This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this book, the author argues and demonstrates that embodiment and relationship are inseparable, both in human existence and in the practice of psychotherapy. It is helpful for psychotherapist, psychoanalyst, counsellor, or other psychopractitioner.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Embodied Relating by Nick Totton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

What is embodiment?

Even as one who encompasses with his mind the mighty ocean includes thereby all the rivulets that run into the ocean; just so, O monks, whoever develops and cultivates mindfulness directed to the body includes thereby all the wholesome states that partake of supreme knowledge.One thing, O monks, if developed and cultivated, leads to a strong sense of urgency; to great benefit; to great security from bondage; to mindfulness and clear comprehension; to the attainment of vision and knowledge; to a pleasant dwelling in this very life; to the realisation of the fruit of knowledge and liberation. What is that one thing? It is mindfulness directed to the body.—Gautama Buddha, Anguttara Nikaya I:21,Thera & Bodhi, 1970

Ineed to warn you right away that it is going to take a little while before there is much direct discussion of therapy in this book. But everything I am going to say before that point is, in my view, required in order to put the necessary ideas in place for us to be able to think usefully about embodied relationship in the therapy room. As you read the next couple of chapters, you will probably find that you are making your own connections with your experience of therapy, both as practitioner and as client; and those connections will, I hope, dovetail with the ones that I gradually begin to make in Chapter Three.

Perhaps the first thing I should say—rather than assuming that, because you are reading the book, we have this as common ground—is that I take embodiment to be central and necessary to our existence, to our being a creature capable of relationship at all. The literary critic Terry Eagleton goes to the heart of the matter: “If something doesn’t involve my body, it doesn’t involve me” (2013, p. 39). Having a sense of embodied relating depends on having a sense of embodiment itself.

The difficulty here is that many of our habitual assumptions about embodiment are shaped by the fundamentally disembodied attitudes embedded in Western culture—the longstanding assumption that “the real me” is mental and/or spiritual. However, there are a number of new ideas available in contemporary thinking which fit better, I think, with our immediate experience of what it is to be an embodied being. Having said that, it is of course much too simple to give total authority to immediate experience: a constant theme of this book is that our experience is shaped by our “knowledge” just as much as knowledge is shaped by experience, so that we tend to experience what we expect to experience. It would be more accurate, therefore, to say that a number of new ideas are giving us the opportunity to change our experience of embodiment!

Paradoxically, many of these new ideas conflict with our “common sense” notions of how things are; hence they may seem at first sight bizarre and hard to grasp. Although common sense generally claims to be experience-based, it filters that experience through thick layers of received opinion and socially respectable dogma to arrive at an acceptable version. Because our direct embodied experience is obscured by so many assumptions—for example, the mind/body split, the subject/object split, the privileging of reason over emotion, the picture of bodies as separated from each other by space like raisins in a pudding, and the belief that causation flows only in one direction—we cannot rely on it to guide us; we need some sort of body centred practice to support us in identifying and staying congruent with what we perceive somatically (and hopefully this practice will not come with too many built-in assumptions of its own). Alongside such a practice, the new ideas I am going to explore provide a scaffolding for a phenomenological—that is, experience-based—reassessment of embodiment. Thus the relationship between experience and theory is entirely dialogical, with each both critiquing and supporting the other.

In order to create a space where we can explore a new interaction of knowledge and experience, I intend to move slowly and carefully, trying to rein in my tendency to leap impatiently ahead. In fact, I need first to take a preparatory detour—actually, two detours, one about the pyramid of rationality and one about mutual causation. Hopefully, the relevance of these discussions will be clear by the time we get to the end of them.

Embodiment and patriarchy

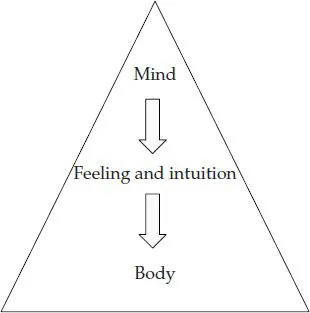

In Western culture, we habitually organise our thinking about embodiment within a hierarchy which is both conceptual and value-based, with mind and rationality at the top, as “‘higher functions”, descending through capacities like feeling and intuition to the lowly body at the bottom of the pile. This descending pyramid is such a fundamental part of our thinking that it is sometimes hard even to notice it in operation; and the privileging of rational thought as “higher” is so intertwined with the privileging of the masculine over the feminine, culture over nature, “civilised” over “uncivilised”, and human over animal that it must be considered an aspect of patriarchal ideology (Rust, 2008; Totton, 2011).

