative degrees of importance to be allocated to the defined parameters.

An example of this process can be simply illustrated by the process of designing a handrail around the edge of a patio. By keeping the definition fairly vague, we can characterise the task as having to prevent people from falling off the edge. With this simple definition, a whole host of possibilities exist, such as:

- increasing the surrounding ground level so that there is no height difference to fall off; or

- ramping the edge of the patio to achieve the same solution; or

- building structures all around so that there is no longer an edge to fall off.

The number of ideas that follow this train of thought are numerous and may result in particularly novel solutions, but many of these are clearly not within the area that would normally be considered satisfactory.

By defining the task in more detail, however, we can for instance give more information on the size and strength required (by referring to appropriate legislation), and this can reduce the number of materials available. By deciding that the handrail should also allow light through, solid walls are also removed from the equation. The defining process then gets down to dictating the style, for instance is a modern design required or would a more traditional approach be more suitable.

To the experienced designer, a number of possible solutions based on precedents begin to formulate in their thinking. These can take the form of ‘safe’ options where precedent suggests that the solution will be acceptable to higher risk ideas where conceptual design skills can be demonstrated. Clear definition will decide whether these choices are possible. It may come down to a decision that only glass is possible, leaving the design decisions down to styling, technical and structural detailing. In other words, what the wall will look like, how will it be constructed and whether it will perform its function?

Controlling the design process

From the above description, we can see that there may be many solutions available and that two teams given the same task may come up with very different solutions depending on their approach. Controlling the process therefore becomes a relevant part of the process and is also directly related to the definition. An experienced designer will have an in-built idea of how much resource should be allocated to a particular task, within a range, allowing time for more innovation or keeping tight schedules with safer solutions.

The creativity of individual designers or the desire to strive for innovation are the forces that drive forward the realisation of design solutions. These are potentially among the most rewarding aspects of technical design but in most cases require careful control. Control of the process also has a major part to play in relation to responsibility. Conceptual responsibility (what will it finally look like?) is a major factor and so is economic responsibility (what will it finally cost?), but in particular, it is responsibility for safety that is paramount (will it perform its task safely and not present a risk to anyone near it?). There are other types as well, such as professional indemnity (PI) (can it be built?).

Dealing with risk

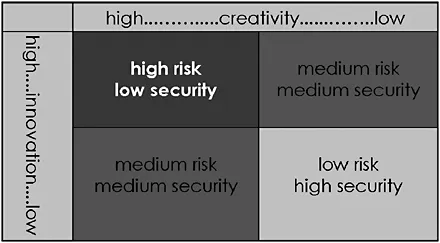

These last couple of paragraphs have highlighted some of the controlling factors in technical design, namely, the relationship with risk. Risk does not only involve issues of safety but includes a possible failure to provide the desired conceptual resolution or to provide a ‘buildable’ solution. There is therefore a relationship between degrees of risk and creativity or innovation and also security.

The relationship with risk in technical design is a variable notion depending on the degree of exposure of the final product. Returning to the example of the handrail above, the risk associated with a highly creative conceptual design can be repaid with recognition from clients, fellow designers, the public, etc., if successful. Whereas, even the most advanced technical solution, if it is not visually distinctive, will not provide the same rewards, therefore reducing the return on potential risk. The fear of failure becomes far more of potent driver in a purely technical design process than in most conceptual design.

The control and mastery of risk is a factor that tends to dictate another major decision required in technical design, whether to attempt a design from first principles or to adapt or adopt an existing solution. In reality, the choice is not so stark but presents itself in choosing in a range between the two extremes. In adopting existing solutions, providing no innovation and thus reducing risk, reputations can be protected and client’s interests possibly best served. Most importantly, however, innovation and creativity can then be channelled in a controlled way to areas where it may see more appropriate returns. These risks and the required control of resources associated with designing from first principles can be controlled by adapting existing solutions to varying degrees.

Nurturing creativity

So far it could appear that there is little opportunity in technical design for creativity and innovation: this is not so. It is, however, valid to suggest that the consequences of failure are far more onerous and potentially fatal than in purely conceptual design. However, careful consideration of the task at hand and precise definition of the design parameters can free the designer from the constraints imposed by a fear of failure and allow truly innovative and creative solutions to emerge. Creativity can therefore be promoted and nurtured by the careful and responsible control of the design process. This process can also be extended to control the exposure of inexperienced designers to unnecessary risks by simplification of and guidance through the process.

Students, equally, can adopt this approach by careful definition and restriction of the project requirements and by consideration of their own ability range before launching into what can be a very daunting prospect for the inexperienced. Technical design therefore follows similar patterns, whether at the advanced levels of modern high-tech architecture or student project levels. The main criterion is to match the nature and complexity of the tasks to what can be handled by the skills of the designers available to complete the task.

The following chapters in Part 1 of this book will examine the stages that go into producing technical design solutions. This includes a look at registering the skills available to a particular project in defining proficiency levels. These skills are not static, they improve constantly with experience, they can be enhanced by study or the buying in of expertise or even by-passed by alternative design strategies. Following on from that, Part 1 then goes on to take a deeper look at the detailed requirements of technical design, delving deeper into the stages involved during the design process, looking at incorporating issues such as sustainability, health and safety and the assessment of success/failure. Part 1 finally concludes with a description of the various choices that go to make up the technical design process. These include choices such as high- or low-tech and aesthetic factors governing materials choice and finishes plus the difficult issue of quality control.

Many technical details are highly dependent on the quality of their production for success, and the designers cannot escape their responsibility to come up with designs that can be constructed within reasonable quality limitations. Keeping control of the overall design process allows degrees of reflection permitting feedback to be integrated into the evolution of new generation responses.

Chapter 1

Proficiency levels: defining the skills available

The ability to design solutions to technical problems depends on the levels of experience, skill and knowledge already in existence. This then relates directly to the amount of resources available for any particular task. Although in theory it is possible for the most inexperienced individual to produce solutions to the most complex of problems, given adequate resources, in practice this is a luxury not generally available. Design solutions tend to come from an existing palette of knowledge with varying degrees of access to the acquisition of more information. Rarely does it come from a totally uninformed approach.

For this reason, expert consultants are frequently used to provide detailed knowledge where a particular shortage is recognised. This process is not without real risks, however, as an over-reliance on ‘expert’ opinion may fail to recognise that this higher level of knowledge may be based largely on current opinion, may be presented as fact and may also be only relatively superior to that already available in-house. Interpreting this type of advice can be difficult and overly dependent on the character of those employed. An example of this would be when an expert fails to see the project as whole but concentrates purely in their own area of skill and also with the added incentive to see their particular solutions adopted.

The tendency therefore to work within existing skills and knowledge ranges results in a reliance on safe solutions, thus avoiding risk but also recognising the higher responsibilities of designers. This last point refers to the professional responsibilities of the designer but also the legal responsibilities imposed by legislation in the UK such as the Construction Design and Management (CDM) regulations.

The scarcity of genuinely independent information is also a real constraint on truly innovative design where the designer takes on full responsibility for its success. How can one designer or even a team of designers manage to become sufficiently expert to fully evaluate all sources of information?

A fundamental element of technical design in architecture is the accurate definition of the skill levels available to the design team but vitally also the gaps in that knowledge.

Palette of skills

The skills that any designer brings to a particular problem will be varied depending on the levels of experience, the types of experience and the individual intuitive and academic skills acq...