- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Systems Thinking for Harassed Managers

About this book

This book describes the processes that shape organisational life and shows how managers can work together to help one another to work out their problems and develop their skills. The authors draw on their experiences of working with managers and in the group relations field.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Going round in circles

Technical or formal rationality is linear: you reason, you act, you achieve accordingly. Encompassing reason is circular and iterative. You probe, discover something interesting, reflect, cogitate and probe again. The manager acts with whatever degree of forethought is appropriate, but carefully examines the feedback and, through a cybernetic process, rethinks and acts again, learning along the way.

C. Hampden-Turner, 1990, p. 5

Over the past nine years we have run a series of workshops in which managers have consulted each other about problem situations in their organizations. We have also acted as consultants to managers in a range of organizations, and have consulted each other and other people about our own work. This has given us a picture of the kind of circumstances in which managers and others become sufficiently perplexed or exasperated to seek an outsider's perspective on what is going on around them.

The problems themselves have been varied and complex. Many have reflected larger-scale pressures on the life and governance of organizations in Britain: pressures towards greater efficiency and value for money, flatter organizations, equality for disadvantaged groups, clearer accountability on the part of those who spend public and charitable money, and a sharper focus on the quality of provision for customers, clients, and service-users.

We have worked with directors, senior managers, and governing bodies directly concerned with formulating policies in these areas, but much of our time has been spent with the managers who have had to implement such policies. Many of these have identified themselves strongly with the harassed managers in the title of our workshops and of this book.

Some have been concerned with how to generate a sense of ownership of policies that are felt to have been imposed from above; how to implement policies for which—as they see it—there is limited support or even active opposition; how to enable people to keep their wits through what seems like continuous organizational and social change; and, in extremis, how to deal with angry and cynical staff.

Others have raised difficulties that were on the face of it more local: how to make a functioning team out of a collection of people who had stronger professional or ethnic allegiances elsewhere, or who did not see themselves as a team or were at daggers drawn; how to secure the co-operation of wayward or difficult team members; how to get voluntary workers or committee members to conform to the standards of practice desired by their salaried senior managers and perhaps by funding bodies; how to wind a unit down, or to set up a new one from scratch or by merging previously existing units with distinct histories and cultures; how to preserve continuity while key figures leave and new brooms sweep in.

What do these disparate problems have in common? We have become aware of these recurring themes:

- Stuckness: managers are faced with a state of affairs that they cannot accept, but which they are unable to shift. Whatever solutions they have tried have not worked, or are not working fast enough. Their bosses cannot help, or cannot be approached, or are part of the problem. They are going round in circles.

- Politics: many problems, as they are defined, hinge upon the manager's power, or lack of it, to influence other people to do what he or she believes is necessary. Sometimes the manager has formal authority but is uncertain how to exercise it; sometimes he or she is entirely dependent on the willing co-operation of others.

- Complexity: the situations described are invariably complex, both to grasp and to analyse. To understand what lies behind even a simple question like "How can I enable the staff to talk to one another and trust one another?" entails exploring a complex and ambiguous domain. It is necessary to take in a lot of information. It is also necessary to grasp what has been called the dynamic complexity (Senge, 1990, p. 71) of the underlying situation (this is discussed further in chapter two).

We have found that we, and the managers we work with, are able to gain leverage on the problems they present—to engage with them in a way that addresses the manager's stuckness, the politics, and the situation's dynamic complexity—if we examine what is going on from the perspective of systems thinking. This book is a demonstration of what we mean by adopting a systems perspective, and later in this chapter we explain what we mean by this. But first, here are accounts of two incidents, from our own experience, which may begin to give you a feel of systems thinking in practice.

A "Difficult" Individual

Clive, the manager of a small research and development team in an impoverished social services department, was exasperated by a competent but uncooperative and evasive member of his team. She ignored the team's priority work in favour of projects of her own and was frequently out of the office and uncontactable. Nothing he had said in her supervision sessions had made any difference. The rest of the team were becoming resentful and demoralized.

Clive regarded his unit as a spearhead for change within the department. New legislation meant that big operational changes were in the offing, to which the director was strongly committed (though other managers were less enthusiastic). Clive's deadlines would have been tight even if all his team had been pulling their weight.