The destructive effects of this mindset on both human and other-than-human worlds are of course enormous (Totton, 2011). For immediate purposes, though, I am going to restrict myself to the destructive effect that it has on our ability to comprehend embodiment, encouraging us as it does to think of our bodies as more or less convenient meat trees where our minds temporarily perch before soaring to greater heights.

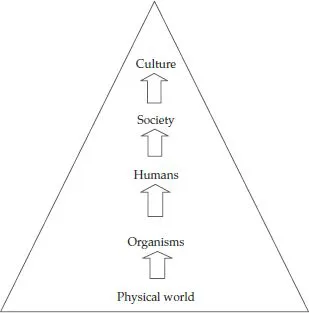

Because of the role that hierarchy plays in the politics of patriarchal societies, we tend to think of it as representing power and privilege. But there are also logical or ecological hierarchies (among others), made up of a series of levels where each is dependent on and develops out of—is in a sense a special part or aspect of—the previous one (Wilden, 1987a, 1987b). For example, there is a pyramid we can imagine with the physical world at the bottom, organisms above it, then human beings, then society, then culture: each “higher” stage defines part of the previous one, and depends on the previous one.

However, the reverse is not true—for instance humans could not exist if organisms didn’t exist, since they are a particular kind of organism, but organisms in general could exist without humans. This is why the arrows point up rather than down, and why a narrowing pyramid is an appropriate image, although if we included all the higher levels we would have something more like a branching tree. To regard the upper, more dependent levels of the pyramid as superior to the lower, more fundamental ones would make no sense; and in fact this hierarchy does not involve power and status, as the patriarchal one does.

The up-hierarchy of embodiment

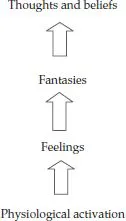

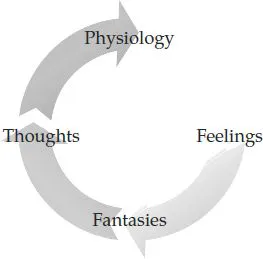

John Heron (1992) has taken a useful and clarifying step in coining the term “up-hierarchy” for a series like this in which the lower elements sequentially shape and determine the upper ones. Heron’s basic up-hierarchy consists of what he suggests are the four fundamental modes of human experience: from the bottom, Affective → Imaginal → Conceptual → Practical. I have adapted this by selecting a different set of moments out of the continuum, starting with the level of our physiology, which most psychologically-oriented systems, including Heron’s, leave out of the picture entirely or treat as a separate substrate.

These four levels represent significant moments in what is really a smooth and continuous shift between what we call the physical and what we call the psychological. Traditionally, Western thought inserts a definitive gap between these two realms—and then puzzles over how to bridge it (Deutsch, 1959). In some ways the difference between the two is simply a matter of what model is most economical for thinking with. We could in principle describe the psyche in terms of atomic interactions, although we would need to know quite a lot more than we do at the moment; but in any case doing so would be unfeasibly longer, clumsier, and more obscure than describing it in terms of thoughts, feelings, memories, attitudes, and so on—a language which has grown up precisely because it is useful for describing psychological events, and is also a description from “inside” rather than from “outside” (see the discussion of smiles at the start of the Introduction). It is mainly the shifts of terminology which give the impression of a series of leaps between levels.

Each of these four levels, like the many other intermediate ones which could also be distinguished, takes up and expresses emergent properties of the one below. As Heron says:

In an up-hierarchy it is not a matter of the higher controlling and ruling the lower, as in a down-hierarchy, but of the higher branching and flowering out of, and bearing the fruit of, the lower.(1992, p. 20)

Hence there is no sense in which the upper levels of the up-hierarchy are “better” than the lower ones; they are simply more specialised and elaborated developments of aspects of the lower levels’ potential. And the image of the psyche “branching and flowering out of, and bearing the fruit of” the body fits very well with the theme of this book, embodied relating as the ground of psychotherapy.

