1 About learning

Introduction

Who is this book for?

Why does our CPD need to change?

How can we move on?

Summary

Key points

Many dentists were never taught or shown how to learn.

We need to think less about acquiring information and more about applying what we learn.

Revalidation will require us to demonstrate our learning.

Being able to admit our shortcomings is the first step to self-improvement.

Time spent educating ourselves is as valuable as time spent treating patients.

Most experiences can begin a learning cycle.

Even before we create time, we must protect the time we currently have for reflection.

We can study the changes we have made to our practice to determine how best to learn.

Participating, evaluating and offering feedback all increase the value of educational opportunities.

Introduction

This book is about how dentists can determine their educational needs and address them through the use of ‘personal development plans’. But, surely, we’ve missed out a stage? Don’t we need to establish first of all that there is a need to learn and that dentists are willing and able to engage in the process?

You may feel that such a need is obvious and therefore does not merit further discussion but, as a profession, dentistry is at a crossroads in many ways, not least with regard to how dentists equip themselves for the educational demands of the future. The knowledge, skills and attitudes required for the rest of our professional lives may not be the same as those that many dentists acquired as students and in the early days of practice life.

So it could be with education. Although the demands to analyse our work, show improvements in patient care and root out the ‘bad apples’ in our midst feel like an imposition, it is probably the greatest opportunity we have had to focus our learning on what we think matters. The encouragement to learn from and help each other could lead to a change in culture in which dentists and their teams work together to bring about improvements in service and, just as importantly, in job satisfaction.

Who is this book for?

So much for the rhetoric, but who is this book written for and how can it help you? The personal development plan (PDP) is central to our future continuing professional development (CPD) and in this book we will learn how the plan is written and implemented. We will also look at a variety of techniques that can help us to identify our needs and evaluate our progress.

The text could be read from cover to cover, but is probably better used as a learning resource that can be dipped into and out of according to need and interest. The book is written for generalists by generalists and is intended to be both credible and practical. To prove this point, before reading on, look at the examples of real PDPs on pages 67-79, which capture the spirit of the book.

We anticipate that the book will principally be read by general dental practitioners (GDPs) and it contains numerous

Checkpoints represented by the symbol

with questions and discussion to help readers test their understanding of the concepts involved. To obtain the maximum benefit these questions should be answered before the discussion is read.

The chapter on ‘How to evaluate the PDP’ (Chapter 5) will help dentists to improve the quality of their learning, but will prove particularly helpful to those in the teaching and training community.

Finally, the techniques that this book covers, such as significant event analysis, will gain greater prominence in the near future. The relevant chapters can be referred to when needed and will allow readers to become conversant with the hows as well as the whys of these approaches. These chapters will be particularly helpful if used as background reading material prior to group discussion with other dentists and the dental team.

In the first chapter we consider why our approach to CPD needs to change and how we can begin to achieve this.

Why does our CPD need to change?

When a newly graduated dentist is admitted to the dental register or when a dentist continues to register on an annual basis, there is a requirement that the practitioner keeps up to date with the latest developments in his chosen field, whether it be general or specialist practice. Furthermore and, perhaps, more importantly, there is public expectation that healthcare professions have processes in place to ensure that CPD is carried out and is quality assured.

The GDC (General Dental Council) Lifelong Learning Scheme has now formalised this for the purpose of recertification. The GDC scheme, which is now mandatory, requires dental practitioners to undertake 15 hours of verifiable CPD and another 35 hours of non-verifiable CPD each year during a five-year rolling cycle. In due course, a sample of dental practitioners, taken from a cohort of colleagues qualifying during a particular period, will be subject to scrutiny of their CPD records. If these are found to be deficient, the dentist will be given a period of grace in which to rectify the problem or risk being removed from the register.

Verifiable CPD is fairly easy to record as there is proof through the attendance register. However, non-verifiable CPD (often forgotten) may not appear so easy to log because it embraces aspects of learning and reflection that do not have tangible evidence of ‘attendance’. This non-verifiable element could become the Cinderella of CPD because of the difficulty with producing appropriate evidence. However, it is in this very area that PDPs come into their own as they provide the mechanism to direct our learning to our needs and provide an appropriate record for the GDC scheme.

