![]()

1

Children learning through play

Play is the means through which children find stimulation, well being and happiness, and is the means through which they grow physically, intellectually and emotionally. Play is the most important thing for children to do.

(White 2008:7)

This book begins by identifying some of the theories that have shaped the way children in modern-day society are taught across schools and early years settings. It identifies how individual learning styles impact on the experiences children choose and explains how adult intervention can improve opportunities and challenge thinking.

It is widely accepted in modern western society that children will go to school, pre-school, nursery, day care etc in order to learn and socialise, with most parents anticipating that during their time in pre-school and compulsory education, their child will have the best opportunity to become literate and well educated. Over modern times in the United Kingdom, young children and their learning have been under constant review by the British Government. In 2000 the unpopular and formalised Desirable Learning Outcomes were replaced with the Early Learning Goals, and the Foundation Stage for children under five years of age. Various updated documents have led to the now compulsory curriculum used by all settings, the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS). The 2012 revised version of the EYFS upholds the beliefs that children learn best through play and hands-on experiences. This curriculum covers the learning and education of all children until they reach the end of their first year in school, and is widely accepted as the most appropriate form of education for children in their formative years.

This book will be identifying some of the aspects of a developmentally appropriate curriculum, in particular recognising schematic behaviour and identifying how staff can be sure that they are identifying and applying it in their workplace. The book will be looking not only at schemas in children attending pre-school settings but also whether children entering into school show the same schematic behaviour. There will be discussion and studies that identify schemas in children within a reception class and some examples demonstrating how their individual styles of learning can be used to ease transition into the next year group. To make the concept of schematic behaviour relevant and usable there will be advice and guidance about the benefits of understanding and using schemas in order to plan effectively.

In order to fully comprehend why schemas are a valuable tool in the classroom it is necessary to return to some of the theories surrounding how children learn.

From the early twentieth century onwards there has been a major change in people’s attitude to childhood and it is now recognised as a stage in life that is unique. Children are no longer considered small adults, but rather developing adults, children. It is the twentieth century that has been responsible for the majority of today’s thinking about how children learn, with a succession of educationalists and psychologists discussing theories related to learning and development. As childhood became a more established right for all children and law prevented young children from working, there became more of a focus on educating the next generation. Compulsory schooling was introduced for all and the school leaving age has continued to rise, ensuring all children have a reasonable chance of receiving the necessary foundation for adulthood. During this time theorists have published their own ideas about development, education and learning. Some of these have been similar to one another and in some cases build on previous knowledge, others have been more radical and contradictory. But regardless of whether they were right or wrong their work has kept the welfare of children firmly at the core of education and they have helped shape the modern schooling system and the statutory curriculum across the western world.

One of these key theorists was Jerome Bruner who was born in the early twentieth century in the United States of America (USA). Through his work as a psychologist he began to take an interest in finding out how children learnt. He disagreed with the theories Jean Piaget had published, contradicting his concept that children would progress well without adult intervention. Bruner believed that cognitive growth was directly related to the environment and affected by experiential factors. He suggested that intellectual development took place in stages, but that it was directly affected by how the mind was used. His theory highlighted that children should therefore learn in a practical way and that how they learn is considerably more important than what they learn. It was Bruner who first made the phrase ‘spiral curriculum’ commonplace. He recognised that children needed to acquire skills through practice, returning many times to perfect and understand concepts and knowledge. This repetition was of the skills involved in learning rather than the content, with the children becoming more adept and fluent as they retraced stages through their development. Understanding more about schematic learning highlights that children actually do this without prompting or intervention. Practising their skills through a schema is the child’s way of becoming expert in this aspect of their learning.

Figure 1.1 Through repeated opportunities to develop their schema children become experts in their chosen interests (Connection).

Lev Vygotsky was working at the same time in the twentieth century as Bruner, but he took the belief that it was social interaction which was crucial in the role of cognitive development. He suggested that every function in a child’s learning journey needed to take place at least twice. The first time was when an adult or peer interacted and shared their knowledge. The second visit needed to be at an individual level to allow the child to process the information internally. Vygotsky’s second theory was that of the Zone of Proximal Development. This backed up his first theory, that a child would only reach their maximum potential through adult guidance or peer interaction.