Mutual causation

The up-hierarchy I have illustrated, however, is plainly oversimplified; many levels in many dimensions, and many interpenetrating hierarchies, would be required to come anywhere near an adequate depiction. For example, although in one sense culture clearly emerges from and depends on embodiment—there could be no culture without bodies to create it, while the opposite is not the case (Wilden, 1987, pp. 73ff)—it is undeniable that embodiment is at the same time socially constructed (Evans, 2002; Grosz, 1994; Haraway, 1991), emerging from and depending on culture, which gives particular meaning to the concept and shape to the experience. Equally, our thoughts affect our physiological reactions (“The house is on fire!”) just as our physiology affects our thoughts.

These are examples—and here begins my second detour—of what Gregory Bateson (e.g., 1971) calls “circular causality”, a continuous feedback loop rather than a unidirectional arrow, which is a frequent feature of ecological and other cybernetic systems. Bateson argues that “the organisation of living things depends upon circular and more complex chains of determination” (1980, p. 115). Circular causality is also central to Buddhist thinking, in the form of paticca samuppada, “dependent co-arising” (Macy, 1991a, 1991b); and appears in Hinduism as the Net of Indra, an infinite array of jewels each of which reflects all the others within itself.

From a traditional viewpoint, it looks like a trick or an Escher-like optical illusion for causality to loop back on itself: as with quantum mechanics, “common sense” has not yet caught up with what we understand about reality. However, there are actually many examples of circular (or mutual) causality which are familiar to our ordinary experience. For instance, any feedback-based regulatory mechanism—a thermostat, or even a steering wheel—functions through mutual causation, where a change in the setting produces a change in the output which produces a further change in the setting which produces … and so on. Clearly, where one chooses to locates the “start” of the process—with setting or output, chicken or egg—is arbitrary, and cannot be used to establish a causal arrow of direction. There are also more subtle examples of teleological circular causation, where a goal affects the process.

The term “cybernetics” derives from a Greek root meaning “to steer”, and the science of cybernetics studies mutual causation systems (also known as “autonomous” systems). Our bodies are of course full of systems of this kind, a whole range of physiological thermostats which regulate temperature, heartbeat, and many other vital functions.

Circular causality involves a perpetual and simultaneous bottom-up and top-down rendering of emergence through self-organization, or in Thompson’s [2007] words, both “local-to-global determination (the formation of macrolevel patterns through microlevel interactions) and global-to-local determination (the constraining of microlevel interactions by macrolevel patterns)”.(Witherington, 2011, p. 68, quoting Thompson, 2007, p. 336)

The most immediately relevant aspect of circular or mutual causality for our purposes, however, is its appearance in social and cultural contexts. Ruesch and Bateson give a classic account of this in their book Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry (1951), where they argue that organism—or self—and environment exist only in relation to each other, and that social values, and reality itself, exist as a function of our belief in them as much as vice versa. This corresponds to my statement above that our embodiment both constructs and is constructed by culture.

We will be looking at some aspects of this in much more detail in Chapters Five and Six; however, perhaps a straightforward example would be helpful in showing that we are considering something of concrete significance, not a rarefied piece of metaphysics. A group of Swedish researchers (Gislén, Warrant, Dacke, & Kröger, 2006) investig...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Introduction

- Chapter One What is embodiment?

- Chapter Two Embodiment and environment

- Chapter Three Embodied relating

- Chapter Four Practising embodied relating

- The Story So Far, 1

- Chapter Five Embodied relating in its social context

- Chapter Six Being, having, and becoming bodies

- Chapter Seven Character as embodied relating

- The Story So Far, 2

- Chapter Eight Therapy as play

- Chapter Nine Full and empty speech

- Chapter Ten Embodied trauma and complexity

- The Story So Far, 3

- Chapter Eleven Therapy grounded in embodied relating

- Chapter Twelve Embodied connectedness

- Conclusion

- References

- Index