The GDC is now working on the next stage in the process of ensuring that dental practitioners are ‘fit for purpose’ - that is, competent to continue practising - by moving from recertification to revalidation. Revalidation is intended to ensure that we practise to the highest possible standard and provide the best quality of care for our patients and it will have CPD at its heart.

Of course, at first sight, all this appears to be quite threatening. However, apart from external forces that require the public to be protected (and remember we are all patients too), dentists have the self-motivation to continue to acquire new skills and to further develop themselves and their teams.

There is clearly then no better time to be innovative in the way we think about personal development. We need to move away from the philosophy of the perceived need (i.e. attending educational events that appear to support the things we like doing and to which many of us often go) and towards finding learning events that it our personal ‘needs assessment’. Clinical audit and peer review in the General Dental Service (GDS) are now a Terms of Conditions and Service requirement; in addition, it is likely that GDPs will be required to undergo some form of appraisal similar to that which hospital consultant colleagues are already undertaking.

Each of these forces - revalidation, appraisal and self-directed learning -will centre on the PDP and hence learning how to produce and implement one is both valuable and necessary.

How can we move on?

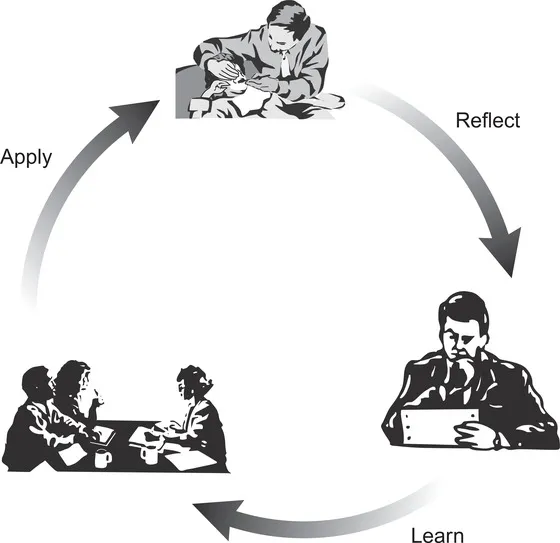

We have seen why our CPD needs to change. In this section we will first look at a model of how we learn, called the learning cycle, then use this as the basis from which to consider how improvements in our learning can take place.

The learning cycle (after Kolb)

This model demonstrates how experiences lead to a cycle of reflection and change which result in learning, as illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The learning cycle.

The dentist becomes aware that his inferior dental block is not working well, an experience which makes him uneasy and prompts him to reflect as to why this might be. This sense of unease alerts him to the fact that a gap exists between what he needs to know and what he actually knows. He realises that the cause of his discomfort is his lack of confidence about how best to give the injection and what to do when this fails. He therefore defines his educational need as learning how to improve his injection technique and learning a back-up technique that he can use when the block fails.

In order to learn, he has to identify not only what he needs to learn but also how he wishes to address that need, and on the basis of this he decides to do a literature search to identify best practice and to discuss the problem in a peer-review group. He finds that he is not alone in having difficulties but discovers that he can improve his technique by directing the barrel of the syringe towards the contralateral upper pre-molars, rather than the lower pre-molars. He also learns the intraligamentary injection technique to use as a back-up.

Having improved his skills, he is now able to apply his learning so that the next time he has to give the block, he feels good because he has more confidence in getting it right first time and he knows what to do if this fails.

Figure 1.1 indicates that thinking about such experiences, putting them into context and considering their implications (the process of reflecting) allows us to learn from them and decide whether changes are needed. Changes are not always welcomed, but if they are regarded as improvements that we wish to make, then they are more likely to be put into effect.

We will now look more closely at three elements in the learning cycle: experience, reflection and learning.

Using our experiences effectively

The first thing to recognise is that experiences are the raw material from which we define our learning needs. All experiences have this potential, even the seemingly trivial ones, and they are derived from:

what we do - through assessing patients, carrying out procedures, etc.

what we become aware of - through reading, feedback, complaints, audit and analysis of data, etc.

what we feel - for example, in response to signficant events in our practice lives.

Although we could learn from all experiences, in reality some ex...