Maria Montessori, whilst not making any lasting and significant contribution to the theory associated with the cognitive learning process, has made a noticeable impact on everyday teaching practices. She insisted that the learning environment be prepared, ordered and clean. It should be proportioned to the size of the child and should contain everything he or she needs for learning about the adult world. The space needed to allow for freedom of movement should only contain materials that are conducive to learning. There is a need for people following Montessori’s approach to remember that children are indeed children and that whilst they should be exposed to the real world outside their play experiences, childhood is a phase they need to visit and stay within for some time.

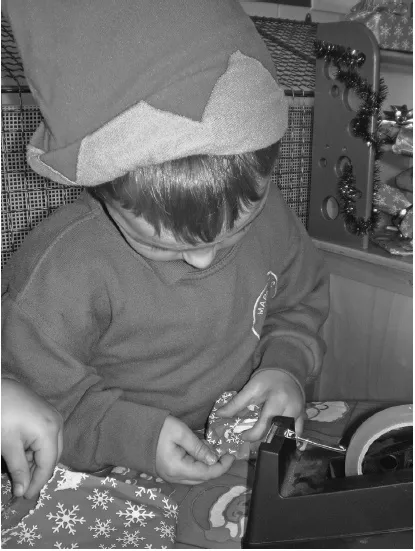

Figure 1.2 Enveloping: following a present wrapping session at home one of the children wanted to continue the activity. Santa’s Workshop was opened to allow children to wrap presents for each other.

There is no reason why knowledge of schematic learning should hinder people taking this approach in their child care setting. In fact it creates an environment that closely resembles the familiar home environments of many children, providing familiarity and comfort. This will give children the confidence to continue exploring and playing across both their home setting and their early years day care environment.

Working in America John Dewey supported Lev Vygotsky’s theory that development of the mind was directly related to the amount and quality of social interaction the child received. With a reputation for being a pragmatist, Dewey suggested that education was not about the facts, but rather the method, skills and experience the children were introduced to. He wanted the education system to develop an approach that celebrated problem solving and critical thinking skills. Whilst his work was not single handedly responsible for a change of attitude in people working with children, it complemented and added to a raft of other available information which has since influenced modern primary curricula. This approach also fits nicely with the theory of schematic behaviours and supports the view that children need to have independent, child-led opportunities to practise and rehearse their thinking.

As we can see over the last century in the UK many of these well-known theorists have also discussed children’s learning habits, identifying in particular how children learn through repeated behaviour. Jean Piaget was one of the first to publish the ideas that most closely resemble schematic behaviour as we now identify it.

During his work with children under the age of five years old Piaget was able to observe and monitor repeated patterns of behaviour. He identified four developmental stages that each child visited in their early years on their way to understanding their world. During the sensorimotor stage babies explore using their senses. The next stage is often known as the pre-operational stage, when children use symbolism to help them develop and they learn to use sound and then words to make meaning and be understood by others. Learning about cause and effect happens during the stage Piaget labelled concrete operations and the final stage, the formal operations, is when children begin to use their existing knowledge to help them to understand further (see Appendix 1). Piaget was an avid believer that in order for children to learn most effectively they had to be active learners, therefore they needed to explore for themselves. It is this theory that is the foundation of modern thinking behind schematic behaviour.

At the beginning of the 1990s it was Chris Athey’s belief that children in the UK were being used in a political debate over the effectiveness of early years education (Athey 1990:9). She was concerned that it was becoming standard practice to assess children’s learning through testing and by producing finished articles of work as evidence of the learning taking place. Athey was adamant that learning and understanding were psychological and pedagogical and that any call for standardising practices and formalising teaching for young children was wrong. This is a view taken by many practitioners today, who are still unhappy about the process of assessing young children formally, in particular once they start their first years of school life. Using the Early Learning Goals as guidelines practitioners are now asked to assess children against extensive learning objectives, allowing the teacher to make accurate statements about the ability of that child at that moment in time. Although there are some practitioners who feel that the assessment is not suitable for all children it is clear that the current assessment will show any cognitive or social problems early on, allowing for intervention to take place if required. The revised EYFS document (2012) has simplified this assessment, allowing practitioners to state whether they feel a child is exceeding, working within or working towards the early learning goals for the end of the foundation year. But despite a call for reduced and unnecessary paperwork, there will still be a requirement for evidence to be collected in order to prove ...