He consulted a group of participants on one of our workshops. They suggested that this was a normal state of affairs. They asked him more about the ambivalence about change in the department. It appeared that, while he was committed to change, others were putting the brake on. The group suggested that one way of reading this was that they were preventing the department from moving too fast. His uncooperative team member might be representative of a sizeable body of people who wanted to hold on to what was tried and familiar in their way of working.

The group went on to suggest a number of options for action, some of them mutually exclusive. One member suggested finding the difficult team member another job, another that Clive should start disciplinary proceedings. Another proposed that he should stop putting pressure on her and start to behave in a way that acknowledged her contribution to the work of the department as a valid and useful one.

The latter is what he in fact did. He redefined her job within the team, so that she could continue the kind of work she was familiar with and good at, and arranged for her to consult another assistant director about the deadlines she should work to—someone who would take the heat off her, because he was less anxious about the forthcoming changes than he was himself. In a short time she became a much more positive member of the team and even began to give some time to the research and development priorities.

What is going on here? It is significant to us that in discussion Clive begins to adopt a wider perspective on what initially seemed to be trouble with an uncooperative individual. To move or discipline (or sack) a "difficult" individual, as some people suggested, often seems the only solution and conforms to the popular image of the tough manager. But this would have left unaddressed the larger process of which this behaviour was a part: the department was torn between adapting to new circumstances and holding on to a sense of continuity and to what was good in the old way of doing things. Of course it might be suggested here that the manager caved in and accepted that he had one less person on the priority work. So his change of behaviour towards the team member may not have been wise, unless he had also had some tough conversations with his director about a pace of change that the department could sustain. This is an important element in systems thinking: that a change in one relationship within a system changes all the other relations too.

When is a Team not a Team?

Here is another example. A psychotherapist contacted one of us (BP) on behalf of a multi-disciplinary child guidance team based in a hospital. The team comprised psychotherapists, consultant psychiatrists, a social worker, an occupational therapist, a psychologist, and two administrators. They were having difficulty working together as a team and had obtained funding for an "awayday" in which to try to sort out their differences with a consultant.

The consultant had difficulty agreeing with them about achievable goals for the day, not least because every time he wrote or telephoned he found himself dealing with a different person. He asked every team member to write him a letter explaining what they saw their difficulties to be. When he had read them he wondered what on earth they could do about it all in a few hours.

On the day, he asked them for examples of what they regarded as teams. They said a football team, or the team in an operating theatre. He pointed out all the ways in which they were not like these teams: there was no goal that they were all shooting at; they worked with their clients only singly or in pairs, never all together; they were in different professions with different values and conventions; they had different bosses, different pay and conditions; one member, the social worker, was in a different organization from the rest of them. He asked why they didn't forget about being a team and regard themselves simply as colleagues who met periodically to discuss and co-ordinate their work with children.

Through the day the mood shifted. They had seen themselves as failures, unable to live up to their ideal of teamliness. Now they began to see themselves as achieving a modest but useful level of collaboration in the face of massive obstacles. What is more, they were working together very effectively at that moment, listening to each other, making inventive suggestions, ignoring differences of status. Before they went home, they had made various undertakings to each other about how they would modify their behaviour to strengthen their cohesion as a working group. In a letter to the consultant a year later, one of the psychotherapists said:

We have started to put into practice some of the suggestions made, and have a special meeting now to raise difficult issues each week. I managed to arrange to see one less client so that I also have more time for meeting colleagues! Management are undoubtedly nervous about our newly strengthened cohesiveness, but it is clearly up to us to help them understand.

So there is a group of co-workers who create a new space for themselves—the "awayday", away from the hospital—in which a different pattern of working together can emerge. There is someone who sets out to help and gets entangled in their problems himself. There is an unexpected move, by which he gives them reasons for despairing of working together, rather than trying to give them hope. And there is a modest change, which leaves many problems unaddressed and disturbs another part of the system, but which is enough to set them on a new course.

Systems Thinking

What, then, is meant by the word "system"? A system is a set of components that make up a complex whole—a whole that is more than the sum of its parts. This is a general definition, for all kinds of system. The human body may be looked upon as a system, one whose components are its constituent cells. The body is more than an aggregate of cells: its qualities and capabilities could not be deduced from the properties of cells. Similarly the relations between the flora and fauna of a region can be better understood if they are seen as components of an eco-system. (In all these statements we have used phrases like "may be looked upon", "may be understood", because systems, like beauty, exist in the eye of the beholder. No system exists without someone who perceives or distinguishes the components as components of a larger whole.)

In the world of human associations like Marks and Spencer, the Beatles, The Children's Society, the Berlin Philharmonic, Dorset County Council, and our own teams and families, organization theorists have distinguished systems with various kinds of components: individuals and work units of various sizes, and also recurring behaviours or activities, sometimes conceptualized as roles. It is with this last type of system—systems as patterns of interaction— that we are primarily concerned. This strand of systemic thinking originated in the work of Gregory Bateson (1972) and has been influenced by the Milan school of family therapy (e.g. Selvini-Palazzoli, Boscolo, Cecchin, & Prata, 1980). From this point of view, a system is a pattern of interaction, between persons or groups, which can be represented by one or more feedback loops—that is, by closed loops or sequences of interaction that link and integrate all the components of the system. We say more about this concept in the next section.

So systems thinking is a way of describing and explaining the patterns of behaviour that we encounter in the life of organizations: the regularities of individual behaviour, which we describe as a role, the characteristic ways of doing things in organizations which we refer to as their culture, the repeating patterns of sterile conflict or mistakes or absenteeism or failure to delegate, which we define as problems and try to solve.

Once we have constructed models of the feedback processes that generate the behaviour we regard as problematic, we can use them to explain why our attempted solutions have failed to shift the problem, or have even perpetuated it, and to suggest other strategies that might have more leverage. Whether or not implementation of these strategies has the results we hoped for, it gives us more information about the system, so that we are able to construct new or modified models that explain more of what is going on. It is this process of observation, model-building (hypothesizing), and intervention that we shall be describing in this book.

Linear and Circular Processes

In order to understand the concept of systems as closed feedback loops, it is necessary to distinguish between linear and circular (or recursive) interactive processes. A few examples will demonstrate the difference. A woman is sitting with a cat on her lap; she is stroking the cat, and the cat is purring. The woman thinks: "The cat is purring because I am stroking him." This is a linear description: an effect (purring) is explained by means of a cause (stroking). The description is of the general form shown in Diagram 1.

Diagram 1

The cat has another view about it. He thinks: "The woman is stroking me because I am purring"—another linear explanation, but with a different view of cause and effect (Diagram 2).

Diagram 2

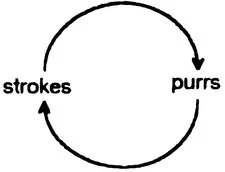

But it is possible for us to take a third view, from outside the system, arid propose that each behaviour triggers the other, in a continuous process of circular causation (Diagram 3).

Diagram 3

One of the foremost authorities on circular causation is Hawkeye, one of the maverick doctors in the M*A*S*H television series. On one occasion Hawkeye and the Colonel are ambushed by the Chinese. The Colonel starts shooting back, but Hawkeye holds fire. When the Colonel asks him why he is not returning their fire, Hawkeye replies:

The reason they shoot is because they're angry. If I shoot at them they'll get even more angry and shoot at us.

On another occasion Hawkeye and the Colonel have been helping out at an overworked South Korean field hospital. As they are leaving, the hospital chief speaks to them:

Chief: Thank you for all your help.

Hawkeye: Thank you for all your wounde...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Contents

- EDITORS' FOREWORD

- FOREWORD

- FOREWORD

- Introduction

- CHAPTER ONE Going round in circles

- CHAPTER TWO What's the problem?

- CHAPTER THREE Asking the right questions

- CHAPTER FOUR Constructing hypotheses

- CHAPTER FIVE Finding a new course

- CHAPTER SIX Theoretical postscript

- APPENDIX How we introduce course participants to systems practice

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Systems Thinking for Harassed Managers by Nano McCaughan,Barry Palmer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.